Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

If you’ve ever taken the Amtrak between New England and New York, you may have noticed a lot of power plants — or facilities that resemble power plants. It can be hard to differentiate all those big smokestack-topped buildings flashing by in the Northeast corridor. Nuclear? Gas? A shuttered coal plant? Who owns them? Are they running now?

I’ll often pull up Google Maps on my phone and squint at the satellite view, trying to pinpoint what I just saw. I could try using a public resource like this map from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, but I’d still need to do some sleuthing to learn about ownership and operations — and I only have a vague sense of how to do this because I make a living as an energy journalist. Even then, the data I can typically access tends to be months or years old.

These are facilities we pay to use every month, that keep our lights on, that can be major sources of planet-warming greenhouse gases and air pollution. I think it’s fair to say that it seems much harder than it should be to know where these plants are and what they’re up to.

During the winter storm that began just before Christmas, a few weeks ago, some unknown number of power plants in New England were not there when we needed them. ISO-New England, the entity that oversees the region’s power grid, declared what’s known as a capacity deficiency around 4:30 p.m. on Christmas Eve, after about 2,150 megawatts “of resources scheduled to contribute power during the evening peak became unavailable.”

ISO called on resources that could spool up quickly — primarily oil plants — to get online and fill the gap. The issue was resolved without requiring conservation measures or rolling blackouts.

This month, ISO announced that the delinquent generators will be fined roughly $39 million “for failing to meet their obligation during the capacity scarcity conditions,” and generators that “over-performed” during the deficiency will get a proportional bonus.

But the ISO is not saying which generators messed up on Christmas Eve, or which were called upon to make up the loss.

“The ISO New England information policy is intended to prevent the release of market participant confidential information, especially if that information could be used as an advantage by a competitor,” ISO spokesperson Ellen Foley said in an email. “As a result, the ISO doesn’t release information about the operating or financial status of a generating resource. … Charges for underperformance are paid by the underperforming resources, not electricity ratepayers.”

It’s true that consumers will be mostly shielded from the high prices caused by the deficiency, and the resulting fines. Our energy bills are made up of much more than just generation costs, and most of the electrons are bought, sold and priced well in advance of any given afternoon.

But there are other reasons to be interested in this mystery. For one thing, 2,150 MW is a lot of power — about 12% of the peak demand of 17,500 MW forecast for all of New England that night. Put another way, it’s roughly the capacity of Millstone Nuclear Power Plant in Connecticut (which you pass by on the Amtrak to New York). Millstone’s two reactors, and the one at Seabrook Station in New Hampshire, often supply at least a quarter of the region’s electricity.

Then there’s the question of emissions. The ISO says it used mostly oil reserves to address the capacity deficiency on Christmas Eve. Wyman Station in Yarmouth was one plant that was spotted steaming away that afternoon — more here from the AP’s David Sharp and Portland Press Herald’s Tux Turkel — but we wouldn’t have known it ran if we hadn’t been looking.

Federal data on fuel use and emissions at the level of individual power plants is available on a monthly basis, with a two-month lag. So we’ll know a little more soon about what the fuel mix looked like in December 2022 — but we still won’t be able to zoom all the way into Dec. 24. It’s also expected that federal investigations into Christmas Eve energy issues — not just in New England, but nationwide — are forthcoming. But we don’t know what details those might reveal.

The lack of transparency around the Christmas Eve episode has been a hot topic among the region’s energy wonks in recent days. Joe LaRusso, a frequent contributor to #energytwitter, has had some excellent threads on the topic.

“Extreme weather events like Winter Storm Elliott [the late Dec. 2022 storm] reveal the weak links in any system,” he wrote. “How can the public be assured those vulnerabilities have been addressed if ISO-NE won’t identify the plants that failed?”

Ari Peskoe, the director of the Harvard Electricity Law Initiative, questioned what advantage a competitor could gain from knowing how a certain generator performed at a certain hour weeks prior. Moreover, he said transparency should be a “bedrock principle” as the ISO works with stakeholders to plan a more modern grid that can meet the challenges of climate change.

“As we look to change policies, whether it’s for decarbonization, for affordability, for reliability, we should have all the information to make informed choices,” Peskoe told me this week. “One of the major issues that keeps popping up in New England, year after year after year, is this sort of winter reliability issue — and so this seems to be relevant to those discussions.”

Remember the record New England cold snap in January 2018, where temperatures barely cracked single digits for close to two weeks? This was a benchmark episode that grid managers still recall when talking about winter reliability concerns. Another benchmark was the Texas grid’s deep freeze, which LaRusso notes was foreshadowed by similar outages a decade prior.

Back in January 2018, the big worry here was gas supplies — frozen harbors and rising use of gas for home heating meant less available for power plants to burn, meaning ISO-NE had to lean heavily on dwindling oil reserves. We still don’t know exactly what happened this past Christmas Eve, but the ISO says it wasn’t a fuel supply problem, contrary to some reports.

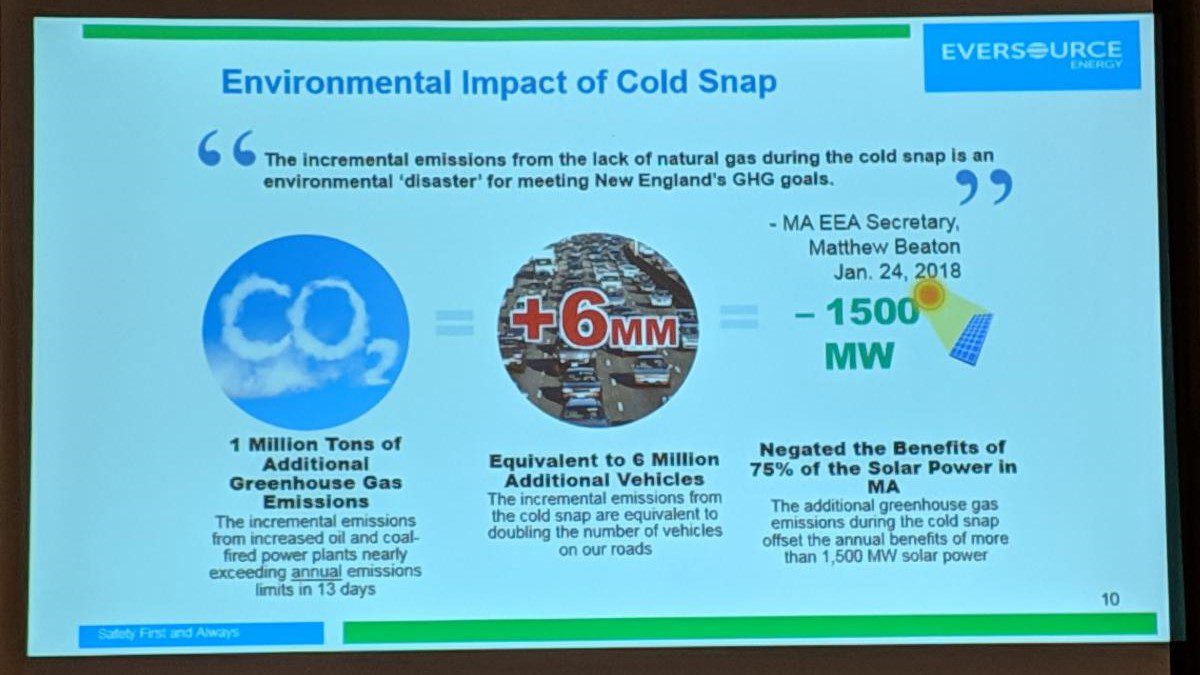

Close to a year after the 2018 cold snap, I went to an energy conference in Manchester, N.H., put on by a trade group of factories that often lobbies against renewable energy policies in the name of keeping rates low. Someone from Eversource, the big electric utility in New Hampshire and other parts of New England, gave a presentation in a hotel ballroom that included this slide:

This is the claim that’s stuck with me: The emissions from the oil the New England grid burned to get through the 2018 cold snap were enough to cancel out most of the solar power installed in Massachusetts at the time.

Analysis by E&E News found the region got more of its electricity from oil this past Christmas Eve, at 29% of the fuel mix, than on any day since January 2018. Episodes like this don’t happen in vacuum — they have real implications for New England’s climate efforts. The more details we can access about how our grid works in these moments, the better we may be able to adapt.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: A Christmas Eve mystery on the New England electric grid.

Reach Annie Ropeik with story ideas at: moc.l1764359406iamg@1764359406kiepo1764359406ra1764359406.