On a Friday in mid-September of 1999, fishermen off the coast of a small rocky island in northern Norway, at the edge of the Barents Sea, saw something that hadn’t been observed in those waters for more than 400 years: a North Atlantic Right whale, its back marked by a large white scar and its body scattered with orange cyamids, a type of parasite that indicates poor health.

An observer snapped a photo and sent it across the Atlantic, where researchers at Boston’s New England Aquarium confirmed that the mammal was indeed a Right whale, and one they’d seen before, known as “Porter,” or no. 1133. (Readers in Maine will likely be familiar with the species for its role in a years-long controversy over fishing gear and whale entanglements.)

Movements of the North Atlantic Right whale are typically very predictable – they travel from Florida in the winter to the Bay of Fundy in the summer (not unlike some of their human counterparts), stopping to feed along the way. Porter had most recently been seen in late May off Cape Cod. His migration to Norway — more than 3,500 miles — was highly unusual, the longest ever recorded for a Right whale.

The stretch of coastline that Porter visited (he stayed for several weeks before eventually returning to Cape Cod) was the site of historical whaling grounds, where the animals once traveled to feed before they were hunted nearly to extinction (there are thought to be only 340 Northern Right whales left in the world).

Scientists believe Porter’s long, unusual journey, so far from his normal route, was either a wild coincidence, or, possibly, the result of stories, passed down through generations, that prompted him to go to where his ancestors had been killed, said Brian Skerry, an award-winning photographer and explorer with National Geographic who spoke about whale culture at the Schoodic Institute on Tuesday evening.

“These were dyed-in-the-wool, very traditional scientists, not prone to hyperbole or conspiracy theories, but that’s what they concluded” was most likely, said Skerry, speaking to a packed room.

Skerry spent three years documenting whale culture around the world, work that eventually became “Secrets of the Whales,” a series on Disney+, as well as a National Geographic cover story and a book. The talk on Tuesday was part of Schoodic Institute’s Summer Lecture Series (the next talk, “Music and Nature Reflections with Hawk Henries,” is Sept. 12).

Skerry has spent 12,000 hours underwater, documenting the world’s oceans — he’s currently at work on a piece about coastal kelp forests in the Gulf of Maine, set to be published next June. Many of those hours have been spent documenting whales, an interest he developed in part after hearing about Porter’s lengthy Atlantic crossing.

Humans have always been fascinated by whales, Skerry pointed out. Whale watching is a $2 billion a year industry. But it was only recently that scientists began to realize that whales, like humans, have culture — behaviors and customs that differ depending on upbringing and location.

“Behavior is what we do, culture is how we do it,” Skerry explained. Most humans use utensils, but we may use forks or chopsticks, depending on where we were raised. Whales, like humans, gather in groups according to language or dialect and prefer certain foods.

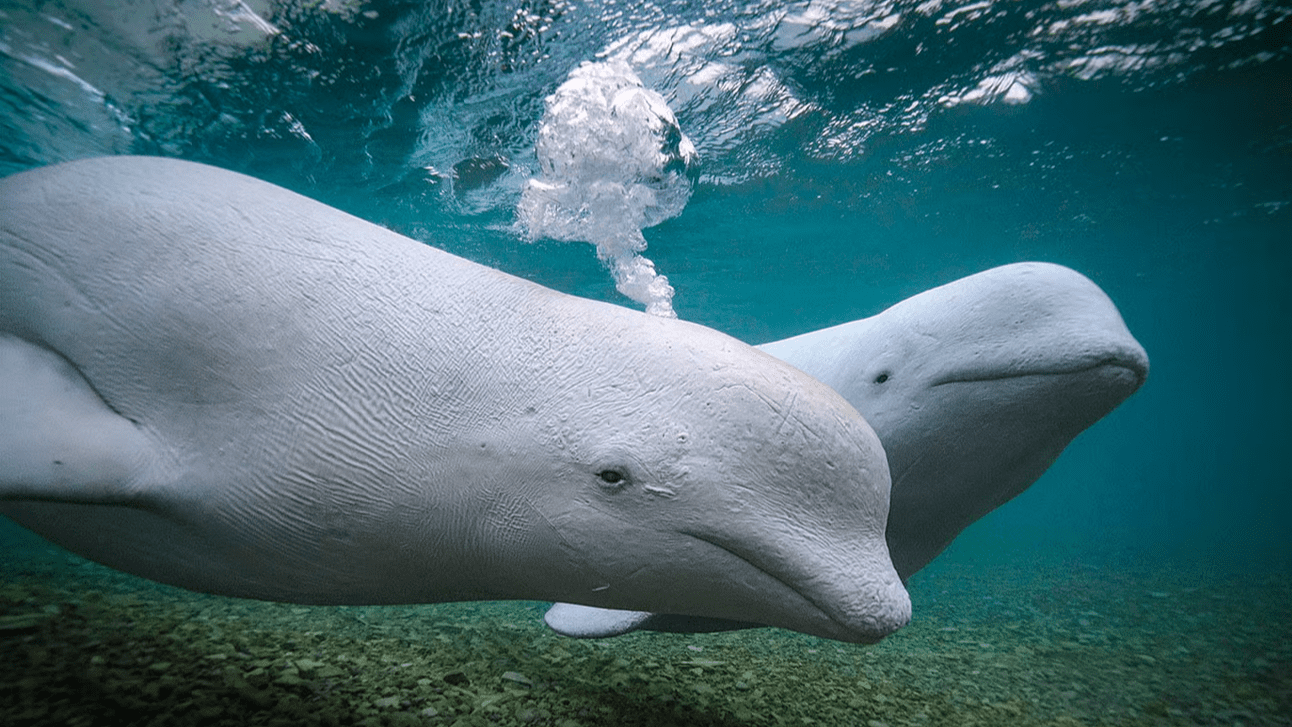

Some, like the Beluga whale, take vacations at their favorite beach (although in this case the beach is above the Arctic circle, hardly my idea of a relaxing vacation), or have singing competitions, like the Humpback.

“The winning tune that gets adopted by all other whales and passed on to the entire Pacific ocean,” said Skerry.

Skerry, who set out more than 20 years ago to make beautiful images of nature, said he now aims to broaden the way humans see the natural world, particularly our brethren living below the surface of its waters.

Our oceans are dying, said Skerry. “We’ve taken 90% of the big fish out of the ocean in the last sixty years. We have destroyed half of the world’s coral reefs. We dump 18 billion pounds of plastic into the ocean every single year” and expel so much carbon into the atmosphere that we have changed the ocean’s chemistry.

Skerry his hope is that people take from this series “those things that we already know — that nature is precious, wonderful and fragile… a place where other families live, families not so different from our own.”