In his State of the State address last week, Gov. Paul LePage continued his attack on the tax-exempt status of Maine’s 75 private land trusts, claiming they take hundreds of millions of dollars of land value off the tax rolls.

“School budgets are not commonly blamed, but are normally blamed for tax increases,” LePage told legislators “The real culprit is the tremendous amount of land and property value we’ve allowed to be taken off our tax rolls, leaving homeowners to pick up the tab.”

Over the past month, Pine Tree Watch has been investigating issues related to what the governor brought before legislators. We found that for many municipalities in northern Maine, conservation is viewed as drastically cutting into potential — and desperately needed — tax revenue and that views about conservation differ greatly in Maine depending on where it’s happening.

“These landowners must contribute to our tax base,” LePage said in his address. “It’s time for all land and real estate owners to take the burden off homeowners and pay taxes or a fee in lieu of taxes.”

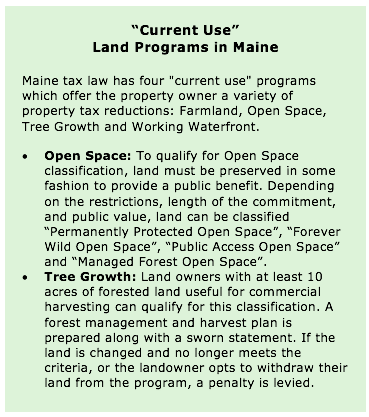

According to land trust advocates, though, most land managed by land trusts in Maine is still on local tax rolls. However, because of the public benefit these lands are intended to provide in the way of conservation, many landowners get significant property tax benefits. In some cases, land is taxed at only 5 percent of its fair market value.

Maine is among the leaders in the country in conservation through private stewardship, with land trusts holding conservation easements on 1.9 million acres of private land, and owning 600,000 acres of public-access preserves. That amounts to more than 10 percent of the state’s land.

While most of this acreage is preserved land in Maine’s unorganized territory, having no impact on local budgets, some small communities in Maine say the property-tax breaks land trusts receive drain their tax bases and threaten their sustainability.

“It, in fact, is accelerating the shrinking of the small towns’ economies, particularly the coastal towns,” said Jimmy Clark, a Machiasport tax assessor working for two municipalities in Washington County.

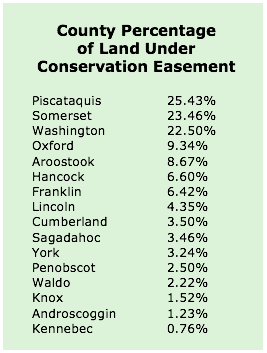

Washington County has 22.5 percent of its acreage under conservation easement, trailing only Piscataquis County at 25.4 percent and Somerset County at 23.5 percent, according to Pine Tree Watch’s analysis of the Conservation Lands Registry, which is a self-reported and incomplete database of all easements in the state.

Such percentages of eased lands are unseen in the central and southern parts of Maine. Kennebec County — including the Augusta and Waterville areas — has only 0.76 percent of its land under easement.

To see how communities in northern and southern Maine are impacted differently by the property-tax losses that come with private conservation, Pine Tree Watch looked at the financial reports of two towns in very different circumstances:

• In Cumberland County, the town of Cumberland (7,211 residents) with a total assessed land value of $1.3 billion, lost $218,065 last year in property-tax revenue to land trust holdings and tax-exempt town- and state-owned parcels (a total of 1,933 acres).

• The town of Lubec (1,359 residents) in northeastern Washington County, with a total assessed value of $130 million, lost $175,035 in revenue in 2016 to land trust holdings alone (2,663 acres).

Factoring in the massive difference in the two towns’ land values, Lubec lost more than 10 times of its property tax base to private conservation compared to Cumberland.

“When people ask me why taxes are going up, I tell them 25 percent of your landmass now is in some sort of full or factored tax-exemption,” Clark said.

Land trust advocates maintain that 94.5 percent of preserved land is on the tax rolls, and on 4 percent of the acres, the land trust makes payments in lieu of taxes.

“At a minimum, we pay for what the land would be on the tax rolls under Current Use, and sometimes we pay a little bit more,” said Jeff Romano of the Maine Land Trust Network. “Land trusts recognize that they want to be part of the community and that’s part of the relationship.”

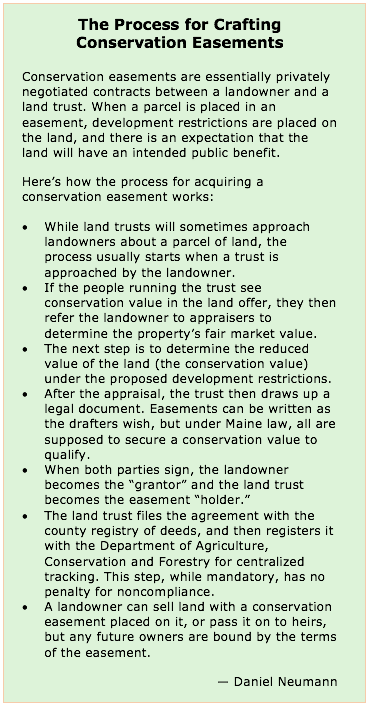

Each conservation easement is unique and their tax benefits vary. Some restrict housing development, others limit or ban mining, forestry, access or certain types of recreational activity, like snowmobiling or trapping. Generally, the tax reduction tends to be greatest for highly restrictive easements on prime development land in an area experiencing rapid growth.

A property owner creates a conservation easement by donating the development rights of their land to a land trust. The property owner then claims the difference in the adjusted value of the property as a charitable gift deduction on their income taxes.

Depending on the development rights donated, a forested parcel designated as Public Access Open Space could be assessed at only 5 percent of its fair market value. In Piscataquis, Somerset and Washington counties, roughly a quarter of all taxable land could be assessed at significantly reduced rates.

The total impact on private conservation on local property tax bases in Maine is not publicly known. The Joint Standing Committee on Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry is due to report later this month to the state Legislature on, among other things, property tax payments that land trusts make on their conserved lands.

“Our members are deeply concerned about the financial realities of running a municipal government, now probably more so,” said Eric Conrad, director of Communication and Educational Services for the Maine Municipal Association.

Conrad said MMA members are divided on the issue of conservation easements. While many favor preserving the character of the state through conservation, poorer communities more dependent on property taxes feel conservation comes at their expense.

“How do we improve quality of life with open space in this age of state and federal government supporting us less, yet asking more of us?” Conrad asked. “That’s the overarching thing that our (members) have to deal with every day.”

Cumberland is striking a balance between development and open space

The MMA says member municipalities with diversified tax bases and available land often work well with land trusts. In some cases, land trusts use their state-mandated comprehensive plans as guides for acquiring new conservation easements and preserves.

“As long as that is done in concert with the town, and its comprehensive plan, and its financial pressures, (municipalities and land trusts) can work together pretty well,” Conrad said.

In southern Maine, Cumberland County has only 3.5 percent of its land set aside under 320 conservation easements. The Chebeague & Cumberland Land Trust owns two of the county’s largest publicly accessible preserves, including the picturesque 300-acre Knight’s Pond Preserve that boasts ponds, wetlands, streams and many vernal pools. The trust’s website promotes trails that pass through oak and hickory forests.

Bill Shane, Cumberland’s town manager, says that land trust holdings are 0.43 percent of the total acreage of the town.

“It’s a non-issue,” Shane said. “I guess that’s the best way I can describe it in Cumberland.”

Last year in Cumberland, 62 acres were held by land trusts, and another 244 acres were classified as Open Space. Cumberland has 14,400 acres total and an assessed town value of $1.3 billion.

“It’s a pretty small percentage of the big picture, so it doesn’t have the kind of impact you see Down East or in northern Maine,” Shane said.

By comparison, Lubec, with its much smaller population, property value and tax base, has 2,663 acres held by land trusts taxed at a reduced Open Space assessment. Lubec has 24,500 acres total and an assessed town value of $130 million.

In all, Cumberland’s tax-exempt and tax-reduced land, including schools, churches, utilities, town and state properties, as well as land trust holdings, totals 13 percent of the town’s total landmass.

Shane explained that there is a sweet spot a municipality tries to find in its land management to not curb growth, and that Cumberland does not want much more than 13 percent of its land to go off the tax rolls.

“You know, our experience is it’s all a balancing act. Somewhere in that 10 to 15 percent range might be as far as you want to go,” Shane said. “How much is too much? Because you do need land to develop and sustain a community.”

Lubec assessor: Town feels like silent partner in its own development

Washington County lies far outside the Cumberland town manager’s proposed sweet spot. Conservation easements cover 369,018 acres — 22.5 percent — of the county’s 1.6 million acres. This does not include state- and town-owned property and other tax-exempt land in the county, which would push its percentage of tax-reduced lands even higher.

Among MMA members, Conrad said Washington County municipalities — towns with large amounts of land they desperately seek to develop because they need the economic help — have an entirely different point of view.

“When they see a prime parcel go up for conservation, they are like, ‘ugh’,” Conrad said.

Washington County has a population of 31,625, with 18.5 percent of its residents under the federal poverty line. The only two counties with more glaring poverty numbers are Piscataquis and Aroostook.

Recently, the New York-based Butler Conservation Fund acquired about seven miles of shoreline worth an estimated $2 million in Lubec. Town officials say they were not consulted ahead of the deal.

While the Butler Fund’s organizers point to the potential economic benefits increased tourism dollars will bring to Washington County, those kind of economic-benefit promises tend to fall upon deaf ears in towns similar to Lubec.

“I’m for conservation,” Lubec assessor Clark said. “But the community feels like silent partners here.”

“They keep saying, if they build it, they will come,” he said, referring to the tourism boon land trusts tout in many of their promotional materials. But Lubec is struggling to find the funds to raze dilapidated buildings. Clark fears blight will dissuade any tourists who do make the trip from coming back.

The Butler Conservation Fund joins the Maine Coast Heritage Trust and the national Nature Conservancy, two of the state’s biggest private holders, along with 14 other land trusts in managing 141 conservation easements and preserves in Washington County.

The 2016 Lubec annual town report listed a total of 39 parcels either directly owned by a land trust or owned by a private owner with a land trust holding the easement. Assessed at fair market value, those 39 parcels have a value of $8,672,410.

After being assessed as Open Space, the value of the parcels drops to $1,095,116.

According to the Clark, the variance between the fair market value and the Open Space assessment equals a loss of around $175,035 in annual tax revenue for the town. That amounts to 10 times the property tax loss that Cumberland sees, when you factor in the land valuation of each town.

And it is 5.8 percent of the town’s $3,028,730 net assessment for commitment — the minimum property tax revenue the town needs to fund its annual service commitments.

Among those parcels conserved by land trusts in Lubec, 25 are classified “Open Space Public Access” and are assessed at just five percent of their fair market value.

“You know, this one-size-fits-all program is not fair,” Clark said.

Constrained sellers unload prime parcels

In 2013, the Maine Coast Heritage Trust raised $1.1 million to purchase a 66-acre preserve called Long Point and has since added some adjoining properties. Once considered for a housing development, this prime parcel covers more than two miles of undeveloped shoreline in Washington County’s Machias Bay.

Before the purchase, Long Point was a privately owned woodlot classified for valuation purposes as Tree Growth forest land, and thus assessed at a reduced value. The state sees value in giving landowners tax benefits to promote tree growth.

When a classified-use property is changed or sold, the last owner is levied a penalty to recoup the state’s investment. This can be a significant financial restraint for many owners trying to sell their restricted land.

Clark believes the large amount of coastal lands classified as Tree Growth in Washington County disincentivizes owners to sell to any buyer other than land trusts because they can avoid future penalties due to their tax-exempt status.

“(Land trusts) have a list of all these parcels around the state and they target them because they’re beautiful,” Clark said. “They show up when they find out that a person’s going to sell and start negotiating with them to unload it.”

According to Clark, because of the Tree Growth classification, Long Point’s sellers could have been fined nearly $250,000 had they sold to a buyer that didn’t have tax-exempt status.

The inability to recoup penalties in such transactions is also a loss to small municipalities. Clarks estimates that in the last 10 years, he has seen $1 million in potential revenue lost this way.

Municipalities ask for a seat at the table

Land trusts in Maine have built 2,450 miles of trails for hiking, mountain biking, snowmobiling and ATV riding, according to the Maine Land Trust Network. Trusts have created 616 public access sites to fresh and coastal waters, including boat launches, beaches and swimming areas.

Maine has comparatively little federally owned and protected lands compared to other states. The trend toward private conservation has risen here as a result. However, in the past few years, several bills designed to end tax-exemption eligibility for land trusts failed to pass the state Legislature.

The economic and political costs and benefits of private stewardship of lands has gone largely unstudied in the state. Conservation easements are seldom weighed against other conservation methods, such as restrictive zoning and direct public management.

“The lack of data on the amount of public subsidies committed to conservation easements is a problem for policymakers who must determine whether that sum, large as it must be, could be better spent on a combination of easements and public land acquisitions,” wrote Jeff Pidot, a former head of the Natural Resources Division in the Attorney General’s Office, in 2005.

Pidot said recently he believes including public oversight in some capacity at the outset could benefit how conservation easements are crafted.

“There are conservation easements in Maine, even today, with what might be considered to be a somewhat marginal value to the public,” he said.

Massachusetts has added public oversight to its private conservation system, requiring public hearings before a conservation easement is approved. There is no such mandate in Maine, nor an initiative to add it to existing state law.

Warren Whitley of the Maine Land Trust Network believes mandating public hearings when easements are created is a remedy in search of a problem.

“I think most people will say the last thing we need is more oversight, or anything like that,” Whitley said.

Some counties and municipalities are working closely with local land trusts to plan the future of their towns. In other communities, rifts are emerging.

Conrad, at the Maine Municipal Association, feels local officials need to be heard by conservationists.

“The elected officials, town managers and town planners have some degree of responsibility over their future,” he said. “I don’t think they expect to control it, but they at least deserve to be at the table.”