It may not feel like it in Maine right now, amid this stretch of glorious sleeping weather and mild sunny days, but it looks likely that July 2023 will go down as the hottest month humanity has ever experienced.

It was a month of such superlatives, starting in the first week of July, when the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer tool made headlines for showing a stretch of the world’s unofficial hottest days.

“Unofficial” is a key word here — but not because this finding has turned out to be particularly off-base or unreliable. It’s because at a time when science is increasingly caught up in the culture wars — and when denial of climate change is still entrenched for a small fraction of the public (see page 7 here) — experts say the words we use to talk about scientific observations and predictions matter more than ever.

“There’s a difference between … the news story about ‘probably a record’ versus the actual science that goes into the record, which is much more complex,” said Ivan Fernandez, a professor in UMaine’s Climate Change Institute and one of two scientists appointed by the governor to the Maine Climate Council.

The initial news reports on the early July heat extremes were a little muddy on this point. It made for a hectic few days for state climatologist and UMaine assistant professor Sean Birkel, who built the Climate Reanalyzer in 2012 and has been expanding it ever since.

“The whole point of Climate Reanalyzer is, it brings together a variety of weather and climate data sets, and it’s used to explore those data sets — and there’s really not interpretation with that,” he said. “I never thought … that seemingly an innocuous daily temperature page would capture so much attention.”

He said he’s been working to add more public-facing explanation to the site in recent weeks, clarifying what people are looking at when they visit — the sources of the data, how it lines up with tools like Europe’s Copernicus and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate at a Glance, and how it differs from what scientists would consider to be “official” records or observations.

Sensors and physics

Reanalysis, Birkel said, “uses physics paired with real-world observations,” with timely results that “can be very close to reality.” In the UMaine tool’s case, the real-world data comes mostly from NOAA, including sensors on ocean buoys, satellites and observations taken on cargo ships. The physics part is a computer model that’s then applied to fill in any gaps.

“These particular products… are imperfect, but yet they’re valuable, very valuable tools for understanding climate variability,” Birkel said.

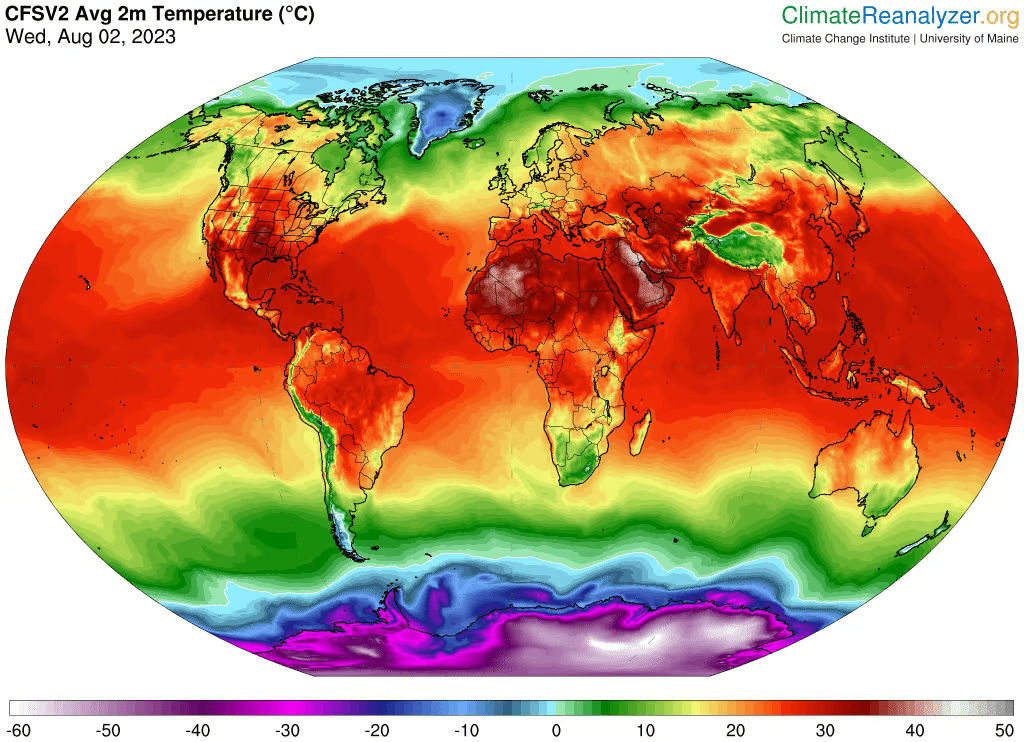

In early July, the tool’s observations-and-modeling cocktail showed average daily global temperatures (as measured in the air two meters above the surface) rising above any other point in a record going back to 1979. As of the start of August, you can see this increase still in effect on the black line.

Birkel explained that a sluggish atmospheric circulation, linked to record-high sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic and the onset of an El Niño in the Pacific, is helping drive this increase. It’s tied not just to the hot weather, but to humidity, wildfires and more.

He said an El Niño that developed from 2015 to 2016 ranked as one of the strongest on record, and since then global temperatures have remained high. The current El Niño is now building up from that historically warm baseline.

Birkel mentioned one other notable factor where scientists are looking into a potential link to the warming — the 2022 eruption of the Tonga volcano, which blasted a huge amount of water into the stratosphere.

Volcanoes have helped fuel short-term climate changes before — the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 precipitated the “year without a summer,” for instance. The lingering haze from eruptions like that is thought to explain the lurid coloring in some famous paintings of the era, such as Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” and various works by J. M. W. Turner.

Shifting baseline

The real-time apparent extremes seen in tools like the UMaine Climate Reanalyzer have legitimate news value, said Ivan Fernandez, despite their “unofficial” designation.

“These interfaces that we humans are using to get an understanding of what’s happening in our world are showing a certain kind of result, and it’s remarkable because it’s really high, it’s really low, it’s really fast,” he said. “And so we pay attention, as well we should.”

Making those records official will require what’s essentially the process of peer review, Fernandez said: Scientists working for groups like the UN’s World Meteorological Organization will assess the data sources that show the new extreme, look at any “artifacts” or outside factors that might have “compromised” the result, and try to validate or replicate it with other techniques.

“When the numbers are slightly different when you actually look in the record books, (that) is simply the process of science taking place,” Fernandez said, “and that’s really good that it does.”

The validation process for long-term climate records can include comparison going back tens of thousands of years, using chemical signatures found in cores of sediment taken from under lakes and oceans, ice cores from the Arctic, Antarctic and other glaciers, and tree rings.

“I would argue it’s not as much of a concern that we broke a record,” Fernandez said, “it’s that we’re breaking more records more frequently, which tells us the whole system is adrift.”

The upshot, Fernandez said, is that Mainers should savor this week’s cool summer temperatures while they last — because “we’re on the cool end of the 21st Century.”

“The hype over ‘what are we going to do about it,'” he said, “is about … let’s stop continuing this pathway. But we haven’t gotten there yet.”

He thinks continuing to repeat and better understand this steady march of new extremes will help people face climate reality and galvanize their communities to make big changes — because, he said, humans’ role in this complex system is one variable we can control.