“We are not the helpless subjects of evolution. We are evolution.” — Erich Jantsch

A baby goes from crawling to walking in a matter of months with almost no coaching. It’s a system of trial and error, tipping and falling, progress and regression, experimentation, and self-correction. Babies teach themselves to walk by watching the world around them and advancing through self-motivation, loosely structured group interaction and practice. This is the optimal learning system for humans but unfortunately, human organizations rarely use it.

Think how a baby learns to walk. Now picture how we teach students. Then visualize how organizations typically supervise adults at work. Finally, contemplate how governments rule from remote capitals.

Then think again about how a baby learns to walk. Can you see a disconnect between how humans are naturally wired to learn and grow?

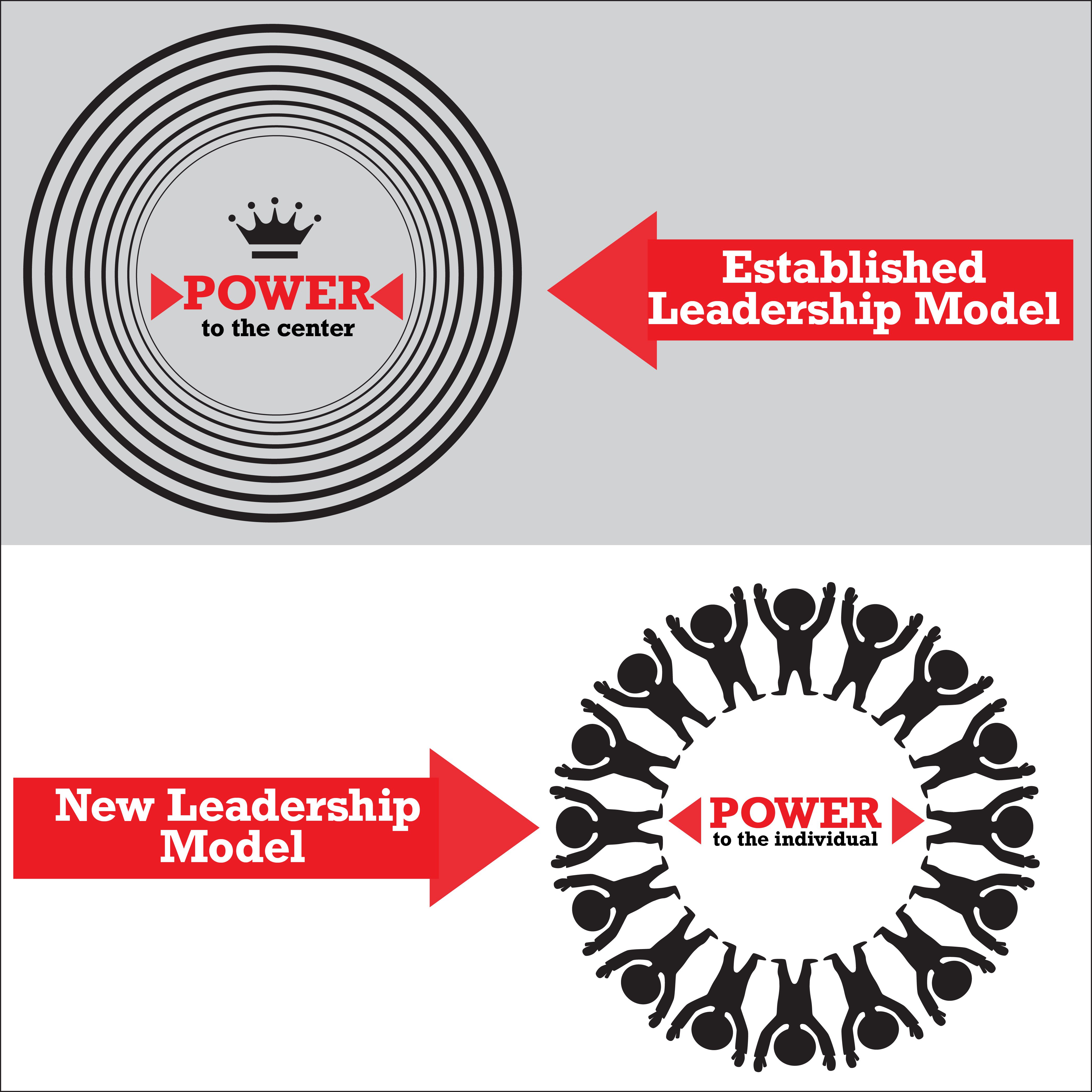

Our systems for teaching, managing and governing are all top-down and standardized exercises in following and conformity. A baby aspiring to walk has more freedom to acquire that complex skill on its own than a 16-year-old has in English class, a mature adult has at work or a responsible citizen has during a pandemic. Control and standardization from the center: That’s how we’ve come to teach, train, direct and un-inspire.

Now, think one more time about how a baby learns to walk. Next, consider how we might reimagine our learning and governance systems.

Discovery in rural India

Over a decade ago in remote villages across India, Sugata Mitra conducted a series of exceptional social experiments designed to better understand how children learn. In dirt-covered town squares where kids congregated, he inserted a computer screen and control panel with Internet access into a randomly selected wall. No instructions were left behind. No adults stood by to invite children to gather and then teach them what to do.

Here’s what happened next . . .

Within hours, a child would find the device and begin experimenting. This child, like all others who participated, had never used a computer or been on the Internet. To add to the complexity, the computer language was English, which none of the children in the region had studied or spoken.

In less than 10 minutes, that first user was successfully browsing the web. By the end of the first day, dozens of children had congregated, taken a turn and learned to use the device. Within weeks, the group knew hundreds of English words and achieved advanced Internet navigation skills to play games, watch shows and gather information. When later tested on proficiency, the children typically passed. Everyone earned the same high grades. Rarely were there discrepancies in learning.

“Big parts of primary education can actually happen on their own,” Sugata said. “Learning does not have to be imposed from a top-down system. In nature, all systems are self-organized. Learning is ideally a self-organizing system.”

Sugata then described from his research the four optimal conditions for learning:

- Fault tolerant

- Minimally invasive

- Fluid, allowing free-flowing connectivity with others

- Self-organizing

Humans know how to learn

In 2021, Hancock Lumber was recognized as one of the “Best Places to Work in Maine” for the eighth straight year. Across 16 sites and 600 employees, our engagement score was a 90 compared to the national average of 34, according to Gallup polls.

What training systems were involved to earn such a score? None.

Which outside consulting groups were engaged? None.

What off-site leadership programs were managers and supervisors sent to? None.

Then how did it happen?

First, a clear vision was established. Then a small amount of modeling was provided. From there it was all self-organized. We became one of the “Best Places to Work” the same way a baby learns to walk.

Humans arrive on Earth already knowing how to learn.

Exceptional organizations of the 21st Century will come to honor this, get out of the way, and allow self-organized growth to flourish in a natural rhythm that dances to the hum of the universe itself. Every human is capable of learning, leading and evolving given the freedom, safety and flexibility to do so. But for this to occur, leaders of established organizations must show restraint and refrain from making all the rules, inserting excessive structure, and suffocating the insatiable capacity of humans to learn and grow.

Leadership: Dispersed in nature

I was alone one night in the Arizona desert east of Flagstaff when the epiphany arrived. It came in the form of five short words: “In nature, power is dispersed.” I froze in place, contemplating the significance of this knowledge before asking aloud a series of rhetorical questions to the desert itself.

“Where is the capital of this desert landscape? Where is its headquarters? Where are all the managers and supervisors? Which one of these cacti is in charge of all the others?”

The answer to each question was abundantly clear. The leadership power of nature is dispersed. It inhabits all its pieces, big and small, living and non-living.

Humans who are a part of nature, not above it, ultimately aspire to organize in this same way. But for that to happen, our approach to leadership must change.

Think about how a baby learns to walk, and the roles parents do and do not play in that complex learning process. That’s the kind of leadership we need more of.

“Let children wander aimlessly around ideas.” — Sugata Mitra

Thank you for considering my thoughts. In return I honor yours. Every voice matters. Nestled between our differences lies our future.