If you scrolled through your Facebook feed in mid-April, you might have seen four different headlines describing how and why the Maine Legislature adjourned without finishing its work.

Two were fairly similar: “Partisan sparring in Maine House drags into Thursday morning” in the Bangor Daily News, and from the Portland Press Herald: “From Medicaid expansion to pot sales, partisan stalemate in Augusta leaves key issues unresolved.”

But the other two headlines struck a decidedly different tone: “Adjournment fiasco underscores dysfunctional legislative session” in the Maine Wire and “Republicans shut down legislature in attempt to delay Medicaid expansion, cut minimum wage” from the Maine Beacon.

Why the discrepancy?

Fueled by what they see as gaps in political news coverage by the state’s mainstream media, two advocacy groups with strong interests in promoting their agendas are operating websites that look very much like those affiliated with traditional news outlets.

Professors and pundits say the phenomenon is not new — before World War II, newspapers often had a particular ideological bent. The difference now, though, is that professional-looking websites and dynamic social media strategies allow such publications to expand their reach far beyond the neighborhood newspaper stand.

It also increases the possibility that readers scrolling through their social media feeds might not understand that what they’re reading wasn’t produced by a journalist.

Rick Edmonds, a media business analyst at The Poynter Institute for Media Studies in St. Petersburg, said that while advocacy groups have traditionally issued white papers and lobbied lawmakers, the technology now exists for them to produce news-like content, too.

“It’s not terribly surprising, but yeah, I think there’s potential for confusion,” he said.

Following the advent of Fox News and MSNBC, it makes sense that Maine-run sites such as the conservative Maine Wire and progressive Maine Beacon would take advantage of the public’s desire to seek out news that fits with their particular ideology, said Jim Melcher, political science professor at the University of Maine at Farmington.

“The people who subscribe know what they are getting,” he said. “A lot of what both of them do is critical journalism, where they are attacking the other side.”

The Maine Wire, a product of the conservative Maine Heritage Policy Center, has been around since 2011. The Maine Beacon, which focuses on issues important to the progressive Maine People’s Alliance, began publishing in 2016. It’s difficult to gauge the impact of the sites because no unbiased third party tracks statistics about their reach.

A spokesman for the Wire said the website reaches 30,000 to 50,000 readers a month while the Beacon boasts that, on Facebook, it is the most-shared political site in the state.

Both say they are careful to label their content so readers know where it comes from, but when a story pops up on Facebook or Twitter, it’s often hard to tell the difference between which comes from a mainstream outlet and which doesn’t.

“Those are acutely partisan advocacy groups,” Cliff Schechtman, executive editor of the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, said in an email. “They promote propaganda. And they have a constitutional right to do it. But let’s not equate independent journalism with political advertising disguised as news coverage.”

Lance Dutson, who founded the Maine Wire when he served as executive director of the Maine Heritage Policy Center, said while he once railed against the mainstream media, he’s now concerned that people are losing the ability to agree on a common set of facts to serve as a baseline for discussion. In an April column in the Bangor Daily News, he wrote that he was “terrified of this new media landscape.”

“I definitely think there’s an erosion of that baseline,” Dutson said during an interview. “It’s hard on an individual level to chastise it, but on a macro level, it’s definitely causing a problem.”

The difficulty for people on one side of an issue to talk to the other plays out every day on social media channels, at the Statehouse and in the halls of Congress. Without a common understanding of major events, “dialogue seems extremely difficult,” said Melcher, the UMaine-Farmington professor.

“A lot of it is people aren’t watching the nightly news anymore,” he said.

One reason for that is today’s deep partisan divide and how the public views the news media.

An April poll conducted by Quinnipiac University found that 51 percent of Republicans feel “the news media is the enemy of the people” rather than an “important part of democracy.” Among Democrats, only 3 percent picked “enemy of the people,” while 91 percent chose “important part of democracy.”

The Maine Wire

Dutson, who is now a political consultant with Red Hill Strategies, said he launched the Maine Wire because he was frustrated that the mainstream media wasn’t writing about the Maine Heritage Policy Center’s research on topics such as healthcare and welfare.

“The real core reason for creating the Maine Wire was to provide pressure on the press,” he said. “By engaging in the process, we hoped it would swing the coverage back to a more balanced place.”

That underlying feeling that the mainstream media is biased against conservatives still exists today, seven years after the Maine Wire launched, said Matthew Gagnon, the Maine Heritage Policy Center’s current executive director.

“You’re filling a need and a desire in the market for news delivery that a lot of other outlets aren’t, particularly given our perspective,” he said. “To the everyday conservative, there is no option to read anybody who thinks like them when you are reading the Bangor Daily News, the Sun Journal, the Portland Press Herald or any of the other outlets.”

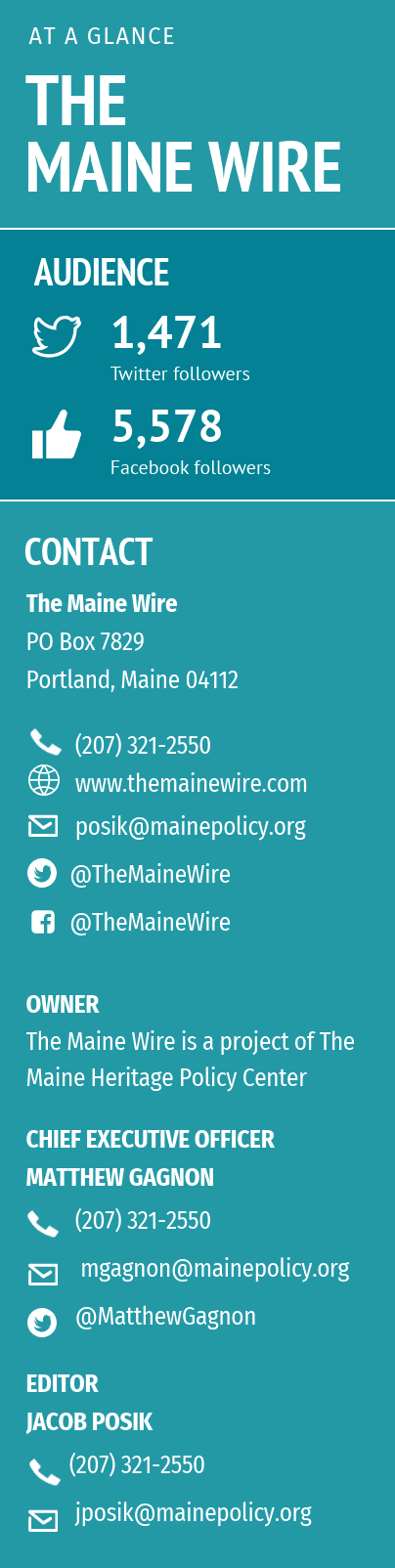

The Wire now features regular opinion articles by a stable of three dozen conservatives, including Gov. Paul LePage. Jacob Posik, a policy analyst at the center, writes more traditional articles for the site, although The Wire has pulled back on in-depth reporting, Gagnon said.

One piece that seemed to catch on with readers was a plea to end the state’s vehicle inspection sticker requirement, which drew 60,000 views in 48 hours, said Posik, a recent University of Maine graduate who worked on the student newspaper for four years. A recent Posik story arguing for the state to abandon its proficiency-based diploma system drew 4,000 views in 24 hours, he said.

As to whether readers might confuse the Maine Wire with a traditional news site, Posik said the website features a large logo on the right side of the page stating that it’s a product of the Maine Heritage Policy Center. The site also invites readers to click through for more information.

“I don’t think we’re trying to pass ourselves off as a newspaper,” he said. “I don’t think it’s intended to read like a newspaper.”

Gagnon agreed that the popularity of the site and others like it has been fueled by the growing polarization of the political parties and the instinct readers have to find information that reinforces what they already believe.

On Facebook, the Maine Wire has 5,578 followers and the Maine Heritage Policy Center has 7,434. Website traffic is largely driven by email subscribers who get updates when new stories are posted to the site, Posik said.

The Maine Beacon

The Maine Beacon was launched a little more than two years ago with a website and podcast, said Mike Tipping, communications director for the Maine People’s Alliance.

“The philosophy behind it was we wanted to put information out there that wasn’t being covered,” he said.

The site is especially interested in highlighting activism and organizing, such as a recent visit by veterans who wanted to challenge U.S. Rep. Bruce Poliquin, over his position on food-stamp spending. Poliquin, a Republican, represents Maine’s 2nd District.

“We’re proud now to be the most-shared political website in the state,” Tipping said.

To back that up, Tipping prepared a Facebook share report that covers the week of April 23, 2018. It shows Beacon stories were shared more than 9,600 times. By comparison, politics and opinion pieces in the Portland Press Herald were shared 5,128 times, the Bangor Daily News State and Capitol blog had 268 shares, Maine Public had 151, and the Maine Wire recorded 149, according to the report.

When it comes to Facebook followers, the Maine People’s Alliance has 13,839 while the Beacon, its affiliated online publication, has 953.

The Beacon’s readers are politically active, particularly those “engaged in the resistance” who were sparked to action by the 2016 election of President Donald Trump, Tipping said.

Tipping said the Beacon is fact-based and hires trained staffers, it does not seek to attack and replace traditional media, and it tries to highlight not just those in power, but “people without power.”

He said their contributors include younger voices, people of color, and people who are transgender.

Tipping cited a column written by a University of Maine student drawing attention to misogynistic banners on campus last fall that greeted female students and their parents. The student wrote a column for the Beacon that was shared 25,000 times. And because there was a link embedded in the story, the student was able to raise $6,000 to reopen a women’s center on campus.

It’s that kind of activism that’s at the heart of what the Beacon is trying to do, Tipping said.

The Beacon also links to and highlights work by The New York Times and The Washington Post.

In a letter to readers, Beacon editor Lauren McCauley said the site’s mission is to provide a platform for voices that often aren’t featured in other outlets.

“At Beacon, we are committed to rigorous, factual reporting and are transparent about our interest in promoting a progressive worldview,” she wrote.

Being an informed reader

Tipping, of the Maine People’s Alliance, argues that the mainstream media often practices “false balance” by interviewing both sides of an issue and presenting them equally even when such treatment is unwarranted.

The partisan stalemate/partisan sparring headlines used to describe the end of the legislative session made it seem as if both Democrats and Republicans were to blame, Tipping said. In his mind, there was only one group that refused to extend the legislative session – House Republicans.

The headlines used by the Press Herald and Bangor Daily News were “kind of a pox on both houses,” he said.

“I think there’s a different kind of balance,” he said. “I think we do a lot to get to the truth. There’s a different kind of bias that comes into coverage from traditional outlets.”

Todd Benoit, president of the Bangor Daily News, responded to criticism from both the Beacon and the Wire, saying these types of groups have long complained about the mainstream media.

“Advocacy groups have always said the press has not adequately covered their views, and they have produced press releases, handouts, leaflets and their own newspapers over the years to allow their thoughts to be heard,” he said in an email. “What’s different now is the ease with which these groups can create websites and share their content through social media. But that doesn’t make it journalism, and I have yet to see the general public accept the stories these sites offer.”

David Farmer, a former journalist who served as communications director and deputy chief of staff to Democratic Gov. John Baldacci, said citizens need to be informed about what they are reading and understand that advocacy sites do not follow traditional journalistic norms.

He thinks there’s a place for the Maine Wire and the Maine Beacon, what he describes as “advocacy-style reporting.”

“All of us have to challenge ourselves to get information from multiple sources,” said Farmer, managing director at the Bernstein Shur Group. “We need to read a local paper, a national paper and we need to compare notes.”

On the other side of the political aisle, Aaron Chadbourne, a former policy advisor to LePage, said the loss of influence by the mainstream media mirrors the decline in power of other traditional institutions, including the two major political parties. Sites like Beacon and the Maine Wire are just a small part of the changing media landscape, he said. Politicians and others who work in government are looking to options such as Facebook Live – which allows live streaming of news events – to get their message out unfiltered.

Chadbourne finds another trend even more concerning. “People are now selecting to avoid conversations or ideas that make them uncomfortable,” he said. “That’s the more harmful thing to worry about.”

Other agenda-based sites have been less transparent

While the Beacon and Wire label their content, other politically motivated websites have been anonymous, a trend highlighted in a recent article on Politico.

The piece suggested that more “Baby Breitbarts” — a reference to the right-wing site once run by former Donald Trump advisor Stephen Bannon — may soon be popping up all over the country. The story revolves around the Tennessee Star, a conservative site that looks like a traditional news site and, until contacted by Politico, was anonymous.

The Politico story also mentioned a similar site much closer to home — the Maine Examiner. Launched by Maine Republican Party Executive Director Jason Savage, the site published several anonymous stories in 2017 that were highly critical of Democrat Ben Chin, who was running for mayor of Lewiston.

It wasn’t until Democrats asked for a state Ethics Commission investigation into possible campaign finance violations that Savage disclosed that he was behind the site — off the clock from his duties at the party — and started labeling the content so readers would know who is producing it.

Chin lost the election by 145 votes, prompting some to speculate that Savage had tipped the close election with his anonymous website, according to a December story in the Bangor Daily News.

A pro-Trump site that continues to be anonymous here in Maine is Maine First Media, which uses the slogan “Real News for Real Mainers.” The site runs some stories with bylines and some without, with headlines like “Open-border Leftists Plot to Invade Rural Maine with Muslim Refugees” and “AFL-CIO Officer Defends Illegals Over Mainers.”

Rep. Larry Lockman, R-Amherst, who writes bylined articles for the site, did not respond to a message left on his phone or an email asking about the depth of his involvement with the site. One of his recent stories was headlined “The Swamp Queen Strikes Back: Off With Their Heads.” in which he takes on House Speaker Sara Gideon, D-Freeport, for the way she conducted House business in the waning hours of the legislative session.

In an attempt to reach the site’s owners, The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting also sent a message to the “contact us” email on the site. It came back with a reply from someone who said they might answer some questions via email, but would not grant a phone interview or address any questions related to the identity of who runs the site.

In 2010, Mainers encountered The Cutler Files website, an anonymous site that attacked independent gubernatorial candidate Eliot Cutler. It wasn’t until after the election — in which Cutler finished a surprising second to LePage — that an ethics investigation into possible campaign finance violations revealed that Democrat Dennis Bailey and Thom Rhoades, husband of Democratic primary candidate Rosa Scarcelli, were behind the site.

The Politico story reports that the men behind the Tennessee Star, Steve Gill, a conservative commentator, and Michael Patrick Leahy, who writes for Breitbart, say they want to expand into other states or regions and have registered domain names such as newenglandstar.com, theohiostar.com and thewisconsinstar.com.

News with a view

Until the mid-1940s, it was common in Maine and elsewhere for newspapers to have an expressed political party bias, said Maine State Historian Earle Shettleworth. At that time, it was one of the reasons there were multiple publications serving the same community.

“Literally right up through the mid-20th century, it was pretty commonplace for newspapers to have a declared party affiliation,” he said.

As a boy growing up in Portland in the 1950s, Shettleworth said he remembers one of the local papers serving as a party organ for the GOP. And James G. Blaine – 1884 Republican presidential candidate, U.S. House Speaker and politician whose home now serves as the Maine governor’s mansion – ran the Kennebec Journal in Augusta in service to his party.

But after World War II, competition for news from radio and television meant fewer newspapers could survive. As the once-political papers folded and merged, newspapers gradually adopted the concept of balanced coverage to serve all readers, Shettleworth said.

“There emerged a view that if we’re one paper we have to serve the entire populace, the entire community,” he said.

Staffing, consolidation concerns

As newspapers continue to compete with television, websites and social media, experts say they worry about the lack of reporting resources at mainstream outlets, consolidated ownership, and the trend of multiple newspapers running the same news story, which means fewer perspectives on the same event.

University of Maine at Orono associate journalism professor Michael Socolow, a media historian, said while it’s difficult to judge the impact of the advocacy websites because there’s little data to show their reach, he is concerned about cutbacks at the Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News.

“They have far fewer reporting resources,” he said. “That has to have an effect. There has been a growing reporting void in the state.”

Neither Benoit, of the Bangor Daily News, nor Schechtman, of the MaineToday papers, addressed criticism about staff cuts at their publications and whether cuts have affected their ability to cover local news. In October, the Bangor Daily News announced it was cutting staff by five in a bid to become “a more efficient, more effective news organization.”

Melcher, the political science professor, said his concern is about the deterioration of local news coverage – something readers can’t get from national outlets.

“That’s the bigger problem,” Melcher said. “Many more local things aren’t getting examined.”

Nationally, the Nieman Journalism Lab notes that newsroom jobs have dropped significantly, from a high of 56,900 in 1990 to 24,000 now.

Farmer said with the Press Herald, Sun Journal, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel all owned by the same company, it means only one reporter is often covering a particular news event. And since the Bangor Daily News and Maine Public, the state’s PBS affiliate, share content, the same is often true for them.

Additional pressure comes from attacks by politicians, Socolow said.

“Politicians are attacking the media at an unprecedented level,” he said. “That’s making the job of a journalist far more difficult than it used to be.”

Melcher said advocacy sites like Maine Wire and Maine Beacon may continue to put pressure on the mainstream media, but readers who visit their sites likely know they aren’t getting an objective view of events. And while some, like Dutson, worry about an erosion of democracy without a common baseline for understanding events, Melcher said he’s more worried about what’s lost when people don’t trust journalists.

“I think we’re losing something in the lack of faith in the mainstream media,” he said.