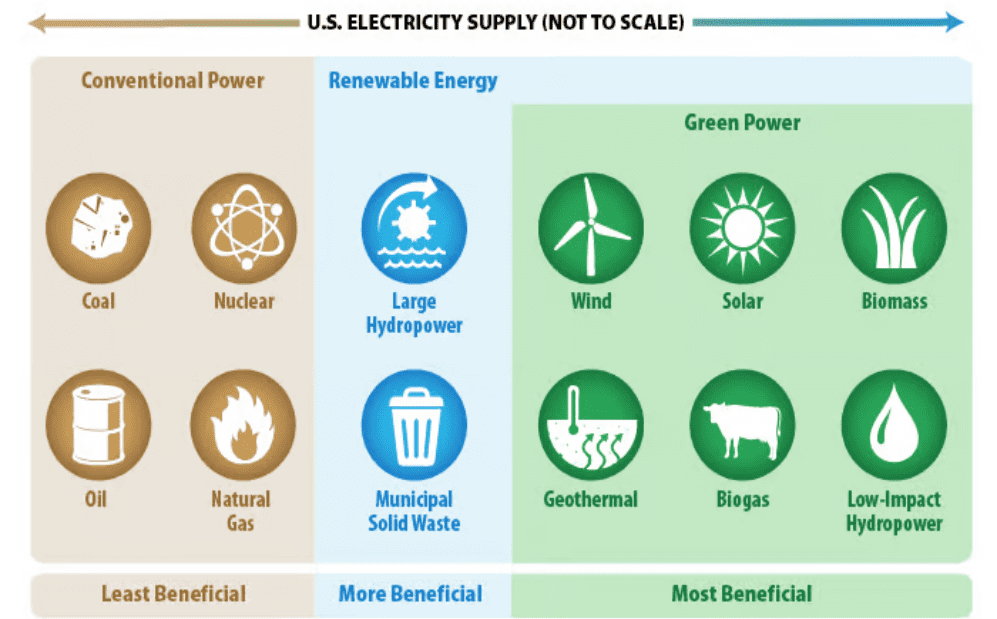

Renewable energy. Clean energy. Green energy. They’re terms we use all the time in the energy and environmental media ecosystem, often interchangeably.

But they have different meanings, and with movements afoot in various states to change definitions to include (or exclude) certain generators to meet clean energy goals, we thought it would be worth it take a look this week at how Maine and the federal government define these terms.

In Maine, a renewable resource is defined as one that’s “capable of being reproduced, replenished or restored following the use of these resources and resources that are inexhaustible.” Maine considers biomass, wood, water, waste, certain kinds of solid waste, solar and wind energy to be renewable.

The Environmental Protection Agency defines renewable resources as “fuel sources that restore themselves over short periods of time and do not diminish,” which include sun, wind, moving water, certain kinds of biomass, and geothermal energy.

What counts as “clean” is a bit squishier. The EPA and the Department of Energy don’t define the term, which is often used in the same breath as “renewable.” For those who do draw a line, most consider consider energy to be “clean” if it is produced by a generator that doesn’t emit carbon as it produces electricity.

Under that definition, a fuel can be clean without being renewable — solar, wind and water are typically thought of as both clean and renewable, while nuclear is clean (in that it doesn’t emit carbon) but not renewable.

California, which does make a distinction, has adopted a “clean energy standard,” which requires the state to source all of its electricity from renewable energy and zero-carbon resources by 2045. (Sixty percent of that must be both clean and renewable.)

Maine statute does not make a distinction between the terms, but does say that renewable energy does not include nuclear, coal and oil.

“Green” power is considered by the EPA to be a subset of renewable energy, representing technologies with the “the greatest environmental benefit.” Coal, oil, natural gas and nuclear power are considered the least environmentally beneficial, while solar, wind, biomass, geothermal, biogas and small-scale hydropower are the most beneficial. Burning trash and large-scale hydropower fall between the two extremes.

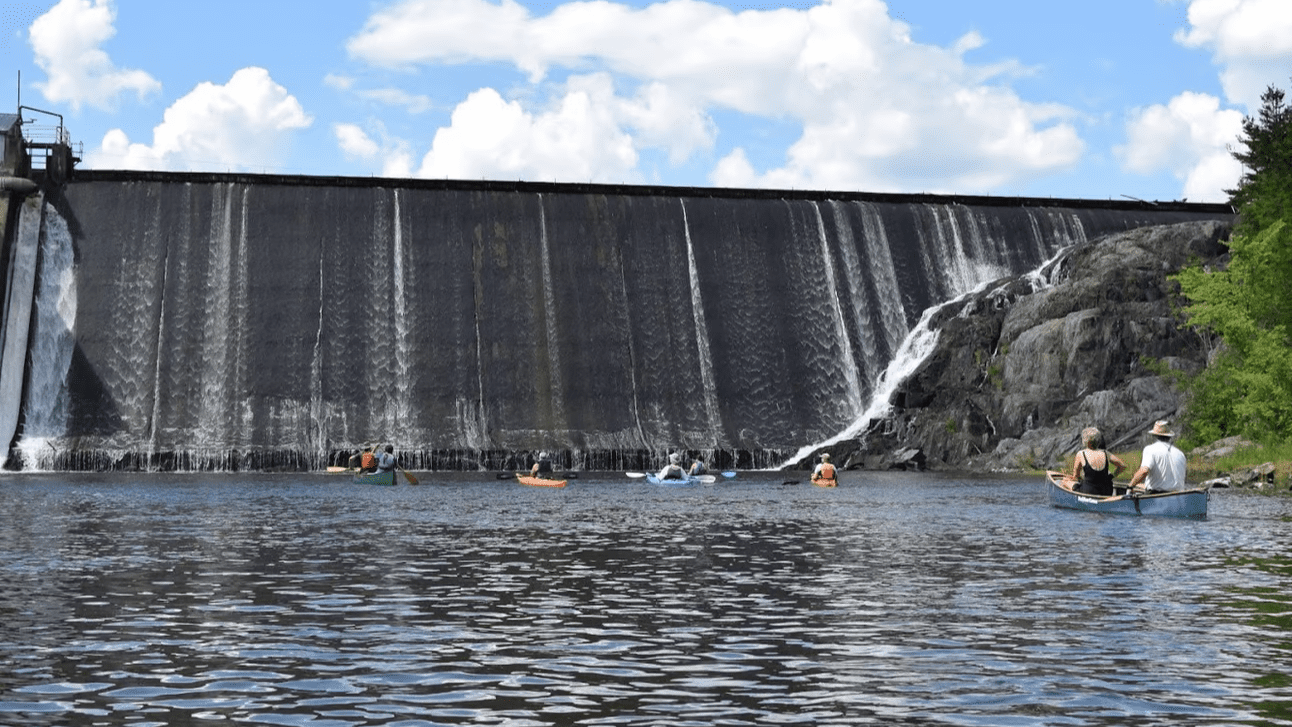

Maine does makes a environmental distinction between small and large hydropower plants, generally allowing only smaller ones (less than 100 megawatt) to count toward the state’s renewable energy goals. That limit was imposed to prevent a few large generators from satisfying all of the state’s renewable targets and to encourage a diverse set of resources, which lawmakers thought would protect jobs, former State Sen. John Cleveland told Maine Public in 2019.

Proposals to raise the cap (which does not apply to wind and solar) and allow larger hydropower projects to qualify, including one this past legislative session, have repeatedly failed.

The EPA, for its part, does count large-scale hydropower as renewable, but caveats that the building of reservoirs dramatically alters landscapes, affecting the people, fish and other animals that rely on the waterways being diverted.

Vermont (which relies heavily on Canadian hydropower to meet emissions targets) and Massachusetts (which is also looking to source more electricity from Canada’s dams) both consider large-scale hydropower to be a renewable resource.

Opponents of adding large-scale hydropower to the list in Maine also point out that building new reservoirs emits greenhouse gases. But those reservoirs can also store carbon, and researchers do not yet have a good answer for how the carbon footprint of a creating a reservoir compares to the same area if the reservoir had never been built, according to the Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, a division of the U.S. Department of Energy.

As states bump up against goals to source more clean energy, some are expanding (or narrowing) their definitions of what counts.

In New Hampshire, there’s a movement to add nuclear to the list, a plan first outlined by the state’s governor in 2018 (more than half of New Hampshire’s in-state electricity generation comes from the Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant).

While nuclear power isn’t considered renewable by most states or the federal government, nuclear plants consistently generate large amounts of electricity without adding carbon to the atmosphere. That’s been winning them new converts in recent years, although there are still concerns around the disposal of nuclear waste and the expense of building new plants or keeping old ones in service.

The proposal in New Hampshire, which is set to be introduced in 2024, is facing pushback from environmental advocates, who say it would hurt solar developers by allowing nuclear plants to access the same subsidies.

Biomass is another controversial energy source, with long-running arguments and conflicting studies over whether the burning of products derived from cutting down trees is better or worse for the environment and the atmosphere than leaving them in the ground.

In Maryland, advocates have been petitioning for years to remove biomass from the list energy sources eligible for renewable subsidies in that state. Meanwhile, Virginia and Arkansas are heading in the opposite direction, declaring increased support for the fuel this year.

Maine, which gets about 1/5 of its in-state electricity generation from wood-derived products, has long supported biomass, with U.S. Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King leading past efforts to declare the fuel carbon neutral.

Speaking of electricity, don’t miss this piece from my co-newsletter writer Annie Ropeik on Maine’s efforts to use money from the Inflation Reduction Act to get heat pumps to more people, especially in multifamily housing.