The priest quickly pulled on a black clergy shirt and a white clerical collar.

Moments earlier, Rev. Benjamin Shambaugh received an emergency call from Mercy Hospital in Portland.

“They wanted me to see a patient who was dying of COVID,” said Shambaugh, Dean of St. Luke’s Cathedral, an Episcopal church located across from the State Street hospital.

That Feb. 27 morning marked the final time Shambaugh would administer last rites to a dying hospital patient during the ongoing pandemic.

Suited in a gown, gloves, mask and face shield, Shambaugh entered the room where the elderly woman lay dying. Her son and daughter-in-law stood by the bed, faces masked.

Shambaugh greeted the patient and to his surprise, she opened her eyes and spoke lucidly.

“Would you like to pray with me?” the priest asked.

The woman nodded and smiled. She expressed gratitude for her family and asked Shambaugh to pray for them. The priest reached for her hand and began the Lord’s Prayer.

“She perked right up and said the prayer with me,” said Shambaugh.

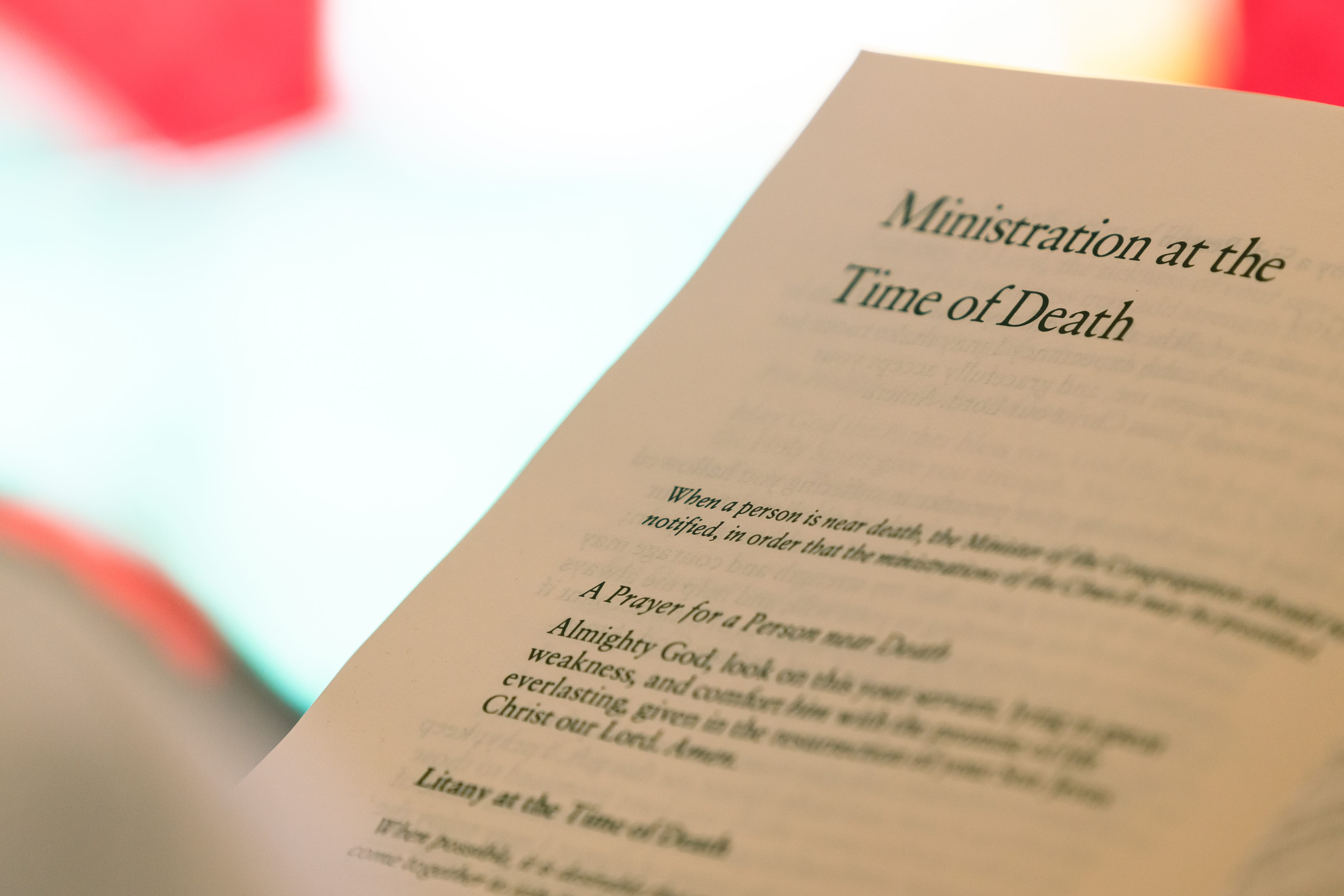

The priest also offered last rites, a sacrament Catholics and Episcopalians have received for centuries. To minimize virus spread, Shambaugh could not bring his Bible into the room or his silver ‘stock,’ a cylinder filled with holy oil. To accommodate the restrictions, he stopped at the nurses’ station and poured the consecrated oil onto a cotton ball, which he used to mark a cross on the dying woman’s forehead, absolving her sins.

Despite reciting prayers through a mask and face shield, “it was a very profound moment,” said Shambaugh.

And one that will not be permitted again for months to come.

End-of-life rituals have changed dramatically over the past two months as the coronavirus swept across the globe, infecting 1.2 million in the United States and more than 1,200 in Maine.

Some 62 people have died of COVID-19 in Maine as of May 6, but over 2,500 have died over the past two months due to other illnesses. And most of those deaths — COVID-related or not — have been affected by new restrictions aimed at diminishing virus infection.

The epidemic’s last responders — Maine’s priests, chaplains, funeral directors and hospice workers — say the highly infectious virus has upended how they do their jobs. Barred from entering most hospitals and long-term living facilities, chaplains and priests must offer comfort, consolation and prayers electronically, using Zoom or Facetime. Families are robbed of a final goodbye, the chance to hold their dying loved one’s hand as they draw their last breath.

And those who are dying of COVID — or any other illness in a confined setting — must die with strangers while longing for the touch of a loved one.

Families must also defer their grief and postpone wakes, funerals, and graveside services, unable to move forward in their journey of loss.

RELATED The Last Responders: Saying Goodbye to Dad

Along with the physical pandemic, the virus has created a pandemic of unresolved grief, said Alan D. Wolfelt, a national expert on grieving. He fears that postponing or canceling end-of-life rituals will have global repercussions.

“My concern is that we will have an epidemic of complicated grief with symptoms of depression, anxiety and addictive behaviors,” said Wolfelt, director of the Colorado-based Center for Loss and Life Transition. “If you do not acknowledge grief, you will continue to carry it.”

The suspension of wakes and funerals also has challenged funeral directors, who struggle to console families trapped in limbo, bereft of communal support.

“When someone passes away and nobody can honor their life at a wake or funeral, that is heartbreaking,” said Adam Walker, owner and funeral director of Conroy-Tully Walker funeral homes in South Portland and Portland. “There’s not much we can do at this time but offer condolences, and try to come up with creative ways to honor the decedent and comfort the families.”

During her 21 years in ministry, Rev. Carolyn Eklund has prayed at the bedside of hundreds of dying people. She takes calls at all hours of the day and night for the ritual she calls “a holy moment of connection.”

“Being there physically is so important, so the person can hear you, so you’re able to lay your hands on them and pray, weep with the family,” explained Eklund, the rector at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Brunswick. “It’s one of the holiest moments of life, if you can be there by the bedside.”

Since mid-March, Eklund, like other priests and chaplains, has been unable to console dying patients in hospitals and long-term care facilities. On March 28, Eklund received a call from a parishioner whose mother, Julia Stevens, was dying at Sunnybrook, a Brunswick assisted living facility.

“I tried to make an argument that I could gown, mask and glove up to do last rites by her bedside, but I was turned down,” said Eklund.

Concerned about other elderly patients living at the facility, Sunnybrook restricted visitors, allowing only the eldest daughter to remain at her mother’s bedside.

“I suggested to the family that we Zoom last rites so we could all pray together,” said Eklund.

As the 86-year-old Stevens, a longtime nurse herself, lay unresponsive in her bed, her five grown children, her sister and Eklund gathered on a Zoom conference call. Inside the room, the eldest daughter focused her smartphone camera on her mother.

“The siblings who could not be allowed in the room could see their mother and we all prayed together,” Eklund said.

The priest said the Lord’s Prayer and commended Stevens into God’s hands.

One by one, the children told their mother, “I love you.”

Forty-five minutes later, Stevens died.

Though the family appreciated the chance to say a virtual goodbye to their mother, it was not an ideal final farewell.

Elizabeth Stevens, who worked as a hospice nurse for many years, was heartbroken that she was locked out of her mother’s room.

“I’ve held the hands of hundreds of patients as they died,” said Stevens. “Yet I wasn’t able to hold my mother’s hand as she passed.”

Sarah Gillespie is a chaplain at St. Mary’s Hospital in Lewiston. She, like other spiritual counselors, cannot be in a COVID patient’s room. To connect with dying patients, she uses the phone, baby monitors or FaceTimes a spiritual consultation.

She witnessed one family’s farewell to a loved one dying of COVID.

“They came at the very end of life and stood outside the glass window,” Gillespie said. “I made myself available but they wanted to be by themselves. Every family has their own way.”

A Unitarian Universalist minister, Gillespie asks God to take away a dying patient’s pain, their fear, their worry.

“I ask for a loving embrace that God walks with them so that they’re not alone.”

When the virus began spreading in Maine, Gillespie adjusted her normal routine. She no longer visits several patients each day.

“To prevent cross-contamination, everyone is being a little more cautious going in and out of rooms,” she said.

Despite wearing a mask at the hospital, Gillespie was exposed to a COVID- positive patient, who was asymptomatic at the time.

“I was quarantined for 14 days,” said Gillespie. “It was hard. I have an almost 2-year-old son and I don’t want to bring the virus home.”

As she enters the hospital each day, Gillespie says the Serenity Prayer, uttering the words in her mind: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

“The prayer puts everything in perspective,” she said. “I’m not in control of anything.”

Each day at noon, Gillespie recites a prayer over the intercom to comfort the hospital’s nurses, doctors and patients during the pandemic. She asks God for courage, patience and guidance.

In the spirit of the hospital’s founder, St. Marguerite d’Youville, she always ends the prayer with ‘May we continue to love and serve.’

“I think in general, people are yearning for more spiritual practices now, whether it is prayer or not,” Gillespie said. “A lot of emotions are very high, and as chaplain I’m doing my best to support everybody.”

Hospice work is Christii Maquillan’s “heart and soul.”

Maquillan has comforted dying patients and their families for 10 years. She is the associate director of hospice development at Community Health and Counseling Services New Hope Hospice in Bangor.

“The pandemic has changed hospice unlike anything I’ve seen,” Maquillan said. “I’ve never seen so many family members standing outside of nursing homes trying to see their loved ones. It’s like their grieving started before their loved ones passed away.”

Several of her agency’s hospice nurses visit their patients and family members electronically now. Due to virus concerns, many families are declining face-to-face home visits.

“Families are scared,” Maquillan said. “As much as they want hospice nurses to come help them and their loved one, they are afraid of the virus and what we may bring in to them.”

Several hospice workers have stood outside patients’ homes, placing notes in the windows to help families with end-of-life care.

“We still want to lay eyes on people,” explained Maquillan, “to know they aren’t suffering.”

Last December, months before Maine patients were diagnosed with the virus, Maqullian’s husband, Robert, died of cancer. He was 59 and they had been married for 30 years. Maquillan, her children and a hospice nurse cared for him at home.

“I was laying right beside him when he died,” Maquillan said. “And his kids were there, too. It was the greatest gift we could have given him.”

The thought of husbands, fathers, and parents dying in hospitals or nursing homes without family by their side sickens Maquillan.

“No amount of medicine is going to take away a patient’s anxiety, fear or replace the physical presence of the people that person loves,” said Maquillan.

Caring for dying patients with dementia, Maquillan says, is particularly hard without family.

“Seeing all these people with masks and gowns around them is scary, and they don’t understand why their loved ones aren’t there.”

Once a patient dies, families are left with few options for communal end-of-life rituals. Due to pandemic restrictions, funeral homes must limit gatherings to five people for viewings or wakes and 10 people for a private service or burial.

“It’s invite only,” explained Justin Richardson, a funeral director and general manager of Family First Funeral Homes & Cremation Care, which operates five homes in central Maine. “We’re not allowed to do any public services. If the family wants to see their loved one again in a casket, we let them know what the rules are as to how many they are allowed to have, and we set up different times for viewings.”

After each group of five people offers prayers and farewells, the funeral home is sanitized before the next group enters, Richardson said.

Each family handles the restrictions differently. Some are angry. Others are sad, mournful that their loved one’s life cannot be publicly honored.

“You can shut down restaurants and movie theaters, but you can’t quarantine grieving,” Richardson said. “The virus adds another layer of grief to a family’s loss.”

Families were especially upset when the state’s virus restrictions went into effect in mid-March, banning gatherings of more than 10 people. Some had already planned wakes and services that had to be canceled.

“So, on a Monday we planned services, and then we found out on a Wednesday or Thursday that they had to cancel wakes and funerals,” Richardson said. “Those were tough calls to make to the families.”

James Fernald’s family opened an undertaker business in the mid-1800s on Sutton Island near Bar Harbor. His family has been caring for the dead for six generations. Now funeral director of Brookings-Smith, which owns funeral homes in Bangor, Blue Hill and Bar Harbor, Fernald is proud to be called a ‘last responder.’

As the pandemic ravages the globe, killing more than 260 thousand, funeral directors like Fernald recast themselves as ‘last responders,’ a crucial tier in the healthcare crisis.

The new virus restrictions, Fernald said, impact nearly every aspect of their jobs. Funeral workers take extra precautions now when they pick up the deceased’s body. Masks are placed over the body’s nose and mouth once they are removed from their transport bag.

“When we move a body, it can expel a bit,” explained Fernald, a former Maine Funeral Directors Association president. “So we are making sure no COVID virus enters the air.”

The longtime tradition of meeting families face-to-face to make arrangements has also changed, hampering the grief process, Fernald said.

“The first reality of the death actually happens when you get in your car and drive to the funeral home and make arrangements for your loved one,” said Fernald. “That’s an emotional time, another step in accepting the reality of the loss.”

Many families now prefer to make arrangements over the phone, Fernald said, which is difficult for both funeral workers and people living in small Maine communities.

“When many of the families come through the door, they are people we’ve known for years, and we’ve handled several generations of their family,” said Fernald. “It’s common to give them a good hug or shake hands. We can’t do any of that now.”

Instead, the last responders are left with few answers and little consolation.

“We apologize to families and tell them we will eventually hold services and burials,” Fernald said. “We tell them we just need them to be strong for a little bit and to know we are going to get through this together.”

Funeral Director Adam Walker shares Fernald’s belief that Mainers must remain strong until the virus diminishes, but the long shifts, the 10-day stints, the constant sanitizing of the funeral home, the hearse and themselves can be difficult and exhausting.

“We have our good days and our bad,” said Walker, who alternates shifts with his fellow funeral director, in case one of them contracts the virus.

The two Conroy-Tully Walker funeral homes are located within minutes of Maine Medical Center and Mercy Hospital in Cumberland County, which has most of the state’s COVID infections, with 583 confirmed cases and 30 deaths as of Wednesday.

Walker, who began working at a funeral home when he was 16, has sought ways to comfort families that are denied large gatherings at a wake. Using a tip from another funeral director, Walker created ‘Hugs from Home’ as a substitute for the crowd of friends, coworkers and relatives who would normally attend a wake.

Walker invites people to send the funeral home messages of support and love to bolster the families’ spirits. The notes are placed on cards attached to balloons, which are tied to the viewing room chairs.

“The families are blown away when they walk in and see all the balloons,” Walker said. “It gives them a sense that they are not alone; they don’t have to mourn in an empty room.”

Over the past two months, Walker and many funeral workers have had little time off.

Their dedication did not escape Pope Francis, who called attention to funeral home workers during a March 20 Vatican Mass, asking for prayers for beleaguered last responders.

“What they do is so heavy and sad,” he said. “They really feel the pain of this pandemic so close.”

As the coronavirus continues to spread with predictions of a fall resurgence, the last responders will continue to do their best to comfort the dying, the dead and the grieving families.

Months after Rev. Shambaugh administered last rites to the dying patient at Mercy Hospital, he still reflects about the woman he anointed.

“She smiled at me as she talked about how grateful she was for her family,” the priest remembered. “And I told her, ‘You can’t see it behind my mask, but I’m smiling, too.’ ”

“I can see your smile in your eyes,” the dying woman replied.

Shambaugh cried before leaving the hospital, grateful for the privilege of bearing witness to one of life’s most holy moments.

“Death,” explained Shambaugh, “is one of those thin moments, the border between this world and the next. Our jobs are to be with people as they make that transition and to be there with the family to give them comfort and peace.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misstated that St. Mary’s Hospital Chaplain Sarah Gillespie could not enter rooms in the intensive care unit. This story has been updated to reflect that is no longer true.