As part of her work as a 2021 Switzer fellow, Natalie Lord has launched the website, A Rising Tide?, highlighting women’s experiences as oyster producers.

The project is billed by its sponsors as the first case study to analyze gender in Maine and New Hampshire’s aquaculture industry through visual storytelling. Its goal is to share the photographic and narrative data the research participants collected on their experiences owning and operating an oyster farm in Maine and New Hampshire.

The Maine Monitor has partnered with Lord (who was advised by Dr. Catherine Ashcraft), the Robert and Patricia Switzer Foundation and the New Hampshire Sea Grant to republish the series that showcases the stories of four women oyster farmers and why it’s important to study women in aquaculture. The narrative below is written in the first person by Amanda Moeser.

Birds Eye View

Here I am (photo above) with another oyster farmer, doing some reconnaissance for her upcoming standard lease hearing. From the air, we look so small, which is odd because that’s not how I feel when I’m out there.

Of all the people I work with in the area, her and my friend Emily are the easiest to get along with and the most inspiring and relatable. They are both supportive, tenacious, and independent.

Shuck ‘Em

I laugh and am mildly disgusted when I see people invest $30,000 in a shiny new boat (photo at right) for oyster farming.

Part of it is jealousy — I think it would be nice to feel safe, have a navigational system, a hauler, a motor that starts without fail, all the bells and whistles — things that were out of my reach when I got up and going.

But the bigger part of me is immensely proud and grateful. I started my farm with a 1995 Buick Century and an 11’ skiff.

I built a beautiful farm in a prime location with very little aside from my own brains and brawn.

I have zero farm debt which makes me better able to withstand market and environmental fluctuations.

What’s best is that this model is replicable and accessible to all, not just dudes with cash to blow.

Bottom Seeding

This is my favorite way to grow shellfish — bottom seeding and hand picking. All I need for gear is a 5-gallon bucket, harvest bags, and a sled to drag across the mud. Oysters grown this way are hearty, flavorful, and top notch quality.

It frustrates me that as a woman and beginning farmer, I qualify for no-cost catastrophic crop insurance through the USDA; however, the species I want to grow (quahogs) and the methods I prefer to use (bottom-seeding) are not eligible for coverage.

In my opinion, this is a prime example of long-standing, unaddressed institutional bias at the federal level, but it also happens within state policy, university research initiatives, financing, and industry advocacy organizations. Of all the barriers that I’ve encountered, institutional bias is the most concerning and difficult to address.

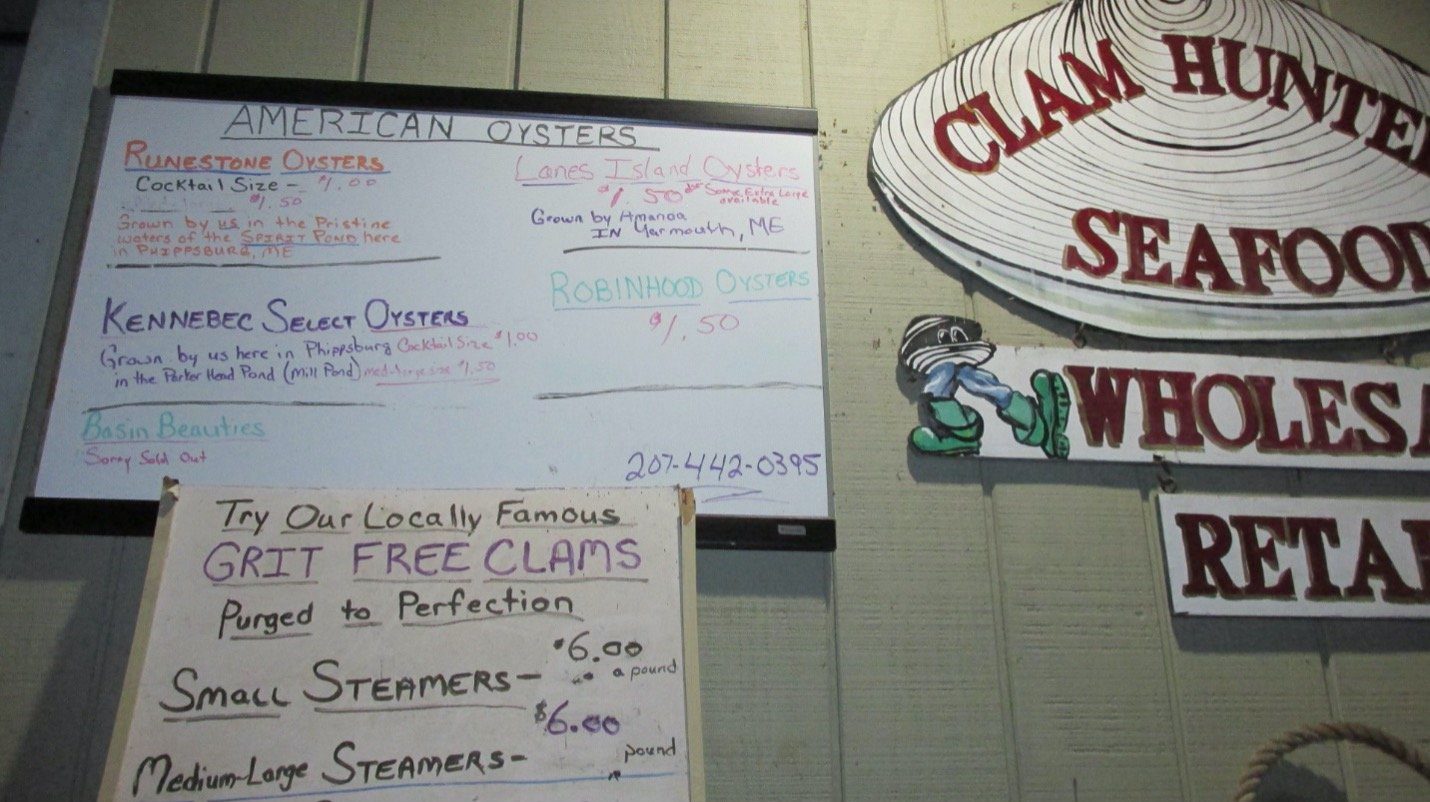

Lanes Island Oysters — ‘Grown by Amanda in Yarmouth’

Terry and Sally were my first ever customers and have been buying from me ever since. I appreciate their shop because I overwintered oysters in the cooler, it’s close to home, and they always treat me fairly.

Every time I drop off oysters, I’m there for at least an hour because we like to catch up and talk about our farms.

Sally has her own farm and a clam license, too, and does all the day-to-day stuff with customers at the shop. It takes the two of them, working full-time and more, to keep the business going.

It annoys me when the “people in charge” encourage direct-to-consumer consumer marketing as a way to sustain small-scale fishing and farming ventures. It’s another full-time job that I don’t need on top of my already full-time job, various part-time jobs, community service, and family responsibilities. I like my middle(wo)man and our businesses work in tandem.

Wharf

One of my favorite journal articles on the role of gender in fisheries is titled, “Before we ask permission, now we give notice.” That’s partly how I feel about the wharf where I work and keep my boat.

Now I am free to come and go as I please. It’s a critical access point for my farm because it doesn’t always freeze up in the winter and I have parking in the summer thanks to one of the fishermen.

I look forward to going to the dock because I love the people and the stories that I hear while I’m down there.

I strongly believe that gender norms have a foothold in our society and function in insidious ways, but I also know these guys accept me and genuinely want to see me succeed. For me personally (and gender relations more broadly), it’s important to continue working with men, as well as women.

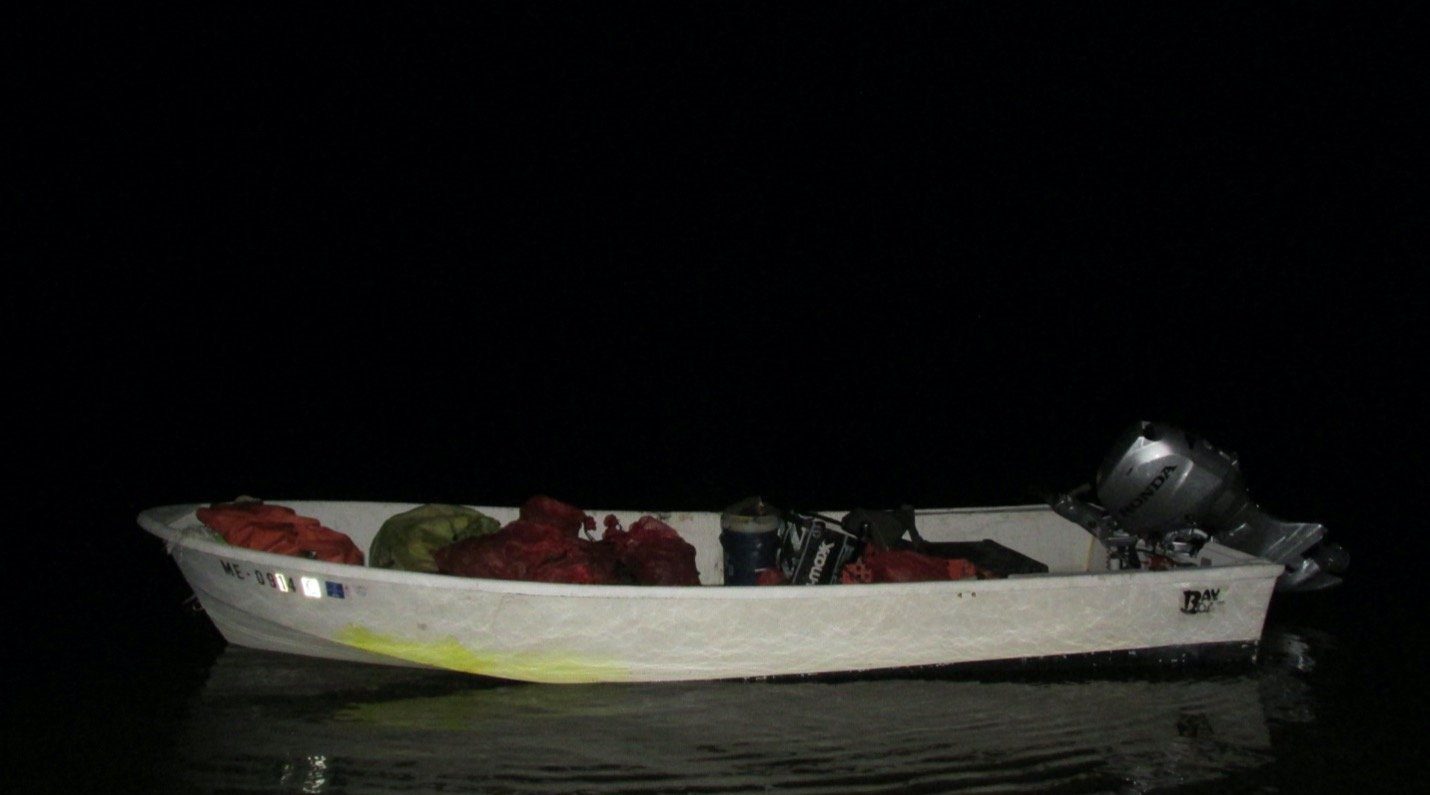

Night Tides

Most oyster farmers pack things up for the winter — but my schedule, where I work, and gear are more similar to wild clammers — so they comprise a bulk of my social network.

It took me a long time to get up the courage to take the boat out alone after dark in the winter. It’s pitch black and hovering around freezing. I don’t have the luxury of a heated cabin, lighted decks, navigational systems, depth finders, and GPS, which are all common on lobster boats and other fishing boats.

For the first couple years, one of the guys would drop me off at Lanes Island (the uninhabited island where I farm) before the tide and pick me up on their way in. Last year, one of them took the time to help me practice navigating in the dark.

Now I am confident enough to go alone, but we still check on each other and make sure everyone gets in safe at the end of the night. It’s not an understatement to say that I trust them with my life and these relationships are a matter of life and death.

Farm Sunset

This is just a pretty picture of my farm before sunset. It isn’t until the tide drains out that I can see the fruits of my labor. I like that it’s hidden away under the surface.