Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

Time flies when you’re having a climate crisis. Late last week, the Maine Climate Council marked two years of “Maine Won’t Wait,” announcing a new round of community climate adaptation grants as they did so.

Officials also touted a new dashboard where folks can explore a map of projects, initiatives and installations the state has pursued toward its climate plan, and click around to see data about progress toward our climate goals. Never one to pass up a chance to crunch numbers, I thought we’d spend this week breaking down some of those numbers and assessing the long road ahead.

Maine’s topline goal is to be carbon-neutral by 2045, with stops along the way: “Reduce gross emissions 10% by 2020, 45% by 2030, and 80% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels,” according to the Climate Council website. We now have data on our emissions through the end of 2019, and we’ve more than achieved that first goal for 2020.

Maine’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 were about 25% lower than in 1990, according to the latest state data. This is “primarily due to decreased use of fossil fuels,” the state said in a July report, both by businesses and individuals — Maine’s population increased 9% between 1990 and 2019, while emissions per capita dropped by nearly a third.

Overall, the state projects that Maine will meet its 2045 goal, though it notes that emissions will have to begin to decline a little faster to get there on time. Right now, officials say Maine is 75% of the way to carbon neutrality, meaning that 75% of our emissions are “offset by sequestration in the environment.”

The fine print (again, in that July report) shows this is defined largely by how much carbon is stored in Maine’s abundant forests, compared to how much we actually emit. You can see how our high concentration of forestlands puts us at an advantage by this definition.

Carbon neutrality, or the idea of “net zero emissions,” is in fact something of a controversial buzzword among climate wonks. “In principle, the idea of net-zero offers countries and companies [and states] flexibility in meeting climate goals. But in practice, critics say that net-zero pledges delay meaningful reductions in greenhouse gases and provide cover to those unwilling to take immediate steps to limit emissions,” wrote Umair Irfan for Vox last year, with international net-zero pledges in the spotlight at that year’s “COP” gathering.

The potential for a government or corporation’s net-zero pledge to amount to “greenwashing” depends on how that pledge is defined and approached, argued a paper from researchers at the University of Oxford in December 2021. A meaningful net zero goal, they said, prioritizes comprehensive emissions cuts and an equitable climate transition, among other things.

Maine is still developing the data and approaches it uses to quantify the “carbon sink” side of its plan, so stay tuned on that. But on the “carbon emissions” side, we have many detailed goals we can look to as examples of the kind of “front-loaded” approach the Oxford paper supports — one where policy efforts move to rapidly cut emissions without waiting to meet those carbon sinks in the middle.

Bottom line: The fuzziness of “net zero” is all the more reason to scrutinize specific targets like electric heat pump installations, which Maine has prioritized primarily to offset its top-in-the-nation reliance on heating oil — a dependence that underlies the fact that our residential sector remains an unusually large source of emissions relative to most states, data shows.

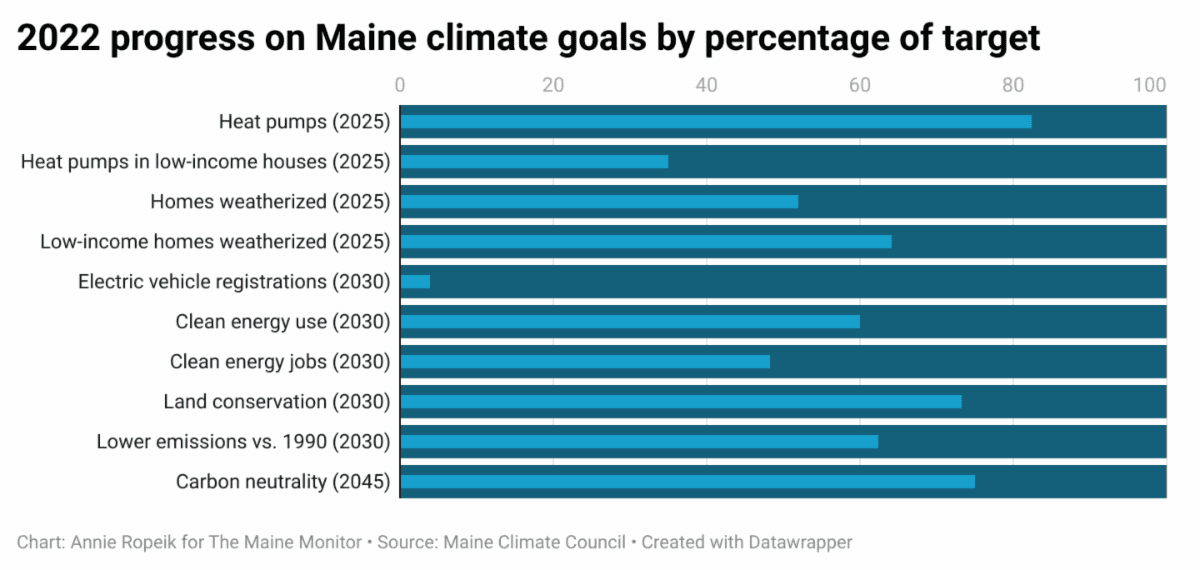

After playing with the state’s new dashboard for tracking targets like this, I still felt in need of a unified, clear visual. I put the state data into a spreadsheet and converted our progress into percentages, which are a simpler way to see areas where we’re doing well and others where we’re behind:

You can see a clear outlier: Our progress on electric vehicle adoption has barely begun, but that’s expected to change in the coming years — a big “if” — as new, cheaper models roll out and chargers become more widely available.

Note that the state offers some interesting maps at that link and in other sections of the new dashboard (scroll down on each goal’s page). One shows how Aroostook County has fewer than 100 EVs registered, whereas EV adoption is more concentrated in Southern and coastal Maine, where chargers are relatively more prevalent and median household incomes are higher.

You can also see, in my percentages above, that we’re doing great on heat pump installations overall, but not so good on making sure those heat pumps benefit low-income households. This is all a form of climate justice, or lack thereof.

“We want to make sure low and moderate-income houses are contributing as well,” Efficiency Maine director Michael Stoddard told WMTW. “They don’t have as much disposable income so we’re changing these [rebate] programs to make it easier for those households to access it.”

It’s important that Maine has goals like this at all, as those Oxford researchers noted in their paper on what makes a good net-zero goal. This particular metric suggests there is more work to do (and more scrutiny needed by folks like me!) to ensure the state’s signature heat pump push is rolled out equitably.

To that end, you can click to learn about Efficiency Maine‘s many rebates for heat pumps, EVs, weatherization and more — including up to $100 for anyone, even renters, to buy DIY winter prep materials like window wraps, pipe insulation and caulk, through Dec. 31.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Visualizing Maine’s progress toward its climate goals.

Reach Annie Ropeik with story ideas at: moc.l1752911006iamg@1752911006kiepo1752911006ra1752911006.