COOPERS MILLS — A barren flagpole rope clinked in the breeze outside Country Manor Nursing Home on a recent fall morning. It was the only outward sign that the Lincoln County facility, once home to 35 residents, now was deserted.

But visible through a gap in the curtains was a room with a stripped medical bed and an empty cupboard. One of the side doors to the building was held shut from the inside with ropes tied to the wall. An abandoned standing nurses station lingered in the partially-lit hallway.

Country Manor announced at the end of August that it would close due to staffing shortages, declining occupancy and its rural setting. The home had been struggling for years, according to federal data, community members and a previous investigation by The Maine Monitor.

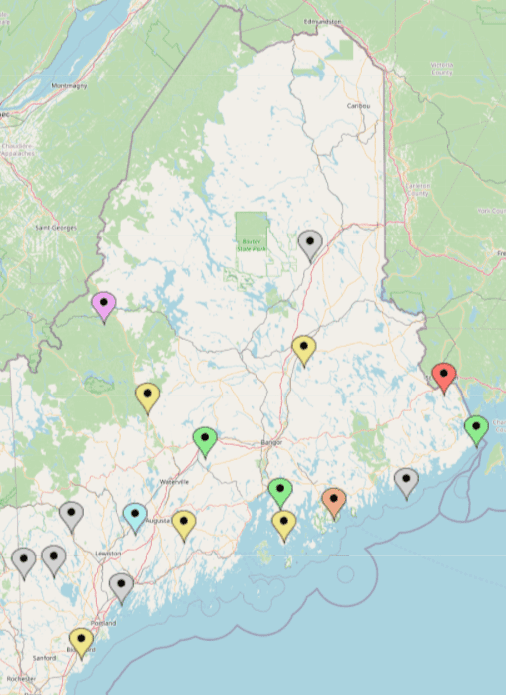

Country Manor is one of five Maine nursing homes and one assisted living facility that have closed since August.

State long-term care experts say they are hopeful Maine won’t have more nursing home closures. But empty, rural nursing homes, coupled with a growing demand for in-home care, could foreshadow a major challenge ahead for a state with one of the oldest populations.

While Country Manor residents have been relocated to other nursing homes, the loss of even a small facility such as this one stretches beyond former residents and their family members. Neighbors say they worry about the loss of jobs, emergency services and community engagement.

“All these closures are symbolic of centralization and impersonalization,” said Chuck Vaughan, who lives across the street from the abandoned facility, in what officially is the town of Whitefield. “Every time they close, you lose something local and something caring.”

Not just an empty building

Chuck and Harriet Vaughan said the unincorporated hamlet of Coopers Mills is a tight-knit place. When they moved to the area 15 years ago, it felt like they had gone back decades in time.

When describing their community, residents returned to a common theme: “Neighbors helping neighbors.”

“It used to be like that all over Maine, and now it’s a dying characteristic of Maine life,” Chuck Vaughan said.

When he heard that Country Manor would close, Vaughan worried the decision would make the community a lower priority for emergency services.

“When you lose something like that, it’s not just an empty building. What will we lose in services attracted to the area because of those facilities?” he said.

Harriet Vaughan said the closure wasn’t a surprise. She followed the facility on social media and said it frequently posted open positions. “It was a revolving door.”

“There was always a shortage,” her husband added. “I think COVID-19 put the nail in the coffin.”

Rising contracted hours

A survey of Maine nursing homes this fall found that 94% experienced staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the Maine Health Care Association, which represents 200 nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

But a joint investigation this summer by The Maine Monitor and The Investigative Reporting Workshop found that many Maine nursing homes were struggling with workforce shortages even before the pandemic. Contracted hours for certified nursing assistants in nursing homes across the state nearly doubled between 2017 and 2020.

Contracted workers, which are hired through outside agencies and can be expensive for facilities to employ, traditionally were used as a stopgap during emergency shortages. They increasingly are becoming the norm in Maine as nursing homes struggle to find qualified candidates for permanent positions.

Four of the five nursing homes that announced they were closing this fall — including Country Manor — recorded among the highest increases in the percentage of their direct care hours done by contracted CNAs during that 2017-2020 period. Many of them cited staffing shortages as a reason for closing.

Country Manor’s contracted CNA hours increased 28% between 2017 and 2020, putting it among the among Maine’s top 10 nursing homes with the largest change in contracted hours.

Angela Westhoff, president and CEO of Maine Health Care Association, said there were many systemic problems that caused these homes to close.

Many nursing homes serve a large number of MaineCare recipients. These patients can have higher needs than in other states, she said, and MaineCare reimbursement rates haven’t kept pace with necessary increases and wages and benefits.

Staffing shortages mean facilities can’t accept new admissions, even if they have beds available, she said. And the pandemic added burnout to an existing workforce problem.

In addition, Country Manor reportedly lost six employees after Gov. Janet Mills announced a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for all health workers.

“Nursing homes are the homes of these residents that they care for, and sometimes it’s decades of their lives so they develop personal relationships with the residents and their family members that come in,” Westhoff said. “It’s a tight-knit kind of community, so of course it’s upsetting when a closure is announced.”

In a small community like Coopers Mills and Whitefield (pop. 2,255), the closure means one less employer in a town that neighbors say doesn’t have a lot of economic opportunities.

And nursing home jobs are disappearing across the country.

A national study from the American Health Care Association last month found that nursing home jobs are down 14%, while other health-care sectors have mostly recovered since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing homes nationally have lost 221,000 jobs during the pandemic, according to the study.

That’s alarming news for Maine, often considered the oldest state, where the need for those jobs is only going to grow, Westhoff said.

“It paints a very dramatic story for the future,” Westhoff said. “I don’t believe that there’s enough beds and space available to cover the needs.”

‘I didn’t like the vibe’

Sharon Clark, whose home faces Country Manor, said she and her husband used to sit on their porch and joke about picking out their rooms in the nursing home across the street.

When her father needed to go into a nursing home a decade ago, it would have been “wicked convenient” to have him at Country Manor. Clark opted instead for a place in Augusta.

“I didn’t like the vibe at Country Manor,” she said. “I think it had gone downhill in terms of the care.”

The U.S. Center for Medicare gave Country Manor one out of five stars — “much below average” — based on health inspections, staffing and quality of resident care measures.

But there are others who praise Country Manor. Another neighbor, Richard Montag, used to walk across the street three times a week to volunteer hosting bingo games and Bible studies. He brought packets of cookies for the bingo winners. It gave him something to do in retirement.

One neighbor said Montag was most impacted by the closure because volunteering gave him a sense of purpose. Montag said the staff did a good job of keeping Country Manor clean.

“I’ve been in lots of nursing homes. There was no urine smell in this one,” he said.

Country Manor shut down tight during the pandemic, Montag said. The community was sad that it never got a chance to really reopen.

Kelley Mank, a neighbor who has cared for an older relative with dementia, said it was hard to see the residents relocated because changes in routine are especially hard on people with dementia or Alzheimers. They have to learn a new place, and often don’t understand why their family members can’t visit as much.

Mank said she wished Country Manor found a different solution instead of closing.

“We should respect our elderly more,” Mank said. “This is a sign of disrespect and not thinking about the people within the walls of the building.”

North Country Associates based in Lewiston, which operated Country Manor, could not be reached for comment.

Relocating residents, especially when they don’t want to move, can lead to more falls or higher rates of depression, said Brenda Gallant, Maine’s long term care ombudsman. The ombudsman program is an independent nonprofit that advocates for residents and investigates complaints on their behalf.

Gallant and her team work with residents after they are notified of the closure to make sure they feel supported and have information. The facility is required to have a discharge plan and cannot close until all residents are placed somewhere else.

Including the five closures this year, 18 Maine nursing homes have closed in all since 2012, according to records from the ombudsman program.

It’s difficult to predict whether nursing homes will continue to close, Gallant said, but she predicts there will be an increase in home care and residential care going forward.

“I think we’ll see more home care (and) probably a greater development of assisted living and residential care,” Gallant said. “But we will always need nursing home care. We just may not have as many nursing homes.”

‘My wife was happy’

Frank Slason used to visit his wife, Diane, at Country Manor every day. It took him 15 minutes to drive there from the home they built together in Somerville.

He had fought hard to keep Diane, now 86, out of a nursing home. But when it was determined that he couldn’t care for her, she ended up staying in a couple of different places. Country Manor was the best of them all, he said.

After more than six decades of marriage, Slason still speaks reverently of his wife’s intelligence, beauty and accomplishment as an equestrian. He recalled with glee the time she trained a horse that bested Caroline Kennedy’s.

“Suffice it to say, 64 years went by like 64 days,” Slason said. “I’ve never had such a wonderful woman in my life and it’s just a wonder I’ve been able to hang on.”

When COVID-19 shut down Country Manor, Slason continued to visit as much as was allowed. Mank, a neighbor, recalled seeing him at the window, waving to Diane inside.

The workers there were “wonderful,” Slason said. But they were overworked, underpaid and unappreciated.

“I’m looking for a word that would describe how people can be so compassionate and loving to people that aren’t their own,” he said.

His wife lived at Country Manor for two years. Then one day this fall, Slason said he was handed a letter that the home was closing in 30 days. It had a list of places for him to choose from.

Slason said employees, some of whom had been there a long time, were just as upset as he was.

“We were all in tears. It happened so quickly.”

Now Diane is 30 miles away at Heritage Rehabilitation and Living Center in Winthrop. He visits her three times a week. But it costs him $20 in gas to drive his truck there each time and the drive is nerve wracking for him.

Diane doesn’t recognize him anymore. But he still reads her letters and shows her old pictures of her and the horses.

But he misses having her close to home at Country Manor.

“I was happy. My wife was happy. I could see her every day.”