It is the eve of Winter Solstice, the nadir of a harrowing year. Ordinarily, holiday gatherings would buoy our spirits and tide us through this season of brittleness, when hope itself can seem dormant. But an unrelenting virus now forces us to seek other sources of renewal.

Beyond its devastating physical toll, COVID-19 is causing marked declines in mental health as people struggle with isolation, anxiety, grief and trauma. And these responses might not dissipate, even with the arrival of vaccines.

Mainers face the added challenge of limited daylight and – for some – seasonal affective disorder (aptly termed SAD), which can further darken moods.

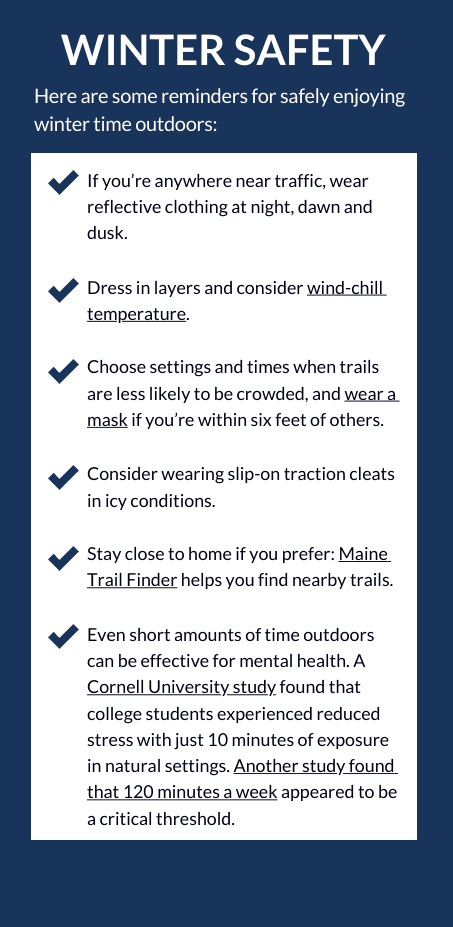

Fortunately, there’s a shining star to guide us through this trying winter: time in nature.

Pandemic deprivations are stimulating renewed interest in being outdoors. The past year has seen a marked uptick in hiking, gardening, recreational fishing and the sort of restorative communing with nature that Norwegians call friluftsliv (pronounced free-loofts-liv), literally the “open-air life.”

Picnicking in the snow

Those pursuits might seem more suited to the height of summer than when daylight dwindles and temperatures plummet. But having lived for a year in southern Norway, where winter days fade after just six hours, I can attest to the sustenance that comes from a culture committed to enjoying time outdoors regardless of weather or season. Norwegians take pride in their affinity for nature and enjoy – by law – a right to roam on undeveloped lands

On one memorable day there, I joined a wonderful retirement-age couple for as much cross-country skiing as the limited light allowed – a ritual that marked many of their winter weekends. At midday we stopped along a frozen lake for an elegant picnic lunch, sitting atop boulders and basking like turtles in the sun. Gunnar and Else taught me that cold need not deter anyone from venturing outdoors, as long as they dress for it – and focus more on the saffron light, snowscapes, wildlife and forest scents than the temperature.

‘Tonic of wildness’

The sensory effects of time outdoors may be key ingredients in what Henry David Thoreau called the “tonic of wildness,” which offers therapeutic effects that extend far beyond the physical and mental benefits of exercise.

Research in Japan, where a growing number of people practice shinrin-yoku (“forest bathing,”), reveals the many ways that meditative woods walks can soothe nervous systems, improve moods, boost immune responses and combat fatigue. This nature therapy practice began decades ago to help urban residents in high-stress jobs who were increasingly depressed, distracted and unhealthy.

Now, in the pandemic, shinrin-yoku is helping people cope with stress and burnout – as in a British Columbia pilot program that will offer remote “forest bathing” sessions to an estimated 10,000 health care workers, starting in January.

Studies in ecopsychology further affirm that when it comes to our physical and psychological well-being, in the words of University of Chicago psychologist Marc Berman, “nature is not an amenity, it’s a necessity.”

We’re fortunate in Maine to have ready access to places where we can walk for free in natural settings. Even in Portland, known as Forest City, there are more than 70 miles of trails. And without summer visitors, physical distancing is far easier this time of year.

Time outdoors need not even be recreational; we can restore ourselves outdoors just as well in chore mode if we’re attentive to place.

Escaping screens

As COVID-19 forces us to confront a scale of human death unprecedented in generations, witnessing the continuum of life, death, decay and regeneration woven through natural systems can be reassuring. Even winter’s freeze-thaw cycles help remind us of lengthening days and the promise of renewed growth.

In her new book, “The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of Nature,” British psychotherapist Sue Stuart-Smith explores the healing power of plants for those suffering emotional pain. Noting how one veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder bonded with a particular tree in his daily walks, she writes that “it is perhaps a natural impulse to take distress and suffering that is hard to articulate and bring it to a form of life that has no need of words.” In the pandemic, many people have found this dynamic at work with household pets, and many more might find solace in trees.

The stressors of 2020 – pandemic fears, political dysfunction, economic losses, doomscrolling and Zoom burnout – have been heaped atop lives already overpacked and far too screen-bound. Our techno-treadmill existence has created what naturalist writer Sigurd Olson called a “restlessness within us, an impatience, which modern life with its comforts and distractions does not satisfy…We may not know exactly what we are listening for, but we hunt as instinctively as sick animals look for healing herbs.”

Long before the pandemic, many people had grown weary of the frenetic pace and 24/7 virtual connectedness that sent stress levels soaring. If some good comes from this catastrophe, it may be that more people rediscover nature’s dependable ability to ground and steady us when the world feels increasingly unstable.

In a strange and hard holiday season, the “tonic of wildness” may be the most valuable and enduring gift we receive.