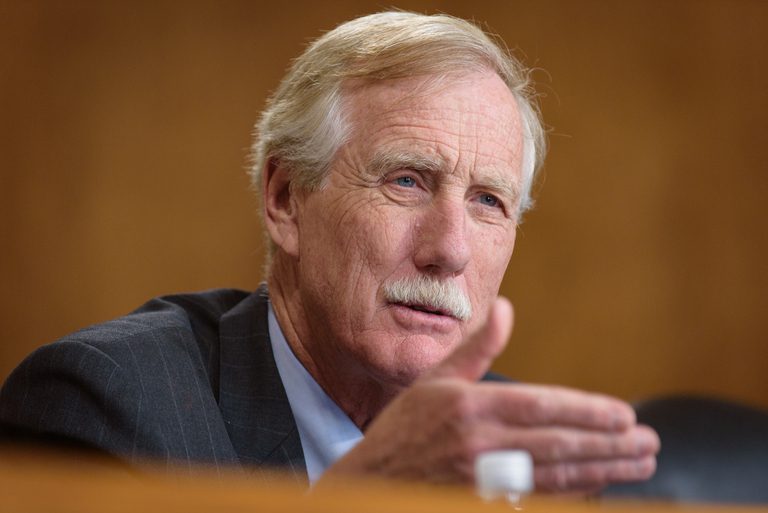

Independent Angus King, running for the U.S. Senate, could benefit from the special circumstances that sometimes work for non-party candidates in Maine.

In recent decades, the state has elected two independent governors and almost did so again in 2010. The state seems to be unusually favorable to candidates running without a major party label.

What are the factors that can be exploited by independents?

First, the independent should run for an open seat. When independents Jim Longley in 1974 and King in 1994, both winners, and Eliot Cutler, the near winner in 2010, ran for governor, no incumbent was in the race. When independents ran against sitting governors in 1986 and 2006, they lost.

By stepping aside this year, incumbent Republican Sen. Olympia Snowe created an opportunity for an independent.

Second, at least one of the two major party candidates should be likely to have limited appeal. In the 1974 governor’s race, Republican Jim Erwin could only muster 23.5 percent of the vote. Twenty years later, Susan Collins, the relatively unknown Republican candidate, also lagged, gaining only 23 percent. In 2010, Democrat Libby Mitchell, winner of little more than third of her party’s primary votes, collected only 19.2 percent in the general election.

This year, King, who was twice elected governor, faces a field of relative unknowns. Among well-known possibilities, all Democrats, U.S. Representatives Chellie Pingree and Mike Michaud and former Gov. John Baldacci chose to stay out of the race. Thus, King is by far the best-known candidate, at least at the outset.

Another possible candidate who decided not to run is independent Cutler. He has remained visible since his 2010 run, pushing a moderate agenda just as has King. Instead of running, he endorsed King and used his email list to promote King’s candidacy. It would surprise no one if King returned the favor two years from now, assuming that Cutler again runs for governor.

If King starts with such a strong advantage based on electoral history and name recognition, why have six Republicans and four Democrats thrown their hats in the ring?

Lightning could strike. King could make a major error or some new information about him could prove unexpectedly embarrassing. And a candidate’s health is always a background factor. If the front-runner falters, the chances for other candidates improve.

More likely, the Republicans are looking forward to a future governor’s race. If a candidate loses an election, but comes across as solid and serious, he or she may capitalize on favorable public opinion in a later race. Collins, the weak GOP candidate in King’s 1994 victory, was elected to the U.S. Senate two years later.

All three of the constitutional officers – Secretary of State Charlie Summers, Attorney-General William Schneider, and Treasurer Bruce Poliquin – are in the GOP field and stand to gain a lot more recognition from the race, thus positioning themselves for a later primary run for governor.

There may also be a stealth reason for a couple of the candidates. There is a woman in each primary, seeking to run for a seat being vacated by a prominent woman. President Barack Obama is expected to make a major effort to bring out women voters this year, and if gender matters in the Maine race, that factor could improve the chances of either woman, both state senators – Democrat Cynthia Dill and Republican Debra Plowman.

While King can use his independent status to gain office, he is likely to get less out of it in the Senate.

King says he wants to caucus with either party depending on the issue. That has not usually been allowed, because party caucus meetings deal with strategy as much as substance and often with more than a single issue. In practice, as Sen. Snowe found, the GOP demands strict loyalty across the board. The Democrats are less likely to discipline mavericks by denying them good committee assignments.

When it comes to deciding which party will control the Senate agenda, King would have to caucus with one party or the other, wielding a vote that could tip the balance, or lose any influence and probably forego good committee slots.

When Oregon Republican Sen. Wayne Morse, quit his party in 1953 to be an independent, he placed a folding chair in the aisle between the two parties. That gesture was short-lived, when he was stripped of key committee assignments. He only recovered influence when he later became a Democrat. The two Senate independents now in office caucus with the Democrats.