The concept seems simple. Avoid the impacts of overhead wires, towers and wide corridors by running new high-voltage transmission lines underground in roadways, rail beds and existing utility rights-of-way.

It’s a demand being voiced by many opponents of a proposed 150-mile overhead transmission line from the Houlton area to central Maine, the Aroostook Renewable Gateway. And it’s a technology being used or proposed to varying degrees for three other projects in the region.

But underground transmission lines have their own complexities and costs.

This is a summary of the three other projects in play in New England and New York with buried cables.

Twin States Clean Energy Link

Twin States is a $2 billion high-voltage direct current line planned from Quebec to Londonderry, N.H. It would run along existing transmission rights-of-way and state highways.

The route would include upgrades to 110 miles of existing, alternating current overhead lines, plus 50 miles of new underground lines along highways in Vermont and 25 miles in New Hampshire.

Power flows would be bidirectional based on the region’s shifting seasonal supply and demand needs — south from Canadian hydro dams and north from United States offshore wind projects, for example. Capacity is rated at 1,200 megawatts, similar to the output of the Seabrook nuclear plant.

Twin States has been in the news lately because the Department of Energy selected it as one of three projects nationally to qualify for a federal revolving fund to help pay for transmission infrastructure.

It hopes to start construction in 2026. The lead developer is National Grid, the U.K.-based global energy company that owns utilities in New York and Massachusetts.

Twin States was designed to minimize the strings of wires that many people find ugly and the cutting of trees necessary to make room for the wires. Those visual impacts helped kill the Northern Pass project in New Hampshire in 2017, and greatly delayed the New England Clean Energy Connect line in Maine, which is still under construction.

“What we learned from both is that significant tree clearing was not going to be acceptable,” said Terron Hill, director of transmission network strategy at National Grid.

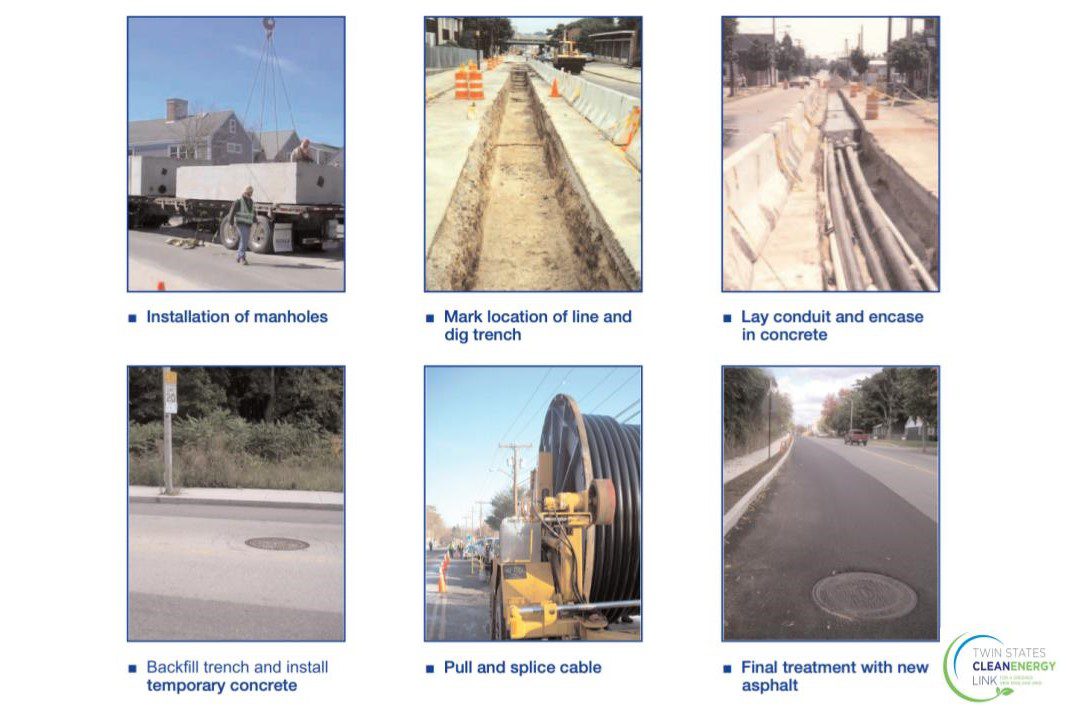

National Grid is still refining its designs, but the roadway sections will involve digging trenches below the frost line, similar to methods used for telecom and water lines. Electricity will move through a pair of six-inch diameter cross link polyethylene cables, heavily insulated wires that are now commonly used in this application.

As explained by National Grid, the cables will run through eight-inch diameter protective plastic conduits. They will be encased in concrete, then backfilled. Cables will then be pulled through the conduits and spliced at access points, with manhole covers in the roadway. The cables will go under the Connecticut River using a trenchless technology called horizontal directional drilling.

National Grid owns an existing transmission corridor that connects in Canada, but Hill said burying cable next to the overhead lines isn’t feasible. The lines cross highways, streams and wetlands. They follow hilly, rocky terrain. Trees would need to be removed to widen the right of way. Access roads would be required on the right of way for installation and maintenance.

Overall, Hill said, underground transmission lines are more expensive than aerial. But he declined to estimate the cost difference, saying it was project-specific based on geography and terrain.

Champlain Hudson Power Express

Champlain Hudson is notable for two reasons. It will be the country’s largest fully buried transmission line when completed in 2026, according to the developer. And after 15 years of planning, it’s actually under construction, with work begun on a converter station in New York City.

Referred to as CHPE (pronounced “Chippy”), the $6 billion project is rated at 1,250 megawatts, enough to serve a million homes. Power will come mostly from Canadian hydro dams.

The direct current line will stretch 339 miles from Quebec to Queens, N.Y., with 140 miles underground mostly along highway and rail corridors, and 190 miles of submarine cable under Lake Champlain and the Hudson River. Cable manufactured in Sweden has been delivered.

“The CHPE project,” the developer said in a news release, “was intentionally designed using buried HVDC cables to avoid disruption to communities along its path while also modernizing the state’s transmission system, and strengthening the grid’s resiliency and reliability.”

CHPE is a partnership that includes Transmission Developers Inc. and Hydro Quebec, the provincial utility that owns massive dams in Canada. Transmission Developers is owned by the asset management firm Blackstone Inc. CHPE declined an interview request from The Maine Monitor.

In an interview earlier this year in E&E News, the co-author of a research paper on the project said the high cost of fully burying the line was key to its approval.

“The costs have increased because they are kind of erring on the side of adopting a plan that will eliminate objections from local communities,” said Ryan Calder, an assistant professor of environmental health and policy at Virginia Tech.

“I think (TDI) has seen that when long-distance transmission has been proposed and they try to ignore or steamroll through local opposition, it can ultimately be canceled.”

New England Clean Power Link

New England is also being proposed by Transmission Developers. It’s similar in capacity to the other two — 1,000 megawatts. It’s also a direct current design with bidirectional power flows.

The 154-mile route would go under Lake Champlain and waterways along the New York border, then underground along roads and other rights-of-way connecting to an existing transmission corridor in Ludlow, Vt.

The $1.6 billion project, which is fully permitted, was an early competitor to bid for clean-energy capacity to meet Massachusetts climate laws.

But Massachusetts chose Northern Pass, which was ultimately killed by New Hampshire in 2017, and then NECEC in Maine, which was then delayed by court battles.

TDI has been trying to advance the project for at least 10 years and sought to put the line in service by 2020.