WATERVILLE — This fall, on an unseasonably warm day in a warehouse on a dead end road, Chris Martin, founder of Give IT. Get IT., reached into a box of iPhones and turned one on. The phone appeared unblemished — no cracked screen or scratches, no missing buttons. A forklift beeped in the background.

“It’s a perfectly good phone,” he said, as the device blinked on.

Cell phones are a small portion of what Martin takes in at his refurbishment and recycling business. But the boxes of working phones in his warehouse are emblematic of a larger issue: Mainers are generating more electronic waste than ever. And no one knows what percentage of that waste is sent for recycling.

That’s a problem. Without understanding what’s available to be recycled, Maine does not know how successful its program is at diverting products from landfills, where discarded electronic devices can leach toxins.

The state has no idea whether a drop in e-waste collection over the past six years is due primarily to lighter devices, fewer devices being collected for recycling — or both.

It also makes it difficult to identify areas for improvement in the state’s acclaimed program. Should the list of what’s covered be expanded? Are collection events the best way to gather electronics in rural areas?

Without knowing what’s out there waiting to be recycled, those questions become impossible to answer.

“We don’t know what the denominator is. We don’t know what percentage we’re actually collecting back,” said Sarah Nichols, a waste policy expert with the Natural Resources Council of Maine, which was involved in crafting the initial e-waste law, passed in 2004. “How do we measure if it’s successful or not over time?”

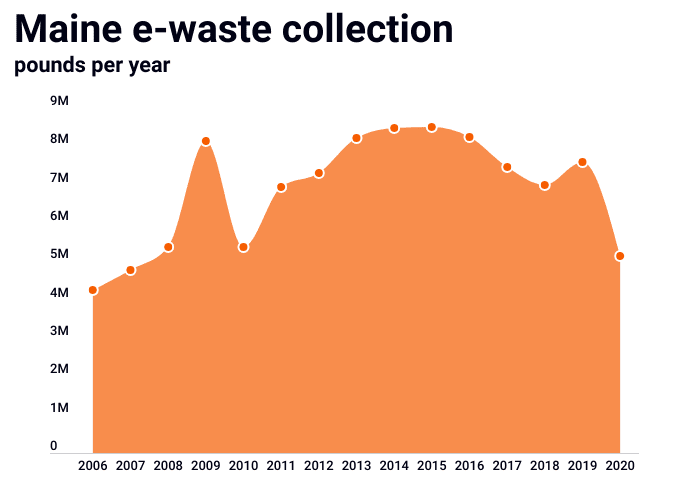

Consolidators, the companies that collect and sort e-waste to send to recyclers for processing, brought in 5.1 million pounds of discarded electronics last year, according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. That’s a 40 percent drop from 2015, when collection peaked at 8.5 million pounds. Rates have been falling for years, even before the pandemic disrupted collections, with transfer stations limiting operations and collection events postponed.

Devices such as televisions, laptops, printers, monitors and notebooks have gotten lighter and smaller. That accounts for at least part — and perhaps most — of the drop in collection, which is calculated by weight. But because neither the state nor the federal government tracks product generation, no one knows what percentage of Maine’s e-waste we’re actually saving from being sent to the landfill.

Why is Maine’s number so low?

United Nations University, an organization that monitors the problem worldwide, estimates that in 2019, Americans generated 46 pounds of e-waste per person. That same year, Maine collected 5.64 pounds per person — 12 percent of what U.N.U. estimates was probably generated. That number fell to 3.82 pounds in 2020.

The university, however, uses a more expansive definition of electronic, encompassing anything with a cord or plug, while Maine law primarily covers televisions, printers and monitors (cell phones aren’t legally included, but retailers are required to accept them for recycling at no charge).

Another problem is that the most recent figures available from the state are more than a decade old, when a DEP report on Maine’s program estimated that consolidators captured half of the household computer monitors and televisions available for recycling in 2008, up around 6% from when the program began in 2006.

DEP staff say the primary reason for the drop is likely that, until recently, a significant portion of the state’s e-waste stream was made up of boxy, lead-filled cathode-ray tube (CRT) televisions, which are much heavier than the flat screens of today.

In 2010, the average piece of computer equipment received by Maine’s program weighed 31.8 pounds. Five years later, that had fallen to 21.9 pounds, a 31% drop, according to the state’s annual Product Stewardship Report. Other states with e-waste programs are seeing similar declines in collection rates. Without tracking generation, however, it’s impossible to know for sure how effective Maine’s (or any) e-waste collection program really is.

Why effectiveness is hard to measure

Waste generation is difficult to pin down, as there’s no universal definition of what’s considered electronic. There’s no federal law governing e-waste and state definitions vary wildly.

In Maine, e-waste covered under the law is limited to televisions, portable DVD players, game consoles, computer monitors, laptops, tablets, e-readers, 3D printers, printers, digital picture frames, and other visual display devices with screens of at least four inches measured diagonally and one or more circuit boards.

Another difficulty with trying to figure out how much e-waste Maine generates is there is no clear time frame for how long each product is in circulation before it enters the waste stream. Some could be around for years, others for just a few months.

Lacking consistent data to compare programs between states, experts typically evaluate programs based on how much weight they’re collecting per capita, and whether they’re collection programs are convenient for residents. On those fronts, Maine measures well, said Scott Cassel, founder of the Product Stewardship Institute, an organization that helps design producer responsibility laws and programs.

Maine has long been a leader on extended producer responsibility, or EPR, the idea that manufacturers should pay at least some of the cost for disposal of their products. Even with the drop in recent years, the state consistently ranks among the highest pounds per capita in e-waste collection rates, and experts say the program’s convenience and the wide scope of products it collects make it one of the better programs nationwide.

Only half of U.S. states have adopted any kind of legislation aimed at managing e-waste. Many states still allow electronics to be tossed into landfills, even though devices can leach toxins like mercury and lead. As of 2020, only about half of the 50 states had any kind of landfill ban in place.

“All this stuff around the world should be banned from landfills,” said John Shegerian, CEO of ERI, a national electronics recycler and one of Maine’s DEP-approved consolidators. “All this stuff should be going to responsible recyclers.”

Cell phones and devices containing mercury or cathode ray tubes (many older TVs and monitors) are banned from landfills in Maine, but many other electronics are not, said Elena Bertocci, who manages the e-waste program for the DEP. “The rest can technically go (to a landfill). It doesn’t mean it should, but it can.”

Mainers toss millions of pounds of good devices

It’s also clear that many of the electronics that wind up in the recycling stream ideally shouldn’t be there at all: Every year, Maine residents throw out millions of pounds of products that work just fine. They may not end up in landfills, but processing them — for recycling or refurbishment — takes time and resources.

Of the flat screens TVs measuring 42 inches or less in the warehouse of North Coast Services, a consolidator based in Portsmouth, N.H. that handles the majority of Maine’s e-waste, Billy Andrews, one of the company’s founders, estimates that 80% are in working condition. But since he’s not in the refurbishment and resale business, those get sent to processors to be broken down along with everything else.

“People don’t want them anymore because they’re not big. It’s not a smart TV. It doesn’t have a camera. It’s something new every year. Just wait for Walmart and Best Buy to put out their ads here in a week or so, and everyone will be going for that. And the minute they get it…” he trailed off. “They just don’t want to hang onto the old.”

Martin, of Give It. Get It. in Waterville, which is in the refurbishment and resale business, agreed. He pointed to a box of iPhones.

“There’s a whole pile of them in here, but they’re perfectly fine. What happens is this behavior is not driven by the consumer. This behavior is driven by the manufacturer. They’re built for the dump, designed for the dump,” Martin said.

Replacing phone batteries, for instance, was once a simple matter of opening the back and popping in a new one, which could extend the life of the phone by years. Now batteries are often glued in place. Taking batteries out of tablets and laptops, said Martin, is a nightmare. “You end up breaking the whole thing.”

Creating financial incentives for manufacturers to design products that are less toxic and easier to recycle was one of the goals of Maine’s e-waste program. It hasn’t worked out the way advocates had hoped.

“Those are just incentives, not mandates,” said Nichols, of the Natural Resources Council. With a patchwork of laws around the country, it’s unlikely a small state like Maine would be able to influence design changes through fees alone. Companies would likely pay them and continue designing products as they see fit, she added.

Some countries are attempting to force companies to design products with repairability and end-of-life in mind. France recently passed a law requiring manufacturers to rate repairability of their products, and the United States has something similar in the EPEAT registry, which rates products based on sustainability, but doesn’t put as much emphasis on repairability.

“This equipment is mined, manufactured, transported, used and then thrown out. That is crazy,” said Cassel. “It’s absolutely insane.”

Consumers already have the legal right to repair most of the products they buy, but practically speaking, companies often keep them from being able to do so by withholding parts or information.

Right-to-repair legislation, which aims to close those gaps, has been introduced in several state legislatures in recent years but has been fought by companies that say it could pose security risks and threaten intellectual property. The movement did get a boost this year when the Federal Trade Commission voted to enforce laws around the right-to-repair, and recently when Apple announced that it would make parts, tools and manuals, starting with the iPhone 12 and 13, available to individual customers.

“Repair is a really big deal in electronics because they turn over so fast and they’re so resource-intensive to make,” said Bertocci.

“Recycling is great,” said Nichols, “but we really need to do better at reducing. When you’re transporting all these materials all over the place it kind of counteracts the climate benefit of [recycling].”

Yet, recycling is still important. There are enormous potential resources in discarded electronics, and advocates have long dreamed of a robust system for “urban mining” of e-waste, which contains valuable, mined minerals such as gold, copper and lithium.

“Why do we need to go dig for new materials when we can recycle our old ones?” asked Shegerian. “It makes no sense.”

Less weight means less revenue

Even if Maine does not know for sure why it’s occurring, the drop in statewide electronic collection weight could present a problem for companies that handle Maine’s e-waste, as they’re paid in part based on how many pounds they bring in each year.

Companies that sell electronics covered under the state’s e-waste 2004 product stewardship law pay two separate fees: an administrative fee to the state, and a weight-based fee to consolidators, the companies that pick up and sort the e-waste before sending it on to processors outside the state.

In 2020, about 60 manufacturers paid $2.4 million to recycling handlers to cover the cost of managing discarded devices, down from $3.5 million in 2019 and $3.4 million the year before. The pandemic played a large part in the 2020 drop: The DEP estimates that collections were down roughly 33% due to events being cancelled and transfer stations altering operations.

Andrews, a founder of North Coast, was worried that the disappearance of CRT televisions from the waste stream would create a significant drop in revenues for consolidators. CRT televisions still make up around 60 percent of what North Coast collects, but that’s declining monthly. “It was a huge concern of ours,” said Andrews.

Every fall, consolidators propose a price per pound for handling, transportation and recycling of each type of device in four geographic regions. Prices are capped by the DEP at 48 cents per pound.

In recent years, consolidators have expressed fears that the per pound price won’t be enough to cover costs of picking up and processing waste from more rural areas, according to a memo written by DEP staff this fall.

The state lost one consolidator in 2018, said Andrews, in part of what he characterized as cost issues related to picking up e-waste from remote areas. “Geographically it’s a tough place to service.” The number of consolidators approved to pick up e-waste has dropped dramatically since weights peaked six years ago, from 10 in 2015 to four in 2021.

Local collection days worry consolidators

Collection events, in which municipalities in rural areas come together once or twice a year to gather discarded electronics, may be an efficient way for communities to collect their e-waste, but they’re not ideal for the companies picking up the waste, said the DEP’s Brian Beneski, testifying in front of the legislature earlier this year on proposed amendments to the state’s e-waste law.

Consolidators are often “hesitant to service collection events,” said Beneski, because they can’t be certain how much waste they will get. That makes it difficult to know whether they’ll cover their costs.

The DEP is in the midst of drafting rules aimed at regionalizing collection to make it easier for consolidators to service rural areas, as well as to ensure non-covered devices aren’t included in shipments and to increase incentives for green product design.

So far, at least, it seems Mainers are making up for a decrease in weight with an increase in volume.

“We’re getting so many more flat screens, quantity-wise,” said Andrews. “Before we’d go to a transfer station and if it was all [CRT] TVs, you’d pick up 100 TVs. Now we’re going to a transfer station and we’re picking up 60 [CRT] TVs, but we’re picking up 100 flat screens.”

Fees unchanged in more than a decade

It’s also the case that administrative fees, which are paid to the state, have been set at the same level since 2009 — $3,000 for manufacturers with 0.1% or more of market share, and $750 for everyone else.

“Apple, Dell… You’ve got people selling huge, huge amounts of electronics into the state and they only pay $3,000,” said Bertocci. The fees, which brought in slightly more than $200,000 in 2020, do cover the costs of administering the program, she said, but “some people might question the fairness of it.”

Administrative fees often make up a small portion of what manufacturers pay overall, however.

In 2020, apart from its $3,000 administrative fee, Samsung paid $619,665 to dispose of televisions, while Dell Marketing paid $39,608 to consolidators to cover the recycling costs of monitors through the program. Apple paid $15,208 into the monitor category.

The way Maine’s system works, manufacturers pay in advance for the recycling of their products.

But manufacturers say Maine’s program is costly compared to other states, and there isn’t enough competition among consolidators to keep prices down and investment in the business up.

“Our members that participate in the e-waste program in Maine and in other states around the country have told us that there are more efficient and effective models and programs in other states,” wrote Curtis Picard in testimony last year on a bill, opposed by the DEP, that would have dramatically altered the program. “They have told us that Maine’s program is one of the costliest in the nation.”

Maine might be able to lower costs by adding personal computers to its list of covered devices, said Jason Linnell, executive director of the National Center for Electronics Recycling. A 2019 audit of the program made a similar suggestion. “Recycling of TVs clearly would not be cost effective absent EPR, while recycling/resale of PCs may be viable in an open market,” the authors wrote.

Personal computers towers, like cell phones, weren’t included in the original law because they have value on the scrap market, unlike CRT televisions, which cost more money to process than they’re worth. Electronics that have more value in scrap could offset the low value products.

Covered devices list unchanged since 2009

Without knowing what’s available in our waste stream for recycling, it’s also hard to know whether we should expand the list of products covered under Maine’s product stewardship laws. Of the states and jurisdictions that do have e-waste laws on the books, the list of products covered under those laws varies dramatically. The most comprehensive is the European Union, which, like the U.N., considers e-waste to be anything with a cord or plug.

The EU also boasts much higher e-waste collection rates than the U.S., at around 35% each year. Cassel argues for an expanded definition here in Maine, and in the U.S.

“Anything with a cord and a plug should be included,” said Cassel, who’s been working on e-waste legislation for decades. “I think that we’ll eventually get to that place here in the U.S. Everything has been a fight with manufacturers on this.”

Nichols of the NRCM said the group would potentially like to see the scope widened.

“We would like to see it expand to include more products in general, especially since the nature of electronics has changed so much since the program was established,” said Nichols.

The state doesn’t have a position on whether the list of devices covered under the law should be expanded, said Bertocci. Any changes to the list or to administrative fees would have to be made by the legislature.

There are options for electronics that aren’t covered under the program. Consolidators will process them, said Andrews. Staples and Best Buy both run electronics take-back programs. But a number of appliances — air conditioners, mini fridges, heaters — are left off the list, and residents may have to pay for disposal, which officials agree may discourage recycling.

Best Buy charges $99.99 for pickup of larger items, such as refrigerators, stoves, dishwashers and microwaves, unless a consumer also buys a replacement from the company, in which case the disposal fee is $29.99. The programs are also run voluntarily, which means the list and fees could change at any time.

Transfer station operators are doing a much better job in recent years informing residents that electronics, even those that aren’t covered under the program, shouldn’t go in the trash, said Andrews. Without data on what’s available for recycling, however, it’s difficult to truly know what is being diverted.

Andrews said the amount of electronics North Coast collects that aren’t covered under the law is small. The company processes them even though it cannot bill manufacturers for their disposal.

“The other stuff is really such a low volume, comparatively speaking,” said Andrews. “Keyboards, mice, VCRs, toasters — we still collect that. We bill the transfer stations and they bill people.” A transfer station might charge $2 to dispose of a VCR, for instance, said Andrews.

Expanding the list of covered items manufacturers are responsible for could get complicated. It would be tough to bill a manufacturer for disposal of many small electronics, said Andrews, because it can be difficult, if not impossible, to determine where they come from.

“They’re from these very obscure manufacturers that aren’t even going to be around in a year,” said Andrews. “Responsibility is really hard to trace.”