State public health nurses are serving new parents and infants in communities across Maine — except in the public health district that serves Indigenous Mainers.

Public health nursing services are important for all Mainers, but especially for communities that historically have experienced worse health outcomes, said Lisa Sockabasin, co-CEO of Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness.

“We do not have home visiting. We don’t have public health nurses. And we, according to many statistics, are some of the folks that have the most generational disparities compared to anybody else,” Sockabasin said.

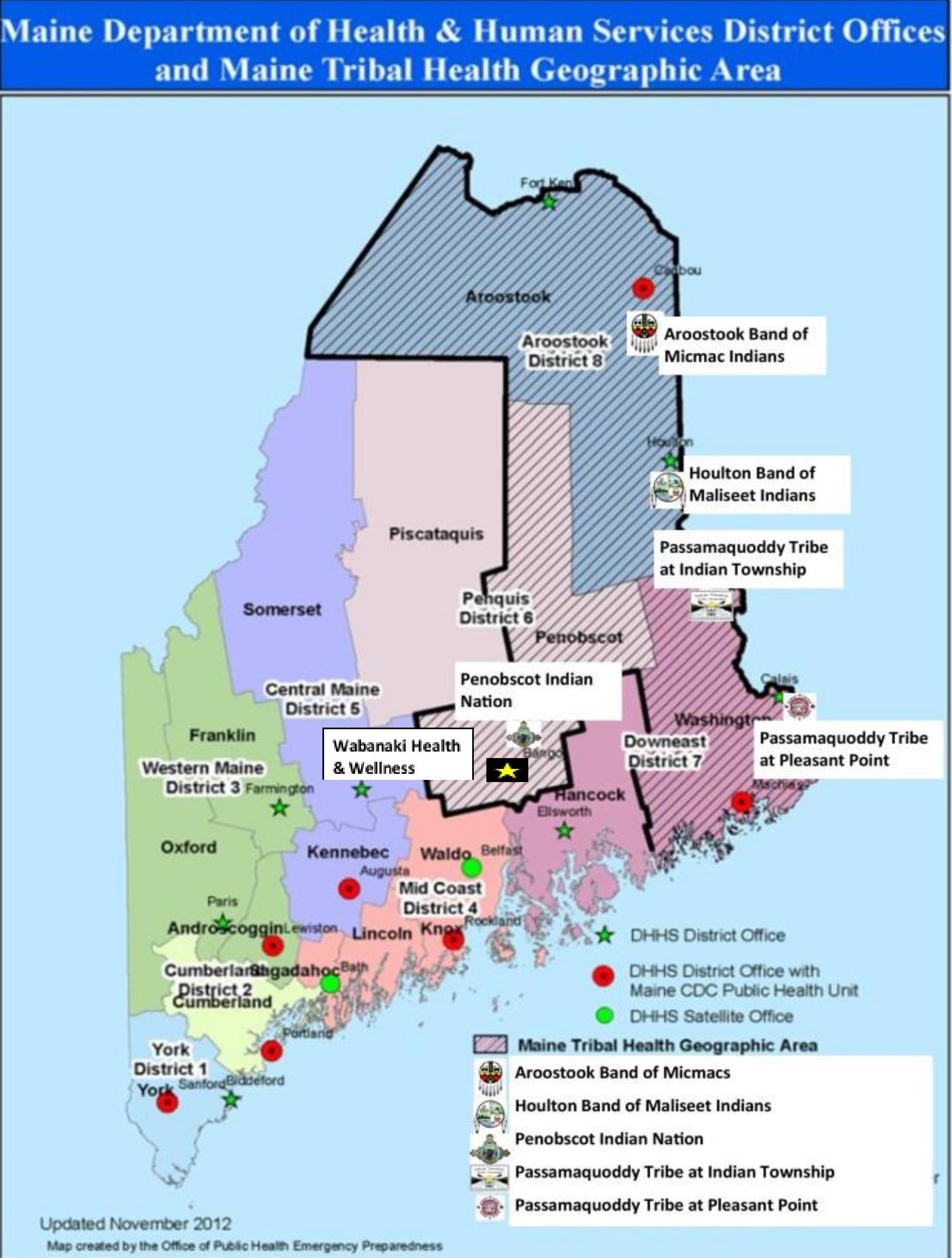

Public health nurses with the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention are stationed across the state’s eight geographic health districts. They visit new parents to educate about safe practices, provide information on preventing illness, administer tuberculosis treatment and respond to infectious disease outbreaks, including COVID-19. Their work often focuses on health challenges that disproportionately impact low-income Mainers.

Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness was added as the ninth public health district in 2011 to represent Maine’s tribal communities, based on population, not geography. But the district never had any public health nurses.

By contrast, as The Maine Monitor has reported, there were 21 public health nurses deployed across the state’s eight other districts at the end of last year.

Tribal communities need public health nurses, Sockabasin said, but “it’s not a one-size fits all.” Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness doesn’t want a nurse from the state deployed to the district, but rather state funding so the district can hire public health nurses who understand and look like the people they are serving.

The public health nursing program has had hiring trouble for years. Only 31 of the division’s 54 authorized positions, including supervisors and educators, are filled. Maine CDC said it has actively recruited, but the pandemic and statewide nursing workforce shortages have made it difficult.

Maine CDC funds a public health district liaison with Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness, and provided nearly $500,000 to support the organization’s health outreach during the pandemic, “similar to services provided by PHNs in other districts,” said spokesman Robert Long.

“Maine CDC shares a commitment to protecting the health of all people who live in Maine, including members of the Wabanaki and other Tribal nations,” Long said. “Public Health Nursing is part of our work toward this goal and serves the entire state, irrespective of the public health districts, which serve as an organizational framework but do not dictate the provision of services.”

Long added that tribal members have received public health nursing services in other districts.

“We will continue to partner with Maine Tribal nations to support their public health efforts as we work to hire additional public health nurses throughout Maine,” he said.

Chief Clarissa Sabattis of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians said she has great relationships with public health nurses in other districts and even reached out to them for help during the pandemic. But it still would be beneficial to have public health nurses serving specifically Indigenous Mainers, she said.

“We definitely don’t have the ability to have a public health nurse that we can just have out in the community,” she said. “(That would help us) be able to reach a lot of our high-risk people or people that maybe can’t go out.”

Services provided by public health nurses are important for new and expectant moms at a vulnerable time in their lives, Sockabasin said. This is especially true for Native Americans who historically have higher rates of poverty and lower graduation rates, she said.

New data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the rebounding national labor market is leaving behind Native Americans. The topline unadjusted unemployment rate among Native Americans in January was 11.1%. The national rate was 4.4%.

Social determinants of health, such as poverty, can impact someone’s access to healthcare, healthy food and safe housing.

“If there are people that are underserved or unserved, such as tribal citizens or tribal community members, then it is the responsibility of public health nursing to have the conversation about who are those most vulnerable people who we are not (serving)” said Sockabasin, who formerly served as director of the Office of Minority Health within the Maine CDC.

Maine CDC said that Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness secures some funding for nursing and other services through federal grants and other sources.

But Sockabasin said her organization only pursued federal funding to have some financial stability without relying solely on the state, which still is obliged to meet the public health nursing needs of all Mainers.

Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness has a budget of more than $10 million that is about 80% federal grant funded and 10% state funded.

There are more than 120 employees, but none are providing public health nursing services.

Asked why public health nurses aren’t in the organization’s budget and workforce, Sockabasin said it pursues funding for a broad range of services. Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness shouldn’t be ignored by the public health nursing program “just because we’re good grant writers.”

“Those resources are allocated to every other district in a way that districts are served with public health nursing,” she said. “We’re asking for the same thing.”

The COVID-19 relief dollars from the state were helpful in addressing Maine’s racial disparities during the pandemic, which at one point was the worst in the country, Sockabasin said. But that funding was distributed among numerous community-based organizations throughout the state and not specifically for public health nursing within the health district.

Maine’s approach to public health needs to involve more resources for community-based organizations led by people of color, immigrants, refugees and tribal people, she said.

“We have to understand that it’s not business as usual when we work with communities,” Sockabasin said. “We have to take our direction from the people who know their communities best. That’s local public health.”