Sometimes there are no words to take away her son’s pain.

So Marie wraps her arms around her child and cries with him.

A few times a week, the 11-year-old breaks down, overwhelmed with the adversity he faces as a transgender boy. His peers, his mother said, have called him gross, stupid and a pervert.

The Penobscot County fifth-grader also suffers from gender dysphoria, a psychological condition that causes distress for those whose gender identity does not match their birth-assigned sex.

He despises the feminine body he sees when he looks in the mirror. He has pulled his hair out, cut himself and banged his head against the wall.

“It’s heartbreaking,” his mother said. “I validate him as much as I can, so that he knows at the end of the day that it’s not about him. He is not what’s wrong.”

A study recently released by the Williams Institute at UCLA estimated there were 5,900 adults 18 and older in Maine and 1,200 children aged 13-17 who identified as transgender.

The state’s transgender adolescents, according to the 2019 Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey, were twice as likely to have been bullied at school and four times as likely to have been threatened or injured with a weapon. Half of them had considered suicide compared to 15 percent of their non-transgender peers.

“It can be really scary and isolating coming out,” said Aiden Campbell, a transgender male who works at OUT Maine, an LBGTQ advocacy organization.

Living as a transgender youth in a largely rural state can be especially difficult. Medical and mental health resources are hard to come by, and growing up as a trans kid in a small town or school can be lonely and heartbreaking.

“They may be the only one coming out in their school or town,” said Campbell, who endured bullying before he transitioned and became the sole transgender student at Cony High in Augusta.

Campbell tried to end his life in 2012, believing he would never be loved or accepted.

“I know what it feels like to be in a dark place and feel really lonely,” he said. “But kids shouldn’t think suicide is the answer they have to turn to because they don’t feel accepted.”

RELATED: One transgender man’s journey to find hope and happiness

Along with the struggle to fit in at school, at home or in their community, Maine transgender youths and their families are reeling from the heavy number of political attacks nationally.

More than 100 bills targeting transgender people have been proposed in other state legislatures since 2020, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. The bills include banning transgender students from playing girls’ or women’s sports, using bathrooms that match their gender identity and criminalizing gender-affirming treatment for children.

Maine’s legislature has defeated proposed anti-trans laws in recent years, but the state’s Republican party amended its platform during its April convention to call for a ban on discussing transgender identity in schools. Former Republican Gov. Paul LePage, who is running for re-election, has supported laws restricting transgender rights.

Though Democratic Gov. Janet Mills has a history of voting for LBGTQ rights, advocates recently criticized her for removing a teacher-made video from the Maine Department of Education’s website that discussed gender identity and same-sex relationships and was intended for kindergarten students. After the video was used in a Republican attack ad, Mills and the DOE eliminated it from the state website, saying the lesson plan was not age-appropriate for kindergartners.

The push to ban discussions about LBGTQ students in the classroom and to restrict their rights and medical treatment, frightens Marie, who is being identified by her middle name to protect her son’s privacy.

“I have a lot of feelings and fears about these laws,” she said. “To not get my son treatment is criminal. There is substantially higher risk of him committing suicide if he doesn’t get help. And I will do anything I can to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

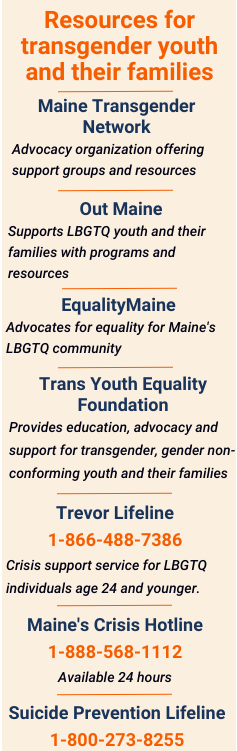

When parents like Marie seek resources for their children, they often turn to advocacy groups like Maine Transgender Network or OUT Maine, which offer online support groups, workshops and links to medical and mental health professionals.

Medical care is typically provided at the state’s two pediatric gender clinics, in Portland and Bangor. The Gender Clinic at Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital at Maine Medical Center opened in 2015 because of a growing need to treat adolescents who had to travel out of state for services. The clinic has 1,000 patients ranging in age from 3 to 25 from Maine and New Hampshire, said the clinic program manager, Brandy Brown.

While most of the patients are between ages 14 and 19, there are some who are pre-kindergarten or in grade school.

“With most of our young patients, the parents have a lot of questions,” Brown said. “They’re here for support and guidance.”

Younger pre-teen patients, Brown said, are generally exploring their gender with social transitions such as wearing clothes that may not align with their birth-assigned sex. Sometimes they also choose to rename themselves.

CLICK HERE TO SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THIS STORY

In the third grade, Marie’s son began altering his appearance to diminish his female characteristics.

“He had these long waist-length curls and he shaved one side,” Marie said. “And then he slowly worked up (his head) until all of the sides were shaved and he just had a bit of hair on top.”

At age 9, he told his mother, “I think I’m a boy.”

The dark-haired, sensitive child did not waver in his chosen identity, Marie said. He changed his name and appearance in the spring of 2020 when his school went to remote learning during the pandemic. When he began attending a new school in the fourth grade in the fall, he dressed in baggy pants and shirts. His classmates, his mother said, accepted him as a boy.

“Most of the kids in the class were new to him,” said Marie. “At that time the transition was pretty easy.”

But a few students who knew him before began teasing him, Marie said. Others in the class also taunted him after her son explained, “I was born a girl but now I’m a boy.”

“It was a constant barrage,” Marie said. “He’s got a shaky self-esteem so if he is having a bad day, he’s taking it out on himself.”

His emotions, Marie said, pour out in a stream of self-hate.

“I’m ugly,” he tells his mother. “I’m fat. I’m stupid. I’m not good enough. Nobody loves me. I wish I was dead.”

He also continued to hurt himself, Marie said, cutting and scratching his arms until he left scars.

Marie sought help for her son at Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center Gender Clinic in Bangor, which opened in 2017 and currently has 200 patients. The clinic’s psychologist and endocrinologist — a doctor who specializes in the body’s glands and the hormones they make — evaluated Marie’s 11-year-old child and determined he had gender dysphoria.

While not all clinic patients receive medical treatment, doctors prescribed puberty blockers for Marie’s son, she said, to ease his distress. The medication suppresses hormones that would cause changes like breast development and menstruation.

“He is very conscious of how his body looks and cries at the sight of it,” Marie said. “He wears these oversized T-shirts and loose baggy clothing to try and hide it. We were fortunate that he could start treatment before his puberty progressed.”

Puberty blockers, explained Dr. Mahmuda Ahmed, the Bangor clinic’s lead pediatric endocrinologist, delay puberty and give children time to see if their gender identity is long lasting. The medication, Ahmed added, is also given to non-transgender youth experiencing early or “precocious” puberty.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health supports the use of puberty blockers, and the country’s top medical associations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association, also endorse some forms of treatment for transgender youth.

When it comes to puberty blockers, though, critics argue more research is needed to understand the medication’s effect on a patient’s fertility and bone density.

Once the blockers are stopped, an adolescent’s body begins to produce hormones again. Pausing the production of estrogen and testosterone hormones provides relief to children whose biological bodies do not align with their gender identity, said Dr. Anna Mayo, a psychologist who evaluates patients at the Bangor clinic.

“All of a sudden your body is changing in ways that don’t match your identity and that can be a really distressing time in a child’s life,” said Mayo.

When a transgender child does not receive treatment and undergoes puberty that conflicts with their identity, the results can be dire, said Susan Maasch, director of Trans Youth Equality Foundation, a Portland-based nonprofit that provides education and support for transgender youth and their families.

“Kids begin to give up hope,” Maasch said. “They become destructive, do badly in school. Inevitably they fall into a deep dark place and need mental health services, or worse and they take their own life.”

Gender-affirming care for adolescents is controversial in many states, and conservative groups like the Christian Civic League of Maine assert that such medical treatment harms youth. But Ahmed points to several studies, including a recent report published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, which found treatment of patients with forms of gender dysphoria lowered moderate or severe depression and decreased suicidal thoughts and attempts.

Often, doctors say, families have questions about medical research on transgender youth and are hesitant to seek treatment that will change their child’s appearance. Sometimes children alternate between divorced parents who disagree on care or social transitioning a child with clothing and name changes.

“The kids are stuck in the middle suffering,” said Maasch. “I have one child now where the mother accepts her (as a transgender girl) and the dad doesn’t. Besides suffering depression, a kid who shows up to school one day dressed as a boy and then later dressed as a girl is more vulnerable and more likely to be harassed.”

Maine and most states do not have laws governing transgender pediatric care. Maine’s gender clinics follow the World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines. Depending on what provider they see, a youth can receive puberty blockers with only one parent’s consent. But surgery to alter a child’s body or hormone replacement therapy — which can feminize or masculinize an adolescent’s secondary sexual characteristics like facial hair and breast formation — requires both parents’ permission.

In recent years, gender-affirming care for adolescents has become a controversial issue. As of March, according to the Williams Institute, 15 states have restricted access to treatment or are proposing laws to do so. Some of the bills criminalize medical care, and impose penalties on healthcare providers and families if they access puberty blockers, hormone therapy or surgery for a transgender child.

Concerned about the political battle over medical treatment for transgender minors, the AMA has urged governors to veto legislation that would prohibit care, saying “it is a dangerous intrusion into the practice of medicine.”

“Forgoing gender-affirming care,” the AMA wrote in a 2021 letter to the National Governors Association, “can have tragic health consequences, both mental and physical.”

Laws to criminalize care for transgender minors disturbs Marie, but it is not a topic she discusses with her son, knowing it will upset him.

“We don’t talk about what’s going on in Texas (and other states) right now because I have a lot of feelings about it and a lot of fear,” Marie said.

Though Marie has primary custody of her son, her ex-husband, she said, does not support gender-affirming care and continues to call their child by his feminine birth name. The slight, referred to as “dead-naming” among transgender people, is painful, explained Marie’ son, who has chosen the new middle name “Lion” to represent his courage.

“You just try to keep telling yourself that you know who you are,” said Lion. “I try to talk to my dad about it, but it just escalates and gets into a fight.”

When his father calls him by his birth name or refers to Lion as she or her, the fifth-grader tries to not let the pain affect him.

“I try to stick up for myself,” he said. “I try to be like Batman or the Green Lantern, tough like them.”

Last Christmas, Lion’s father wrote both his feminine birth name and his new masculine chosen name on gift tags for his presents. The gesture gave Lion hope.

“Maybe things will get better,” he said.

A child caught in the middle of a family’s polarizing views frequently experiences trauma, said Carmen Leighton, a mental health counselor who specializes in treating LBGTQ youth.

“Often we see a divide in the family, which can be very destructive,” said Leighton, a therapist at Higher Ground Services in Brewer. “And every time it falls on a trans kid who feels like, ‘I know that this is my truth, my identity, but it’s causing all of this conflict, so it’s my fault.’ ”

Parents often wrestle with fear and grief, Leighton said, when they try to understand why their child’s birth sex does not align with their chosen identity.

“It’s the fear of the unknown and it’s the grief of ‘I birthed this person and gave them this name,’ ” Leighton said. “And then this grief that I’m losing my daughter or I’m losing my son and they’re becoming someone that I may not recognize anymore.”

As transgender children become teenagers, they tend to arrive at the Portland clinic with more complex problems and needs, said Erin Belfort, a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Roughly 65 percent of the youth referred to Belfort have a mental health diagnosis such as depression, anxiety or thoughts of suicide. Some have been hospitalized after suicide attempts.

“Trying to navigate adolescence is hard enough,” Belfort said. “But trying to do so in a world that doesn’t see you as you see yourself, especially if you don’t have support at home, is incredibly stressful and traumatizing for kids.”

Belfort sees youths from every Maine county, including the state’s rural pockets, where kids may struggle to find acceptance.

Though Maine’s non-discrimination laws protect all students to ensure they learn in a safe environment, transgender youths’ experiences vary depending on which schools they attend, Belfort said.

“Kids who go to arts academies feel like they have great community and people really celebrate their identities,” Belfort said. “Then I have kids too who don’t feel safe going to school with other students who are wearing (Make America Great Again) hats and driving their pickup trucks with a shotgun in the back.”

While schools try to prevent bullying and harassment, “it still happens,” Belfort said.

The lack of mental health services throughout Maine and especially in rural areas makes it difficult for families to get their children help if they are feeling isolated or rejected.

After an initial evaluation, Belfort and doctors at the Bangor clinic refer patients to mental health providers in the community. But wait lists are long, especially in counties like Washington, Franklin and Piscataquis.

“One of our primary challenges is finding mental health clinics,” said Dr. Mayo, of the Bangor clinic. “We have patients waiting more than six months to find providers.”

Marie feels fortunate she was able to get her son treatment for his gender dysphoria. She is also grateful that Lion’s counselor is trained in the specific needs and trauma of transgender youth.

“It’s so hard to find trans competent care and people that really understand these kids,” Marie said.

Lion will likely continue taking puberty blockers until he turns 15, Marie said. Then it is unclear whether he will be able to receive hormone therapy to further transition his body.

If his father does not consent, Lion must wait until turning 18.

For now, he’s grateful that the medication is giving him the chance to be a “regular” boy who loves baseball and likes to draw.

Asked to describe himself, he quickly answers, “I’m smart, brave and competitive, yeah, and kind.”

The 11-year-old wishes people would just stop being mean to him and others who are different.

“I want acceptance for me and for everybody,” he said. “Like racism, too. I wish it would all stop.”

This series was financially supported by The Bingham Program and the Margaret E. Burnham Charitable Trust. We encourage you to share your thoughts on this series by visiting this page. Barbara A. Walsh can be reached at gro.r1751602067otino1751602067menia1751602067meht@1751602067arabr1751602067ab1751602067.