Taxes are the topic of the year.

The focus is mainly on taxing “the rich,” because both Republicans and Democrats agree that levies on low- and middle-income taxpayers should not be increased.

Changing the tax system comes under the label of tax reform, an ongoing attempt to make the system fairer. The system is now based on taxing people with higher incomes at a higher rate – called “progressive taxation.” The issue is all about how much wealthier people should pay.

The tax reform debate today has three key elements:

● What the tax rates are

● What counts as income for tax purposes

● What is the income level where the top rate clicks in

WHAT MAINE DID TO CUT TAXES AND SPENDING

Take Maine, for example. This year, Gov. Paul LePage and the legislature agreed that, beginning in 2013, the top tax rate will be cut from 8.5 percent to 7.95 percent. This rate will apply to a married couple’s taxable income of $39,900 and above, adjusted for inflation. And what is defined as taxable income will be more closely aligned with federal tax law.

Does this mean that taxes will be cut for the wealthy? Yes and no. While the wealthy have incomes well above the amount where this top rate will apply, so do a great many middle-income people. In 2009, half of Maine families had incomes above $47,502.

Compare that with the Maine income tax in 1969, its first year. The top rate was 6 percent and it applied to incomes over $50,000. That would be the same as $308,000 today. Clearly, the top rate was originally intended to affect only the wealthy.

The net result of Maine’s tax reform, which includes several other changes, will be a $150 million reduction in the amount raised by the income tax. Because state government must by law have a balanced budget, that means there must be matching cuts in state spending.

Maine’s top income tax rate is among the highest in the country. Both Republicans and Democrats have been seeking to lower it, and the new tax law moves in that direction.

U.S. DEFICIT DEBATE: CUTTING SPENDING, RAISING TAXES OR BOTH?

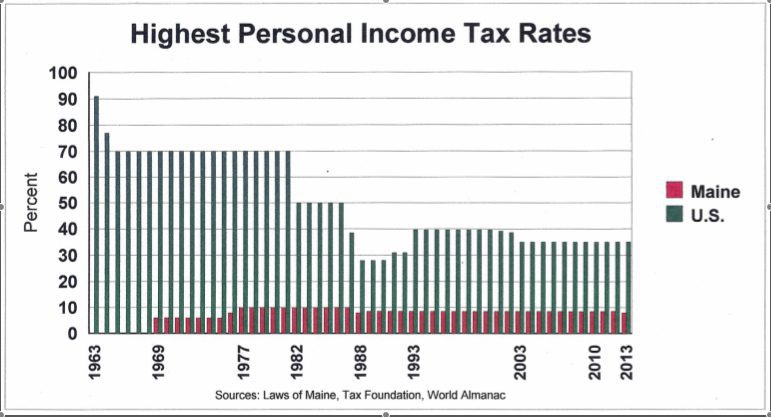

The situation is different in Washington. The top tax rate is lower than it has been in many years. From World War II through 1963, the rate was as high as 91 percent. It gradually came down to 28 percent in 1988. It is now 35 percent, set in 2003.

Top federal personal income tax rates declined over time. After hitting 28 percent, they rose when new loopholes were added. Maine rates started at 6 percent; now 8.5 percent, they are slated to decline to 7.95 percent in 2013.

To help reduce the expected shortfall in federal revenues, President Barack Obama proposed increasing taxes on the wealthy by adding 3.5 percentage points on income above $250,000. That would bring taxes back to the level in the 1990s. Republicans objected, preferring to reduce the deficit by using spending cuts alone.

Obama gave up on raising the rate on the highest incomes. Instead, he proposed reducing or eliminating some tax breaks – officially known as “tax expenditures,” but often simply called loopholes – that benefit the wealthiest people and oil companies. That would not change the top rate but would increase what counted as income for the most wealthy.

That’s what happened in 1988 when rates were at their lowest. When rates were cut, many tax breaks were eliminated. When Congress started to put some back into the tax law, rates were raised. Then, the 2003 tax law cut the rates without reducing tax breaks.

Some Republicans say they would accept cuts in some tax breaks if rates were also lowered. They say that any tax reform must either produce no change in federal revenues – making it “revenue neutral” – or it must produce a tax cut to be paid for by more spending cuts.

Most Democrats insist that the result of tax reform must be an increase in money raised from the wealthy, notably investment chiefs who have recently earned big bonuses. Along with spending cuts, this money would be used to reduce the deficit.

When the deficit deal is complete, both spending and taxes will be part of the package, because both parties include both pieces in their proposals. Given the projected trillion dollar deficits ahead, major changes are inevitable.

Taxes are the fuel of government. If you believe that government should be reduced, cutting taxes not only affects citizens as taxpayers but also as consumers of government services, who must accept less. If you believe that many government services are essential, then cutting taxes is not desirable.

Thus, to a considerable degree what is really at stake is not only tax reform but competing views on the role of government.