This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

This is part of a continuing series.

When Corey Hebert’s attorney came to see him at the Aroostook County Jail, they sat face to face. Yet the two men knew they had little privacy to speak freely, said Hebert, who was jailed in 2019 for allegedly trafficking drugs.

His court-appointed attorney, John Tebbetts, advised him to speak softly so their conversation wouldn’t be heard by the guards posted nearby.

“But when we talked over the phone we were more free because these calls — we were told — were not supposed to be recorded,” Hebert said. “And here we are finding out that they are.”

On those calls, Hebert remembers talking with his attorney about plea offers from the district attorney’s office to settle his case and strategies to get a better deal. His drug trafficking charge would eventually be dismissed.

Now, Hebert said he’s left feeling betrayed and with a “lump in the stomach” after learning that law enforcement personnel in Aroostook County elected to “playback” — or listen to — recordings of more than a dozen phone calls between him and Tebbetts before he was released from jail.

Between June 2019 and May 2020, the Aroostook County Jail recorded 622 calls that defendants made to 20 attorneys, including Tebbetts, according to records obtained by The Maine Monitor. It is the largest mass recording of attorney-client phone calls in a Maine jail disclosed to date.

RELATED: Jailed defendants expected private attorney calls. They didn’t always get them.

Jailers can legally record and listen to phone calls of people in their custody — and frequently do — but are explicitly barred by state law from interfering with attorney calls. Those attorney-client calls are supposed to be declared private and out of the reach of law enforcement investigators. Federal courts have said that defendants have a constitutionally protected right to seek confidential legal advice to develop a defense for trial.

Aroostook County is an example of the worst that can happen when jails record phone calls to attorneys, a Maine Monitor investigation found, and the calls to attorney Tebbetts particularly stand out. Aroostook recorded 304 calls to Tebbetts’ law office from 49 jailed clients in a year, more than any other attorney in the county, records show. Forty calls were from Hebert.

In Aroostook County, a wide range of law enforcement officials routinely had access to recordings of Tebbetts’ client calls without his knowledge or consent, according to data from the sheriff’s office.

The data show that sometimes law enforcement personnel elected to “playback” those recordings. That term – playback – is crucial to understanding the recording system. It means “the call was listened to by the user with the name beside it,” according to Aroostook County Sheriff Shawn Gillen.

Securus Technologies installed the phone system in Aroostook and 13 other Maine county jails. Joshua Martin, the then general counsel for the company, provided a similar definition of the term “playback,’’ while testifying in 2018 as part of a federal lawsuit in Kansas.

“Playback, which is just that, someone listening to the call,” said Martin.

The same term “playback” appears in records Aroostook County provided to Tebbetts and that The Maine Monitor reviewed. Usernames of jail administrators, county employees and even a U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent assigned to the Maine drug enforcement task force appear repeatedly with the “playback” of 58 recordings and the “download” of 17 more recordings of calls jailed defendants made to Tebbetts, according to records Tebbetts received from the sheriff’s office in August 2020.

“I was not notified by any of these people that they had listened to my phone calls or downloaded my phone calls,” Tebbetts said.

The data does not detail why any of the users apparently selected the “playback” option or how long they listened to the recording. The county denied multiple requests by The Maine Monitor to interview county employees who used the system.

Data show that the same individual users repeatedly selected “playback’’ on calls to Tebbetts’ phone number. Calls with the same jailed client on different days were sometimes listened to by the same user. Each time, Tebbetts wasn’t told.

“God help us if they were intentionally trying to listen to my phone calls,” Tebbetts said.

The details involving Tebbetts’ calls are the latest revelations in a months-long investigation by The Maine Monitor, which previously reported that Aroostook, Androscoggin, Franklin and Kennebec county jails recorded nearly 1,000 calls jailed defendants made to their attorneys between June 2019 and May 2020. Phone calls between Tebbetts and his clients are among those recordings.

The “playback” and “download” of calls to Tebbetts reveal another layer of problems with how Maine county jails have operated their inmate phone systems.

Securus, the Texas-based company that provides prison telecom services to nearly all of Maine’s county jails, previously settled lawsuits without admitting fault in California, Texas and Missouri. The suits were brought by lawyers alleging the company unlawfully recorded conversations with their jailed clients.

In Maine, authorities have been put on notice that attorney-client calls were being recorded and, in some jurisdictions, investigators were ordered to stop directly accessing recordings through the jails.

For example, The Maine Monitor learned that three agents assigned to a statewide drug task force in Aroostook County identified recordings of attorneys during their investigations. One agent was reportedly told by his superiors “to stop listening and delete the recorded call” if he believed it was with an attorney, an email from August 2020 shows. A month later, agents statewide were ordered to get out of the jails’ phone systems completely.

Aroostook County explained that recordings were made because Tebbetts and his clients didn’t provide the jail his phone number to put on a “do not record” list. Tebbetts said he believes he provided his law firm’s phone number to members of the sheriff’s office when he opened his rural law practice in 2018, but he has no record of it. It’s the same phone number that was recorded and listened to by the jail, data show.

He disagrees with the sheriff that it was his or his clients’ fault that the jail recorded hundreds of confidential calls and law enforcement personnel listened to dozens of those recordings. Tebbetts said there was no clear process to exempt his phone number from being recorded, and he didn’t receive a letter from the sheriff after his clients’ calls were listened to with instructions on how to make it stop.

Securus added hundreds of defense attorneys’ phone numbers in May 2020 and again in May 2022 to Maine jails’ phone systems to block new recordings in response to concerns from state officials.

In Tebbetts’ cases, the defendants on the calls with him were being prosecuted by the local district attorney or state attorney general’s office. State and local prosecutors insist they do not have a practice of listening to attorney calls.

District Attorney Todd Collins, in a statement late last year, said his office in Aroostook County “has not knowingly used privileged communications between a defendant and his / her attorney in a prosecution.”

If his office “were to come into possession of privileged communications,” the court has a process to review it, he said. Collins did not respond to a later request for comment.

How the system works

Many U.S. jails record all calls, and non-attorney calls are routinely listened to by law enforcement in criminal investigations.

Fourteen of the 15 Maine county jails contract with Securus Technologies of Carrollton, Texas, for inmate phone services. Once a call is recorded, it lives on Securus’ online call platform. There, law enforcement can save, burn CDs, download and playback recordings.

Securus has not responded to multiple questions from The Maine Monitor about how its system operates. The Maine Monitor instead reviewed dozens of phone contracts, bid documents, court records, online videos and privacy policies, and spoke with lawyers and police to understand the call platform.

To protect their calls, attorneys are supposed to request that their phone number be made “private” so they aren’t also recorded by the jails’ phone systems.

The contract signed by the Aroostook County Jail with Securus Technologies says that for attorney and clergy calls, the jail has the “sole discretion, authority and responsibility for designating numbers as private.” The company can make phone numbers private, but only when instructed to by the jail.

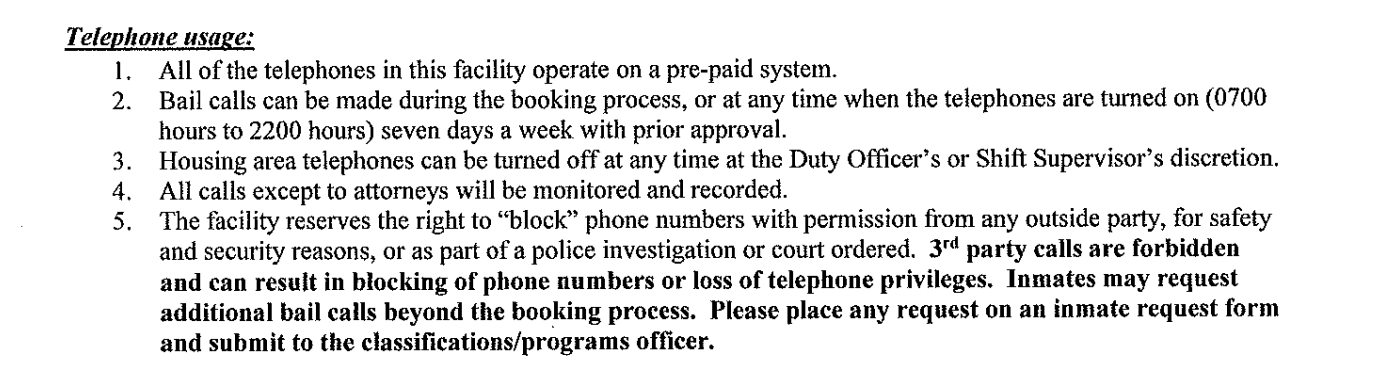

Tebbetts and his jailed clients had good reason to believe their calls were private. The handbook given to every inmate at the jail said, “All calls except to attorneys will be monitored and recorded.”

That turned out not to be accurate.

Search the database of attorney calls recorded at the Aroostook County Jail and three other jails

Aroostook County Sheriff Gillen “learned of the possibility that inmate phone calls with attorneys were being recorded” for the first time on May 7, 2020 in an email from a county insurance provider, according to a written statement. The next day he instructed the jail administrator to remove all but three employees from accessing recordings. Gillen said he told them to also survey booking information and block recordings of any attorney phone numbers not already in the jail’s phone system.

Securus Technologies within a week put all known attorney phone numbers from Maine on a list not to be recorded, and the company added to the Aroostook County Jail’s booking process a way for inmates to provide their attorneys’ name and phone number, at the county’s request, Gillen wrote.

Aroostook County officials insisted they hadn’t intentionally recorded or monitored any attorney calls at the jail. Gillen said since May 2020, the jail has blocked access to calls with attorneys whose phone numbers jail officials could identify.

“The bottom line is that no one at Aroostook has ever intentionally monitored, listened to or recorded any call that they knew to be privileged. The only time that attorney-inmate calls were recorded or monitored was when the attorney failed to provide his or her telephone number to the jail so that it could be notated by the company providing inmate telephone services as ‘do not record’,” county attorney Peter Marchesi wrote on May 17, 2022.

A regular jail visitor

As a Presque Isle-based attorney, Tebbetts is a regular at the Aroostook County Jail in downtown Houlton. A short drive off I-95, where miles of pine trees give way to farm fields, Houlton is a burst of activity along the border of the Canadian province of New Brunswick.

The jail — established in 1889 — attaches to the back of the district courthouse and overlooks the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Office, Houlton United Methodist Church and a park where people gather in warm weather to eat at picnic tables during the early afternoon.

The drive between Tebbetts’ law office and the jail in Houlton takes under an hour. He’s there so often that guards wave him into the building, where he usually spends several hours visiting with clients.

When clients in jail call his law office it is often his receptionist, Tabitha Haines, who picks up. The caller ID shows it’s a call from Securus and they’ve learned to recognize the extension for each county jail, he said.

“Tebbetts Law Office,” is typically how she starts a conversation when a new person calls.

Earlier this year, The Maine Monitor published the first articles in a continuing investigation showing how six Maine county jails recorded attorney calls and shared some of those calls with police and prosecutors. Recordings of these conversations continued to be downloaded and played by investigators through August 2021, records obtained by The Maine Monitor reveal.

Tebbetts filed a federal lawsuit in August 2020 accusing Securus Technologies of allegedly “wiretapping” attorneys and their jailed clients. Lawyers hired to represent the company vehemently denied the claim and argued that even if the calls were recorded, there was no guarantee that the conversations were privileged and therefore protected.

In the same year the lawsuit was filed, Aroostook County Sheriff Gillen revoked access to the jail’s recordings to all but a few employees — among them Support Sergeant Shanna Morrison. Gillen put Morrison in charge of reviewing and fulfilling future requests for recordings of inmates’ jail calls, he said in an interview.

Records submitted in the lawsuit list Morrison as playing back — or, as Gillen describes, listening — to one defendant’s call to Tebbetts in October 2019.

Morrison directed questions about her work to Jail Administrator Craig Clossey, who declined to comment. Data show that Clossey also played back three calls another jailed client made to Tebbetts in December 2019. Neither Morrison nor Clossey was named as a defendant in the lawsuit.

At the time, Gillen said limiting access was enough of a fix. “It just cleans it up so it’s not willy-nilly,” he said in an interview with the Monitor in October 2020. After repeated requests for an in-person interview, Gillen responded to some of the news organization’s questions with a five-page letter on June 9 of this year.

“There may very well have been calls that were monitored, listened to, or recorded, but it was never done intentionally with the knowledge that the calls were privileged,” Gillen wrote.

“Here is the bottom line. Neither I nor anyone at the County has any interest in knowing what criminal defendants are talking about with their lawyers,” he added.

Whether Aroostook County employees intended to listen to these calls or not, it has likely stymied communication between many lawyers and jailed clients in Maine, said Zach Heiden, the chief counsel of the ACLU of Maine.

“It doesn’t matter whether somebody is listening in on these conversations accidentally or on purpose. It’s going to have that same chilling effect,” Heiden said. “We want people to be able to communicate robustly and freely with their lawyers so that their lawyers can provide meaningful advice and advocacy. Without that confidential communication, there can’t be a lawyer-client relationship and the Constitution requires the state to make sure that there is that relationship.”

Gillen’s efforts to limit who could access the jail’s recordings in 2020 came too late for Hebert. County records show between October 2019 and March 2020, before the sheriff restricted access to the jail’s recordings, more county employees repeatedly listened to recordings of calls Hebert made to his attorney.

Jailed on drug charges

Hebert’s world was spiraling out of control in September 2019 when his second wife called police to their home. After his multiple-year first marriage fell apart, he began drinking and using cocaine before turning to methamphetamines, he said.

When a new woman came into his life, he got sober and baptized into the church again, he said. But their marital bliss rapidly ended. He was soon back on drugs and his new wife told Maine State Police that he was dealing, court records show.

“I was an addict and they were trying to pin me, deem me as a drug dealer and a drug trafficker,” Hebert said.

When Hebert arrived at the Aroostook County Jail that September, he signed a paper acknowledging his phone calls would be recorded and monitored, he said. The one exception was supposed to be calls with his attorney, according to the inmate handbook he was given. The instructions were clear, “All calls except to attorneys will be monitored and recorded.”

Hebert called Tebbetts dozens of times from his cell block, records show. He was unaware that their calls were being recorded.

One county employee listened to 10 recordings of Tebbetts and Hebert’s calls between Feb. 4 and March 16, 2020, including on days leading up to Hebert’s release on bail. The same employee also listened to 26 calls from other defendants to Tebbetts, data show.

In August 2020, a judge ruled state police conducted an illegal search of Hebert’s truck and the district attorney’s office dismissed drug trafficking charges that had been filed against him. Around the same time, Tebbetts learned about the trove of his phone calls with clients that were recorded by the jail. Because the charges were dropped against Hebert, they didn’t challenge the charges based on the recordings.

“It was my ‘Break Glass in Case of Emergency’ card and I didn’t have to use it,” Tebbetts said.

For a year, Hebert was held on house arrest. In the final months of probation in late 2021, Hebert had put his life back on track. He has started a successful trucking business and is sober.

Frustrated and confused

Another prisoner at the Aroostook County Jail, Harley Simon, had violated his probation from a manslaughter conviction stemming from a 2005 accident when he drove off the road, killing the front-seat passenger in his car. While Simon was awaiting a potential trial on new charges in the spring of 2020 and weighing whether to accept a plea deal from the district attorney’s office, jail records show, a county employee listened to two of Simon’s calls with his attorney, Tebbetts.

Simon served part of a 3½-year sentence at the Bolduc Correctional Facility, a minimum security state prison in Warren, Maine. He is now on probation.

During a visit from a Maine Monitor reporter at the prison, Simon said he was frustrated and confused by the news that some of his conversations with Tebbetts may have been heard by someone other than his attorney.

“There were personal things that I talked about with John (Tebbetts) and I didn’t even like to share with a lot of people,” Simon said. “They were conversations, for sure, that I had to explain to him what hell I’ve been through in the last 16 years.”

Simon has been in and out of jail for probation violations that include changing addresses without permission, driving without a license and using drugs that he was addicted to.

Simon blames his family for his repeat violations and substance use. He also said he blames the jails for not getting him medical treatment he needed for his addictions.

In an interview at the prison in 2021, Simon clutched a piece of paper with an excerpt of the call data that the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Office had given Tebbetts and that The Maine Monitor had compiled from the information. It listed the times and dates of calls with his attorney that a county employee had listened to, data show.

He became obviously upset when he read the details. He remembers the calls vividly. He and Tebbetts discussed new charges and the possible prison time he was facing, he said. The calls were professional and about his case, Simon said.

Monitoring calls between inmates and their friends and family are not uncommon. Law enforcement listen to the recordings for details that the inmates may tell friends and family that could help them prosecute the case. Officials say they also need to monitor for contraband or threats to witnesses.

“All non-privileged inmate calls are recorded, may be monitored, may be played back, and may be used for law enforcement purposes. All inmates are aware of this,” Gillen wrote.

However, calls to attorneys are off-limits for recording. Jail staff have no way to know if a call is between an attorney and client if the phone number isn’t registered as “private,” according to Gillen.

Yet, 58 calls that jailed clients made to Tebbetts were played back – or listened to – according to data turned over by the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Office. Law enforcement personnel didn’t contact Tebbetts about those recordings.

It is “troubling” that the employees apparently did not report the attorney call recordings to their supervisors or the defense lawyers, said Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU National Prison Project, which focuses on prisoners’ constitutional rights. “It shows a shocking lack of training.”

A known problem

Drug law enforcement personnel working in Aroostook County also found recordings of attorney-client calls in some cases they were investigating, according to records and interviews.

The Maine Drug Enforcement Agency agreed to a request by The Maine Monitor last year to survey agents and ask them if they were aware of “privileged jail calls’’ being found in any investigations or related criminal prosecutions. The survey revealed that agents were indeed aware of some recorded calls between attorneys and their jailed clients.

In any instance where it became evident that an inmate was talking with their attorney, the agent stopped listening to the recording immediately”

— Roy McKinney, director of the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency

Three state drug enforcement agents assigned to Aroostook County told supervisors they knew attorney-client calls were identified in investigations or criminal prosecutions, Assistant Attorney General John Risler, who coordinates drug enforcement, told The Maine Monitor.

The agents who said they knew of those privileged calls were Special Agent Forrest Dudley, Supervisory Special Agent Peter Johnson and U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent John Gaddis, Risler wrote in an email.

Ten calls to Tebbetts from his jailed clients in 2019 and 2020 at the Aroostook County Jail were downloaded by the username “jgaddis” and an additional call from 2019 was downloaded by a “fdudley,” county data show.

When calls between Tebbetts and clients at the Aroostook County Jail were downloaded, “the call was downloaded and either saved to a disc or a computer,” according to Gillen.

When asked to confirm the names of those who downloaded the calls, Gillen said in an email to The Maine Monitor in November that, “It would be safe to say they (Gaddis and Dudley) had access for drug investigations, considering they worked for MDEA (Maine Drug Enforcement Agency) at the time.” Other officials wouldn’t confirm the names of the agents who had access to Tebbetts’ calls.

The jail has deleted all information about the users and it cannot be recovered, Gillen told The Maine Monitor.

Tebbetts said he wasn’t told who had downloaded his clients’ calls before the records were deleted.

When Tebbetts asked county officials what had happened to the recordings of him and his clients, Sheriff Gillen wrote in an August 2020 email, “I spoke to Agent Gaddis and he stated that when he requested phone calls from a specific inmate, he was told if you come across a phone call between an inmate (and) their attorney to stop listening and delete the recorded call. He stated that’s what he did.”

Roy McKinney, the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency director, blamed the jails’ telephone providers for recording attorneys and sending those calls to agents during investigations. He said the agents did nothing wrong.

“In any instance where it became evident that an inmate was talking with their attorney, the agent stopped listening to the recording immediately,” McKinney wrote in a statement to The Maine Monitor. An investigation done with help from a prosecutor’s office determined none of the agents had “operated outside of their ethical duties.”

Still, the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency had enough concern to make sweeping changes in September 2020 shortly after Tebbetts filed his lawsuit. All drug enforcement agents statewide were told to immediately stop accessing any of the county jail phone systems. All requests for jail calls must now be made in writing and sent through state email, according to an agency-wide memo. If an agent discovers an attorney call, they must report it to a supervisor and commander, as well as the jail and case prosecutor.

Tebbetts said he has no reason to believe the Aroostook County Jail continues to record his phone calls. Aroostook County has yet to respond to The Maine Monitor’s request for additional data for 2020 and 2021.

“To my knowledge, and this has been verified by Securus, no phone calls between inmates and their attorneys have been recorded, downloaded, or played back since May 7, 2020” in Aroostook County, Gillen wrote.

Looking for answers

Tebbetts tried immediately in the summer of 2020 to get answers about what happened to his phone calls. Two other defense attorneys and two clients joined him in filing a class action lawsuit against Securus Technologies.

The complaint was dismissed in November 2021 by Chief Judge Jon Levy of the U.S. District Court District of Maine. Levy ruled that the lawyers hadn’t shown that the company intentionally singled out the Maine lawyers’ calls to record.

The case was dismissed without prejudice, meaning the attorneys can refile the complaint if they obtain more specific information about their recorded calls.

“It is certainly fair to think that Securus possesses some information (or, alternatively, a meaningful absence of information) that might assist the Plaintiffs in assessing whether Securus knew that it was systemically recording attorney-client calls,” Levy wrote.

Without the lawsuit, Tebbetts said he sees no way now to find out what law enforcement may have gleaned from his calls.

“This job is hard enough to do as it is, and to have that level of privacy that is necessary, be shattered — it’s continuing to play a role in my cases where it’s slowing down resolutions of cases,” Tebbetts said. “It’s just a nightmare. Some of my clients are refusing to talk on the phone with me even today.”

Initial funding for this project was provided by The Pulitzer Center. The project is also supported by Report for America and Investigative Editing Corps.

Samantha Hogan is the government accountability reporter for The Maine Monitor. Reach her via email at gro.r1754763445otino1754763445menia1754763445meht@1754763445ahtna1754763445mas1754763445.