Gravity is a friend of wastewater treatment plants, which is why the facilities are typically placed at low elevations, often along Maine’s extensive coastline.

Placing them in low-lying areas makes it easy to collect wastewater from uphill sinks and toilets. And placing them near waterways makes it easy to discharge filtered and disinfected water, or effluent, back into our rivers, reservoirs and harbors.

Many wastewater facilities in Maine and across the country were built after the Clean Water Act passed in 1972, meaning some are now 50 years old. They need upgrades not only given their age, but because of threats posed by climate change. Coastal facilities now see regular flooding during storms and high tides.

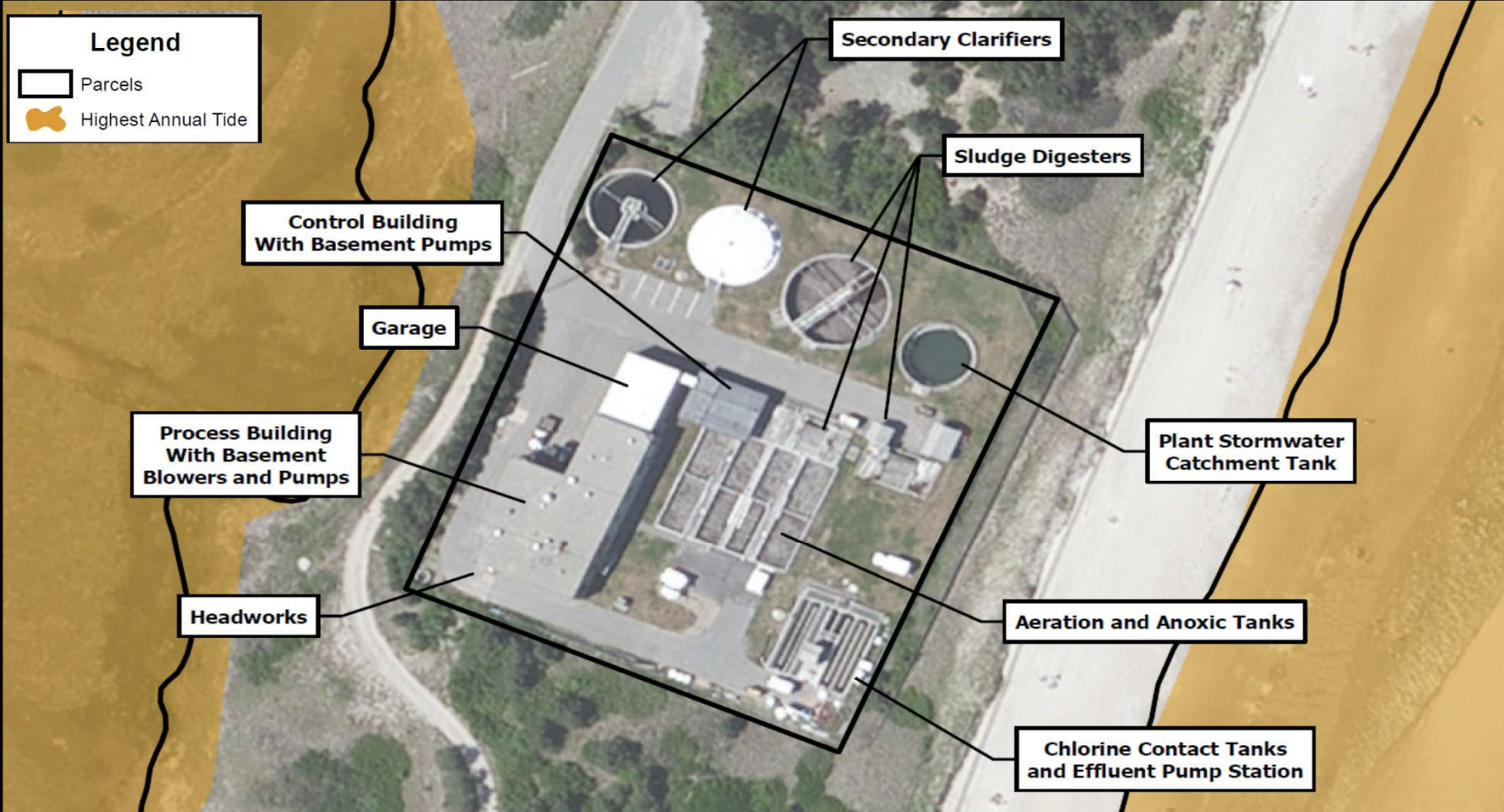

“Floodwaters can damage or destroy pumps, blowers and electronics kept in basements,” said Robert Lalli, the Wiscasset wastewater treatment plant superintendent. “And if salt water gets into sewage aeration tanks, it can disrupt the microbiology necessary to break down sewage and other hazardous compounds. Untreated sewage can then overflow into waterways, harming wildlife and those who fish for a living.”

It can also put Maine’s sources of drinking water at risk.

With the help of $40 million in federal funding, Maine communities are finding new ways to deal with threats to their wastewater plants.

The most common approach is to elevate tanks and buildings, and make other structural improvements that protect facilities from sea-level rise. This is happening all along the state’s coastline, from Kittery to Eastport.

In Machias, for example, a new pump station will keep the plant operating during heavy rains, which will help prevent sewage overflows like those that caused clam flat closures on the Machias River.

“More and more intense storms are working against us,” said Mike Riley, the combined sewer overflow abatement coordinator at the state Department of Environmental Protection. “But the new pump station, which will hopefully be up and running by the end of this year, will significantly reduce, if not prevent, overflows.”

The nearly $3.6 million project was paid for largely through a DEP grant.

Machias also plans to add a combination of seawalls (vertical or near-vertical walls) and berms (raised and sloping banks), which will protect the facility and downtown streets while creating a scenic river walk. This project is in the designing and permitting phase, said Dr. Tora Johnson, who runs a GIS Lab at the Machias-based Sunrise County Economic Council.

Portland, meanwhile, is installing four underground tanks that will hold millions of gallons of stormwater and wastewater, and keep its facility from backing up — and sending untreated wastewater into the nearby tidal basin, Back Cove.

“This pollution-control effort has been in the works for some time,” said Bill Boornazian, Portland’s water resources manager. “But the need is growing due to sea-level rise and regular flooding.”

“The biggest climate change challenge we have is intense rain events in the winter when the ground is frozen,” Boornazian added. They make the ground “like asphalt,” he said, noting that the new tanks will improve drainage and reduce flooding of city streets.

Portland is scheduled to start using the new tanks in December, said Brad Roland, a senior project engineer with the city’s Department of Public Works. He said the project, which began before the pandemic, will cost around $42 million.

The Ogunquit Sewer District plant sits on a long, sandy peninsula between the Ogunquit River and the ocean. At this picturesque and vulnerable spot, a second story is being added to a garage for increased office space, and the existing tank walls will be made taller, according to Philip Pickering, the sewer district superintendent. The electrical equipment and generator at a nearby pumping station will also be elevated.

But it’s only a temporary fix. A 2012 study found there was “no practical solution” that would allow the site to host a wastewater treatment plant beyond 2052 because of the “elevated risk from sea-level rise, flooding and shoreline erosion.”

Ogunquit is raising funds to relocate the facility about two miles west of its current location. The move, likely to occur between 2040 and 2055, is estimated to cost $30 million.

Facing a similar dilemma, Wiscasset officials hope to move the town’s facility as soon as a suitable site is found. The current location on the Sheepscot River is “the lowest point in Wiscasset,” said Lalli.

“We’ve had salt water come through our gates and into our tanks,” he said. “A seawall is impractical. If we moved up just three or four blocks, we’d be fine.”

If officials find a site close to the current location, it will cost around $35 million. If the new site is farther away and requires additional pipe laying and pumping stations, Lalli said, the cost could rise to at least $45 million.