Thousands of Maine children are living in poverty because of a crisis that goes unnamed.

It is creating a generation of children who struggle in school, will have a hard time qualifying for a decent job and are more likely to have run-ins with the law and suffer from mental health problems.

It is costing all Mainers millions of dollars in programs to help these children and their families. At the same time, those who know the problem best are not sure those programs can ever succeed. Many think more needs to be done.

But they acknowledge the crisis doesn’t have a chance of being solved if public officials, educators, social service agencies and others won’t publicly put a name on it. The very people who are in the business of helping the poor are afraid to talk publicly about it. They don’t want to appear to be making moral judgments about those they want to help. They don’t want to shame the victim.

But dig deep enough, talk to enough experts, review enough academic studies and the name of the problem emerges: too many single parents having children they can’t afford to take care of.

A nine-month investigation by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting that included original analysis done for the Center by university sociologists, interviews with state and national experts, days and hours spent with childcare providers, educators and single mothers and fathers reveals that the inability to lower the poverty rate for families with children in Maine is due in large part to a change in the makeup of the state’s families:

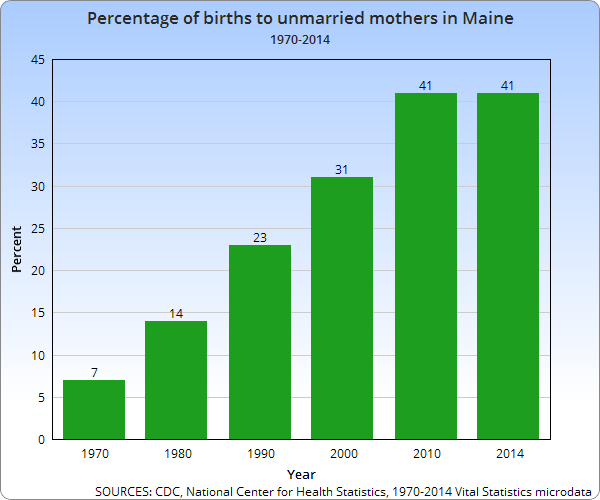

- In 1970, 7.1 percent of births in Maine were to unmarried women.

- In 2013, 41 percent of births in Maine were to unmarried women.

That’s almost a 500 percent increase in a little more than a single generation.

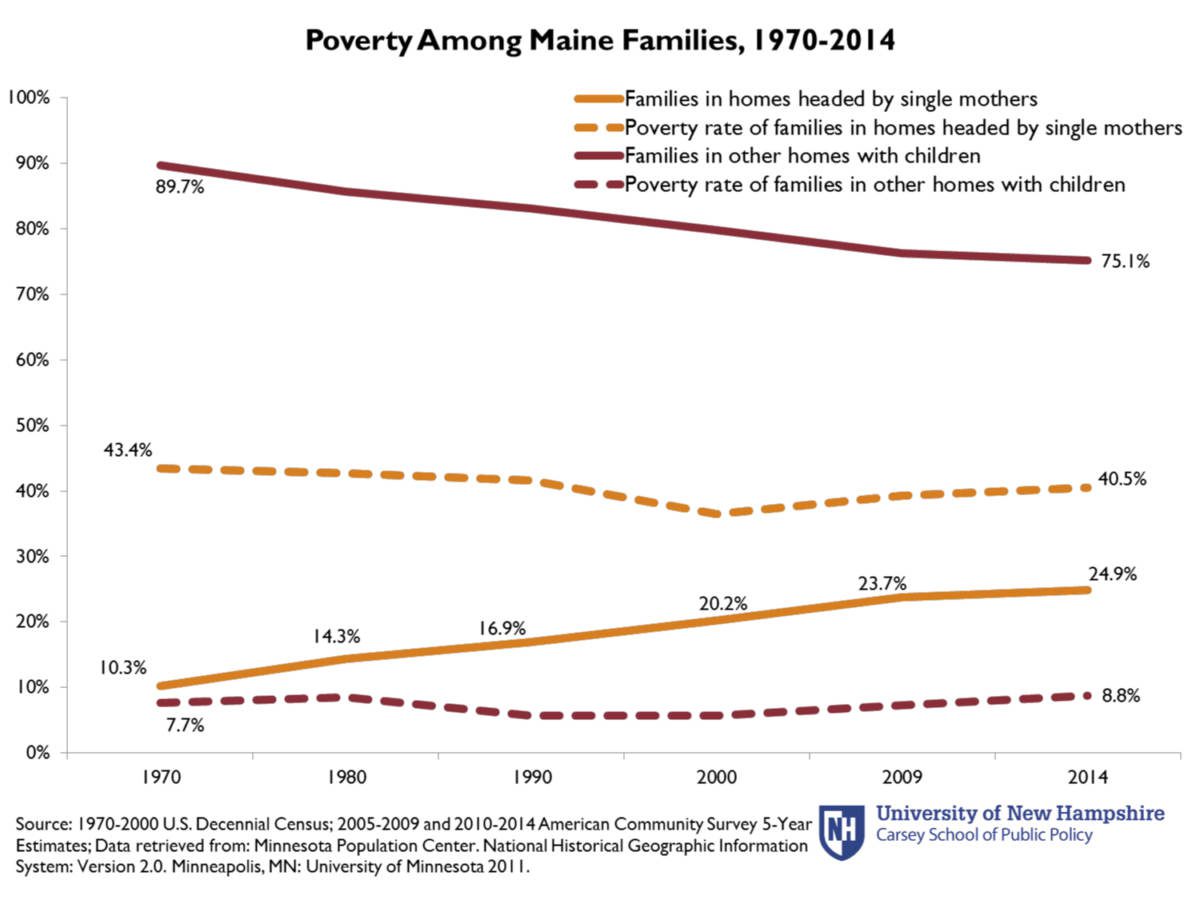

The poverty rate for Maine families in 2014 would be 27.8 percent lower if the share of families headed by single mothers remained at the 1970 level, according to researchers at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey Center for Public Policy.

As of 2014, the most recent statistics available, 111,000 of Maine’s 260,000 children, age birth to 18, are classified as living in low-income families and families living at the poverty level.

For thousands of Maine children and their parents, the word “family” doesn’t mean what it used to mean. It doesn’t mean safety or security or comfort.

Instead, it means being poor. It means being raised by a single mother who, no matter how hard she works, can’t earn enough money to feed her children.

It means families that move many times a year because there isn’t enough money for rent.

It means mothers who can’t afford to take their children to the doctor, who can’t hold a job because they don’t have money for childcare or they don’t have a car to get to the job.

What about the fathers? Most single mothers will tell you: Forget them. They say they’re off with the new girlfriend or in jail.

“I think we have in our county a transient male population that moves from home to home, family to family, mom to mom” said Renee Whitley, executive director of the Franklin County Children’s Task Force, the child abuse prevention agency based in Farmington.

And when children are raised in that kind of poverty and deprivation, their brains are literally harmed, setting the stage for a lifetime of negative effects. Columbia University neuroscience and education professor Kimberly G. Noble described in the Washington Post in 2015 how poverty hurts children:

“When parents are distracted or depressed, family life is likely to be characterized by conflict and emotional withdrawal rather than nurturing and supportive relationships with children. Parents don’t talk and read to their kids as often and make less eye contact with them. This accumulation of stress in children’s lives has cascading effects on brain systems critical to learning, remembering and reasoning.”

Claire Berkowitz, head of the advocacy group The Maine Children’s Alliance, said that those effects don’t only hurt the child — they end up in the classroom.

“They’re showing up without the cognitive abilities of the kids from a well-resourced home,” said Berkowitz. “If we want a future workforce and a contributing member of society, these are the kids we have and … they’re more expensive to educate.”

Andrew Schaefer, a research scientist at UNH’s Carsey Center, said that not all children raised by single mothers meet such a fate. And there can be advantages in being a single mother, too.

“I would be cautious about implying that the rise in single-parent families is completely negative because it increases poverty rates,” said Schaefer. “Economic and social changes that took off in the 1970s allowed for many women to end marriages who otherwise couldn’t control their economic future, their fertility, or it was socially unacceptable to leave. For these women (and many of the women who conceive out of wedlock today), being single can have many benefits (including benefits for children) and can be empowering, even though they are far more likely to be in poverty.”

Sen. King: ‘looming crisis’

U.S. Sen. Angus King, the political independent who served two terms as Maine’s governor, said the state faces “a looming crisis” because the thousands of children being raised in poverty — including the children of single parents — won’t have the education, health or skills to be the next generation of productive citizens.

“We’re already short of workers, already suffering from a negative demographic situation — to waste potential workers is going to cripple our economy.”

“It’s about compassion,” he said “but it’s also about economic self interest.”

And there’s one more risk to children in families headed by unmarried parents: child abuse and neglect. Based on state reports, the single largest percentage of cases of abuse and neglect investigated by the state in 2015 came from homes headed either by single mothers or by two unmarried, cohabiting parents, at 35 percent each.

Susie Maxwell, the pastor at Centre Street Congregational Church in Machias whose ministry includes working with many poor families headed by single mothers, said that avoiding a public discussion about the issue has been doing a disservice to the needs of the single mothers and their children.

“You have to be able to name it or you can’t work with it,” she said. “You have to have balls — it’s critical to name it.”

Some single mothers do feel shamed.

Joanne R. is in her late 30s and living in a rented house in rural central Maine with her three-year-old daughter. (The Center is not using her real name because she was the victim of domestic violence and fears for her safety.)

She rejects the idea that there’s something intrinsically irresponsible about being a single mother.

“I think that there is a lot of blame placed on single moms, judgment that, you know, oh, (they) just keep popping out kids and should get a job,” said Joanne R.

And in a politically charged era when the LePage administration has spent six years targeting “welfare fraud,” allies of the poor don’t want to give any ammunition to politicians they believe unfairly denigrate the poor. They say that being a single mother in Maine doesn’t mean you’re a bad parent or bad person.

Many single mothers in Maine manage to provide their children with the love, care and opportunities they need and deserve. In interviews across the state, from kitchens to schools to social service agencies to police departments, the chorus was universal: single mothers want the best for their children.

But there’s a catch: Wanting the best and being able to provide the best are two different things in the lives of most of Maine’s single mothers.

The economic reality is that in a single-parent family, there’s only one income, and it’s usually low and insufficient. The Children’s Defense Fund, a national group advocating for better programs for children, said in 2014 that “more than two full-time minimum wage jobs were necessary to be able to afford a fair market rent two-bedroom apartment in Maine and still have enough left over for food, utilities and other necessities.”

The emotional reality is that a single parent’s psychological reserves and resilience often aren’t enough to handle the demands of work and one, two or three children whose father or fathers provide little-to-no help or support.

And the practical reality is that getting public assistance of any sort usually requires multiple frustrating interactions with multiple government agencies, which means things — and people — can get lost between the cracks.

Skowhegan resident Adena Wilcox is a single parent with one son, Michael. She said she’s needed the help of food pantries and soup kitchens in central Maine over the last three years in part because her modest income from a job at Walmart disqualified her for the food stamps she had been getting when she was unemployed.

Wilcox said she then lost her job, tried to get reinstated to the food stamp program and was denied because of her failure to verify information the state had requested. She then tried to get a food voucher at her town office; officials there said the town no longer gives out food vouchers.

Wilcox ran into even more roadblocks to getting back on food stamps. Sitting with Michael at St. Anthony’s Kitchen in Skowhegan, where they’d just gotten dinner, Wilcox said she was frustrated with the endless amount of red tape, rules and requirements.

“This is a vicious cycle,” Wilcox said. “To get food stamps you are required to do volunteer work while looking for a job and taking care of children by yourself.”

“How is this possible to volunteer, find a job and take care of Michael without any help?” Wilcox said.

A ‘perpetual crisis’

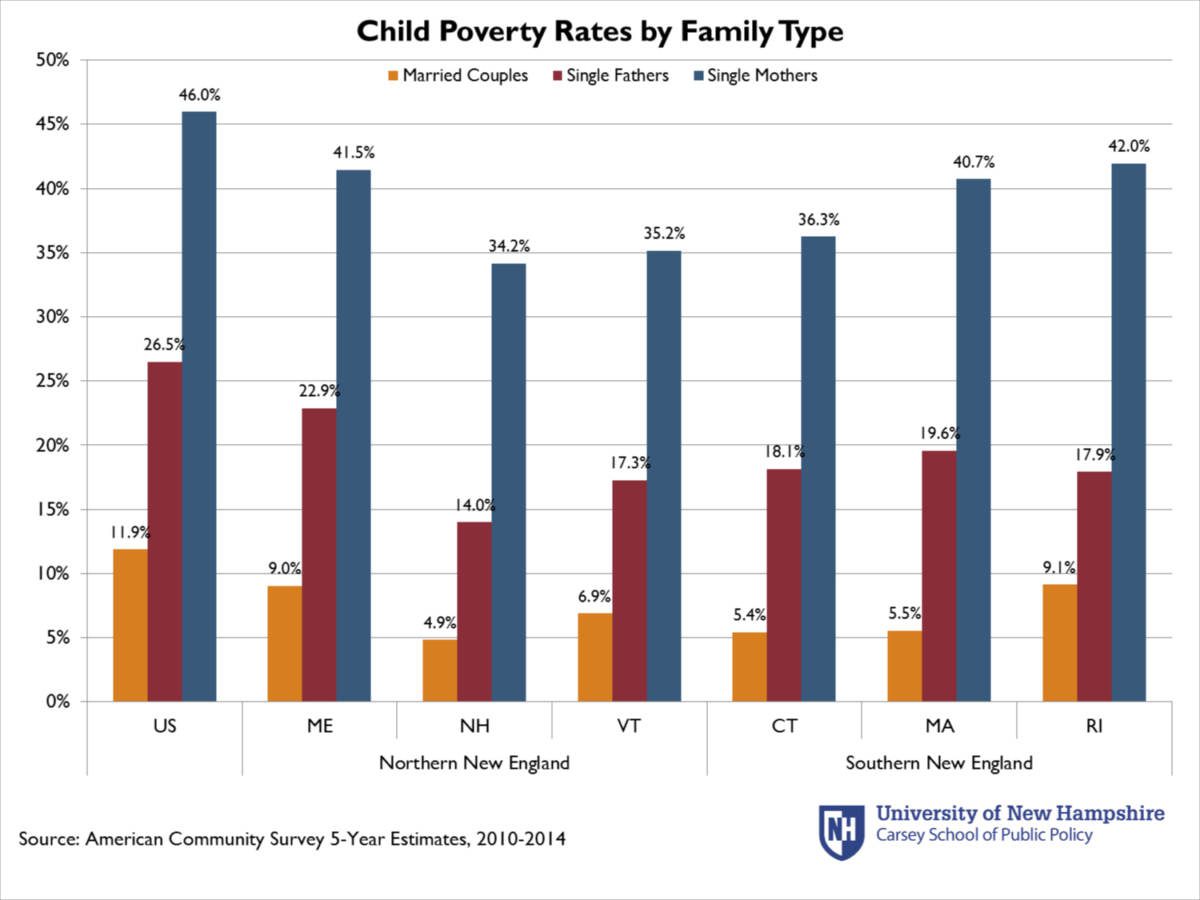

Of the tens of thousands of Maine children living in poverty or just above it, most are living with just one parent, usually a mother. In 2014, 69 percent of Maine’s children in poor families and 54 percent of children in low-income families were being raised by a single parent. In middle- and upper-class families, only 19 percent of the children were being raised by a single parent. The poverty level for a four-member family (two parents, two children) in the U.S. is set at an annual income of $24,300; low-income is defined as $48,600.

Well-educated people get married and have children; those without college degrees are much more likely to have children outside of marriage. “The proportion of first births that occur outside of marriage is only 12 percent for those who are college graduates; it’s 58 percent for everyone else,” writes Brookings Institution economist Isabel Sawhill, who has written extensively about single-parent families.

For the majority of Maine’s single mothers, the American dream — that hard work will pay off in a better life for you and your children — isn’t happening. Their lives consist of endless emergencies, low-paid jobs and grinding, dead-end poverty that promise to be the inheritance and future for their children.

“Families living under poverty live in perpetual crisis … for single parents, the instability is even greater,” said a report written in late 2015 by consultants for the city of Auburn. “Two out of three fell behind on utility bills. 60% experienced a car breakdown with no money to fix it. Almost a third had to move due to inability to meet housing expenses.”

The researchers at Child Trends, a national research nonprofit that provides data to policymakers , synthesized years of demographic data and a raft of academic studies in a December 2015 report that concluded, “Children born to unmarried mothers are more likely to …experience instable living arrangements, live in poverty, and have socio-emotional problems.

“They are more likely to have low educational attainment,” the report continues, “engage in sex at a younger age, and have a birth outside of marriage. As young adults, children born outside of marriage are more likely to be idle (neither in school nor employed), have lower occupational status and income, and have more troubled marriages and more divorces than those born to married parents.”

So why do single women have children without the support of a father?

Poor women have the same desires as other women, said Donna Beegle, the author of two books on poverty and families, who holds a doctorate in education and consults with several communities in Maine who are trying to fight poverty.

“Women in poverty, like all humans, love children,” said Beegle, who grew up in a migrant labor family.

“On a personal level, I had six pregnancies living in the crisis of poverty,” she said. “Only two of them survived that war zone. I was going to love them, we would play, we would have fun and figure out a way to get by and maybe they would be smarter than me and make it.

“That was my world view.”

Ellen Farnsworth, whose job is to visit families in Washington County and advise parents on how to raise healthy children, said the young women she sees often lack self-confidence. They then seek confirmation of their worth in relationships with unsuitable men and the unconditional love of a baby.

“I so often see young women, it’s so important for them to be in a relationship that it doesn’t matter with whom, so long as they’re in a relationship. That might last two weeks and then they’re on to another one … they could have a child or two, and the child is calling each one of these men ‘Daddy,’” said Farnsworth.

And once the babies arrive, the rosy glow of romance and anticipation turn into something starkly different.

“I didn’t know how hard it would be,” said Joanne R., the single mother.

“I had nothing to compare it to, I’d never been a single mom before, I thought I’m capable of a lot of things, so why not?

“But it’s been — I don’t even know how to put it in words — it’s been a complete roller coaster. Happy, sad, happy, sad, happy, sad, stressed out, angry. And all I want to do is make her happy.

“I think the one thing that would make her the happiest is to spend time with me, but I don’t have any.” Joanne R.’s voice breaks. “I don’t have any extra time.”

What’s happening with mothers like Joanne R. in Maine is a reflection of a dramatic, decades-long shift in marriage and childbearing across the nation, brought on, experts say, by changing social mores and the loss of well-paid manufacturing jobs that didn’t require more than a high school education.

“I get the idea if you don’t have much hope in your life, don’t see a positive trajectory and think you’re going to be poor forever, what’s the point in deferring childbearing. What’s the point in marrying a guy who has very poor economic prospects himself,” said Brookings economist Sawhill.

But what’s emerged from that shift is a chaotic new form of the family. So-called “baby daddies,” often unemployed, live for a while with a woman, get her pregnant, — and then go off and live with another woman and her kids, only to repeat the cycle and move on once more, according to a 2014 report in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science and confirmed by Maine’s Office of the Attorney General.

“Mothers have multiple children with fathers; the fathers have multiple children with mothers; the mother had four children with four different fathers and each one of the fathers also had another child with another mother,” said Debby Willis, describing families that she’s dealt with as chief of the state attorney general’s child support division.

The 41 percent of births in Maine to unmarried women is close to the national figure of 40.2. But the national number reflects much more racial diversity than the number for Maine, which is 95 percent white. According to the CDC, the percentage of births to unmarried Maine women is 15 percent higher than the national percentage of births to unmarried white women, which is 35.7 percent.

According to the U.S. Census, Maine is among the top three states in the nation for the percentage of white families headed by single parents in 2014 — Vermont and West Virginia are the top two at 35 percent, while Maine is barely behind at 34 percent.

Another statistic that reveals the trend toward single-motherhood is the simple fact that, in the past, the vast majority of babies in Maine were born to married parents. In 1990, for example, of the 17,300 infants born, 78 percent were born to married women; 22 percent to unmarried women. Twenty-three years later, percentages were well in the other direction: 41 percent of kids were born to single mothers.

Other factors

There are several contributing reasons beyond single-parenthood for the number of Maine children who live in poverty:

The LePage administration’s welfare changes in 2012 limited families to receiving a total of five years of assistance from the federal-state program called TANF. The changes cut at least 1,500 needy families off the program. Those families, according to University of Maine social work professor Sandra Butler, included “an estimated 2,700 children.” More families are cut off each subsequent year when they reach the five-year limit.

The state’s supply of well-paying jobs that sustained families has dwindled with the shuttering of shoe, lumber and paper mills.

The 2007-09 recession hit job and wage growth in Maine hard, and “average weekly earnings for Mainers today (are) lower, in real terms, than they were in 2007,” according to the Maine Center for Economic Policy.

But much of the state’s poverty, especially child poverty, results from the growth in single parenthood, according to those who have studied the problem.

“If you look at the data, it takes you five minutes to realize that single moms are a significant portion of what drives disadvantage in communities in the state of Maine,” says Tony Cipollone, head of one of the state’s largest philanthropies, the John T. Gorman Foundation.

“If you look proportionately to the degree that that population affects the overall poverty rate in Maine, it’s substantial.”

The shift away from having children while married echoes Brookings Institution researcher Ron Haskins, “has increased the nation’s poverty rate, increased income inequality.

“We have,” he said, “dug a very deep hole.”

In one of the most in-depth series that the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting has ever published, Senior Reporter Naomi Schalit discovers and calls attention to a dramatic change in the Maine family — a 500 percent increase in the proportion of children born to single parents in the last 43 years. Nearly half of all births in the state are now to mothers who are not married.

Because most of those single parents can’t afford to raise a child — or two or three children — they are destined to live in poverty. And when children are raised in that kind of poverty and deprivation, their brains are literally harmed, setting the stage for a lifetime of negative effects, according to the experts interviewed by Schalit.

At a time when poverty and welfare have become polarizing political issues in Maine, the very people who know the most about this problem don’t want to talk frankly about it for fear of backlash against the parents and children they are trying to help. It took nine months of digging into the problem — interviews with national experts, days spent with single mothers, time in the state prison with single fathers and repeated visits with teachers, social workers and public officials — for Schalit to bring forward this essential story.

David Leaming contributed reporting to this story. Reporting for this story was supported by grants from the Samuel L. Cohen, Hudson and Maine Health Access foundations. Demographic analysis was provided by Andrew Schaefer, Vulnerable Families Research Scientist, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

This is the first in a series of five stories on this subject. To read more about what went into the reporting of this story, click here.