This story was originally published by Craftsmanship Quarterly.

Standing beside his 32-foot lobster boat docked near Eastport, Elijah Brice tells me he has saltwater in his veins.

“I just have to get some time on the ocean here and there to be OK,” he says. “It just calls to me.”

These sentiments are expected, perhaps, from someone who has sailed the seas for decades. But Elijah is just 19 years old when he tells me this.

The dockyard in Eastport is quiet this morning. If we listen closely enough, we can hear the ocean less than a half mile from where we circle Elijah’s boat, the Perseverance.

In its past life, the vessel was used for chartered whale-watching tours; today, as he runs his hand along the boat’s bright blue hull, Elijah recalls the 12-hour days he spent at his shop, for nearly a year, stripping the boat’s hull down to the bilges, rebuilding the cabin and the deck, replacing the engine, rewiring the electronics, upgrading the plumbing.

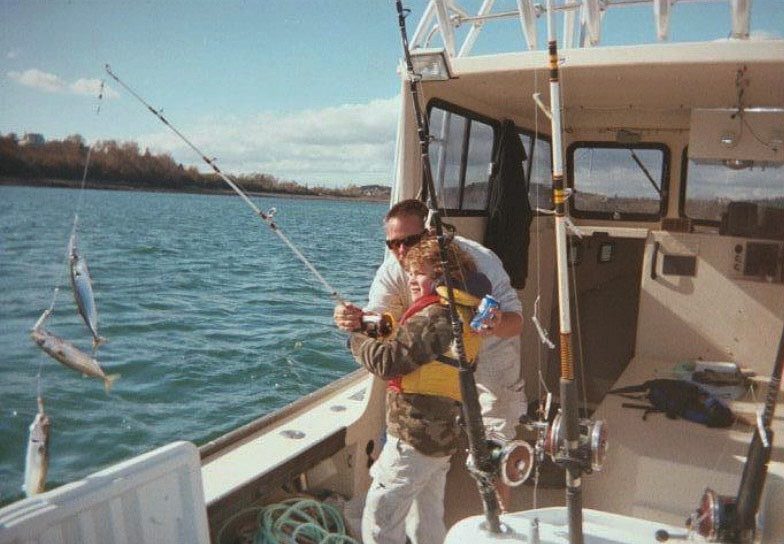

Elijah spent the first decade of his life growing up on Barnegat Bay, just outside of Lavallette, New Jersey, where his grandfather was a master carpenter. During much of that time, his grandfather was working on boats, and he’d invite young, 4-year-old Elijah to help.

“I was a little kid so I could fit underneath the trailer to paint the bottom of a boat,” Elijah recalls.

There was the 14-foot yellow rowing skiff, where he reeled in his very first fish. And the 18-foot Sanderling, where he first fished blue-claw crabs with his father and grandfather. And the Carolina, and the… His list goes on.

In 2012, when Elijah was 10, his life took a surprising turn. His father, Colie, had been considering retiring, maybe somewhere in New England.

His mother, Manuela, was traveling with friends to eastern Maine (“downeast” to Mainers), and instantly fell in love with Eastport, a tiny fishing town with a population that barely numbered 1,300. Entirely smitten, she thought: Why wait?

So, the family headed north to Eastport, the easternmost city in the U.S.

Change in the water

Settling into his new home, and his new spot on the ocean, Elijah headed out to explore Eastport’s working waterfront. He soon got a job working on the Jolly Breeze, a tall ship, doing preseason work to ready the ship to sail. He spent the next summer working at Moose Island Marine, where he met more locals, picked up new skills, and started to make a name for himself. As the rest of that decade unfolded, Elijah learned an array of other maritime trades, all while earning his high-school diploma. But today, Elijah is not sure what’s next. “There’s too much uncertainty in the water,” he says.

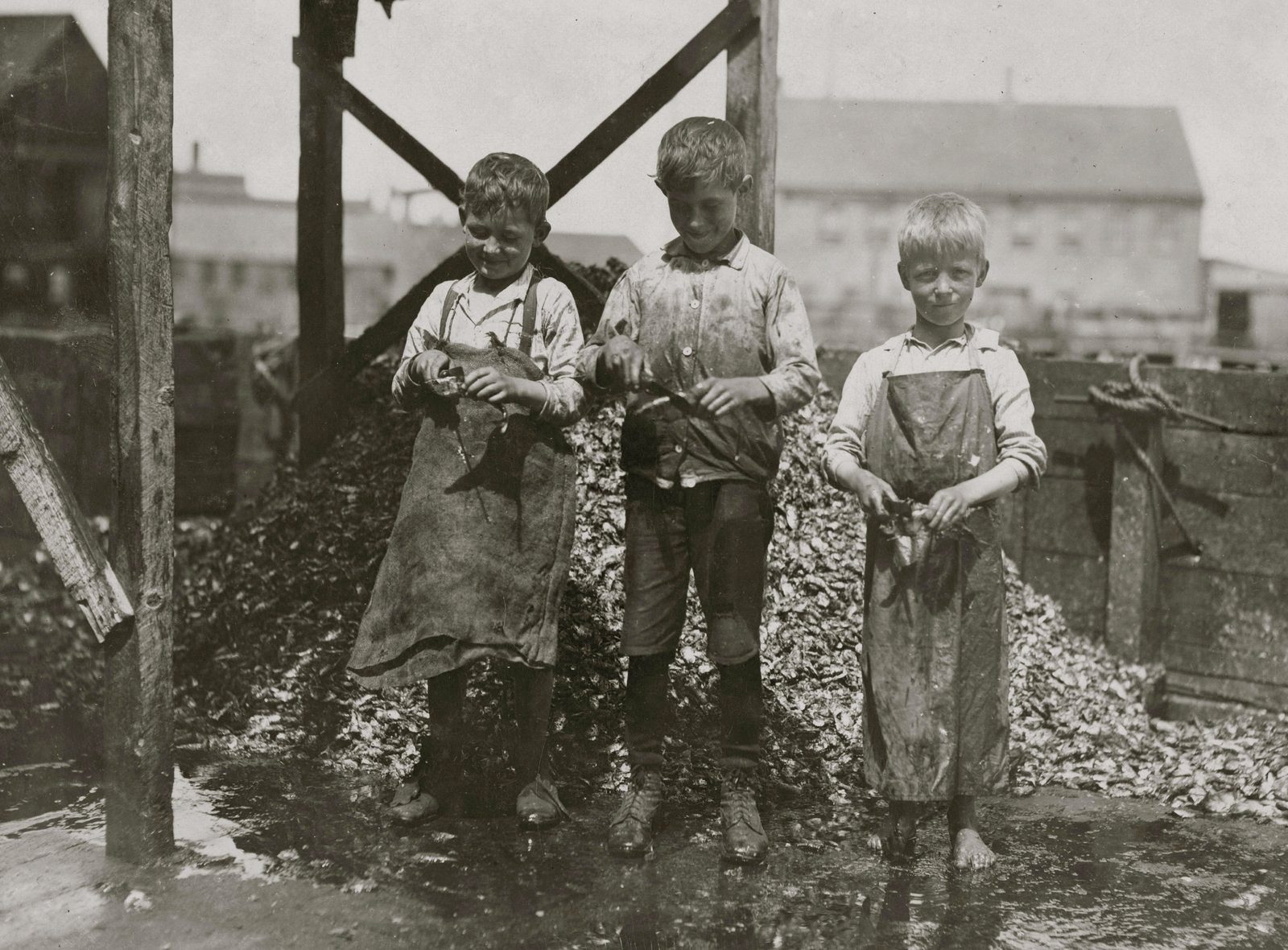

By “uncertainty,” Elijah means the changes coming to fishing the seas, in any form. In some respects, change is no stranger to Eastport’s lobstermen, most of whom are a generation older than Elijah. In 1876, Julius Wolff canned the first sardines in the United States right here in Eastport. At its peak, the town was home to 18 sardine factories and was known as the sardine capital of the world. Over the years, the sardine catch waned, and by 1983, Eastport had shipped its last can of sardines. Yet the legacy and memories spawned by that industry remain strong. Every New Year’s Eve, townspeople gather for their annual Sardine Drop, Eastport’s version of the giant Ball Drop in Times Square, except with an 8-foot wooden cutout of a sardine.

Although Eastport lost its sardine industry, the port is still the deepest harbor in the contiguous United States (only the port of Valdez, in Alaska, is deeper, and only marginally). That — along with the fact that Eastport sits on the farthest-flung edge of the country, where 20-foot tides have battered but never beaten its shores — laces this community with a certain pride, and grit.

Before long, Eastporters found other materials they could sell to the world. There’s wood pulp (shipped in tonnage amounts that reach six figures); at one point, even pregnant cows were exported to Turkey (another story for another day).

It was natural, then, that Elijah, would start casting his nets wide, open to whatever he’ll haul in from the water tomorrow.

A murky future

In 2020, a dip below 100 million pounds marked the lowest recorded levels of lobster catch in nearly a decade. Then, on Monday, Feb. 14, 2022, a reversal: State regulators in announced that one-hundred and eight million pounds of lobster, with a total value of nearly $725 million, were caught in 2021. This was the biggest poundage haul since 2018, $300 million more in value than 2020, and a new record.

Brian Beal, professor of marine ecology of the University of Maine at Machias, believes that 2021 might become more of a new norm than the exception. Warm waters make more lobsters proliferate, and do so earlier in the season. And in the Gulf of Maine, waters are now warming faster than 99 percent of oceans worldwide.

This might look auspicious on paper, but daily life on the docks tells a different story. “The old-timers had it down to a science when the lobsters would be in and when they’d head out,” Elijah says. The reality since he’s been lobstering: “It’s been different each year I’ve been out there.”

But let’s take lobstering one step further. As the oceans continue warming, at some point Maine waters will get too warm for lobsters. Those that migrated north from lower New England states will then push onward, into more habitable waters closer to the Arctic seas. By 2030, according to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, lobster population in the Gulf of Maine will fall 40 to 62 percent.

These mixed signals — a meager catch one year, a bountiful one the next, with both playing out over a dour outlook for the future — leave a young lobsterman like Elijah in something of a bind. Elijah had already traded up to a bigger boat, in an effort to build his business; but a bigger boat means bigger overhead, which demands a bigger catch to support it.

“The more I grow my operation, the more vulnerable I’m going to be,” he says. “The more I invest in it, the more lobster I’m going to have to catch every single year to turn a profit.”

On top of today’s growing climate crisis, there’s another challenge disrupting the lobstering industry: preservation efforts for the endangered North Atlantic right whale. By current estimates, 336 right whales exist in the wild, a finding that led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to set new rules and regulations in the fall of 2021 to prevent further whale deaths. (Editor’s note: After this article was initially published, Congress passed legislation delaying the regulations for as long as six years.)

One potential regulation would limit the number of lines fishermen can drop (these lines can entangle whales). Another requires lobster traps to include ropes with so-called weak points, so an entangled whale could break free. To a lobsterman, all of this means fewer lines cast and a higher risk of losing those they catch, along with their traps.

The new rules would have allowed for higher tech options (“ropeless” traps, GPS systems, and so on), but the new technology is pricey. Traditional traps cost about $200 (or as little as $5 for one that’s used); a ropeless trap runs around $4,000.

Ocean innovation

To Elijah, the solution to all these challenges and uncertainties is to hedge his bets. And the way to do that — given his age, location, and myriad passions — is to branch out. In 2018, he launched a boatbuilding operation called Brice Boatworks. He started by purchasing some 40-year-old molds for lobstering boats, which can remake the region’s classic Eastporter, at lengths of either 17 or 24 feet. The molds show some age, some wear and tear; but, he says, they produce “basically the same boats” built decades ago. “It’s kind of cool, you know, to keep it alive. It’s timeless in a way.”

One upside to owning and operating his own boat shop, Elijah says, is being able to do all the maintenance on his own fleet in-house; another is the opportunity to explore and experiment with new technologies.

Yesteryear’s lobstering boats were put together with little more than wood, nails, and glue; today, Elijah adds fiberglass, which make a boat both lighter and more durable.

One recent customer, who had been lobstering for 40 years from the same boat, now wanted a replacement; he also mentioned that he was 76 years old and still hand-hauling. When Elijah finished building his boat, the lobsterman’s first reaction was that he could now go 10 miles farther out, and fish another 100 traps.

“He’s like a little kid again, he’s all excited,” Elijah told me. “It’s really amazing to be able to build a physical object like that, and to rekindle this gentleman’s excitement about getting into fishing again.”

One day, when Elijah was a young teen working toward his lobster license, he watched a documentary about climate change. The film got him thinking about the future, and the potential of aquafarming. He soon enrolled in the Aquaculture Business Development program, and that led him down the Eastern seaboard and back to study various sea farming operations, from oysters to mussels, kelp, and scallops. Kelp caught Elijah’s attention first. He soon invested in some kelp-farming gear, bought some seeds and a limited-purpose aquaculture license, and launched a kelp farm, under the parent company Mainely Seaweed.

Elijah’s first license, granted in 2017, allowed him to put out a 400-foot line of kelp. The following year, he added another license and another 400-foot line. He now farms kelp from November through April; during these months the waters are cooler, which discourages the growth of biofouling organisms. Per line, Elijah hauls in an average of 2,000 to 3,000 pounds of crop.

His harvest is sold to a Portland-based middleman, Atlantic Seafarms, which only uses kelp sourced and grown in Maine. The company, in turn, provides him with new seeding, which helps keep his overhead low.

Next to his kelp lines, Elijah also has a mussel raft, which he installed in June 2021. Unlike kelp, which is seasonally limited, mussels can be seeded and harvested year-round. A mussel crop can take anywhere between one and three years to mature, so Elijah is still waiting to see what sort of income this venture will yield. But he says he’s seen “great growth so far.”

Elijah’s innovative efforts have also inspired some outside organizations to step in with some help. To offset Elijah’s costs (mussel gear isn’t cheap), and to help advance sea farming science, the Downeast Institute, a research facility on Beals Island, about 65 miles south of Eastport, gave Elijah some mussel seed, in exchange for his crop being used as part of a sustainability study. Funding assistance is being provided by the Sunrise Economic Council, which is part of the Downeast Fisheries Partnership.

But climate change also threatens aquafarming. A stronger-than-usual storm can destroy a sea crop, just as it can a land crop. “You can’t really gauge exact returns until you harvest,” Elijah says. “There’s always going to be crop loss — it just depends how much, and how many variables there were in a given season.”

There will also always be change. And given the unsettling disruptions and challenges that change usually brings, some will always be tempted to fight it. But there are also people like Elijah Brice, who decide to face the future head on, and work with its uncertainties.

At some point, the oceans will undoubtedly test Elijah’s resolve. Will lobstering — along with Elijah’s other oceanic enterprises — continue to boom without a bust, or is the bust lurking just beneath the surface? No one knows, but Elijah seems determined not to leave his future to chance. What he does know is that the ocean is calling to him, and he’s trying hard to listen to it, to learn what it’s telling him, just as others have listened in the past. There’s a long history in Eastport of both staying the course and charting new ones, much the way the tides keep coming in while the ocean’s waters continue to change.

The Craftsmanship Initiative is an organization dedicated to reclaiming craftsmanship’s principles of excellence, beauty, and durability as a pathway to a more sustainable world. The flagship venture of the Initiative, which operates as a non-profit, is Craftsmanship Quarterly, a multimedia publication that focuses on master artisans and innovators whose work informs its quest. The article was also highlighted by Our Towns Civic Foundation, which was founded on the idea that “the sources of American renewal are mainly at the community level.”