One corrections officer spread a false rumor that the new female officer at the state prison in South Windham was a stripper.

Another one called her “Genitalia,” instead of her real name, which also began with a “G.”

She was asked by a colleague if he could measure her buttocks. When she said no, he did it anyway. She was asked about her favorite sexual positions and to describe her breasts.

When her complaints were not taken seriously, she quit her job and filed sexual harassment and retaliation complaints against the Department of Corrections with the state Human Rights Commission, detailing what she said happened to her in a sworn statement.

The state settled the case. Cost to taxpayers: $20,000.

A beginning state trooper – a male – was placed under the supervision of a male sergeant, who took him on assignments to secluded locations, rubbed the trooper’s inner thigh and talked about skinny-dipping. The sergeant gave the trooper a rug and told him how good it felt to lay naked on it, according to the trooper’s sworn statement.

The trooper got a transfer, but the sergeant called him regularly, making comments about penises and oral sex and suggested they take a naked sauna together.

The trooper filed a sexual harassment complaint and the state settled the case out of court. Cost to taxpayers: $50,000.

A park manager says she was threatened with losing her job after she refused to move out of her state housing so her boss, the commissioner of conservation, could use it to entertain guests. He denied the whistleblower and sex discrimination complaint. The state settled out of court for $30,000.

A corrections officer was threatened in a website run by anonymous corrections staff called the Rat’s Ass Gazette after she complained of sexual harassment. Cost to taxpayers: $137,500.

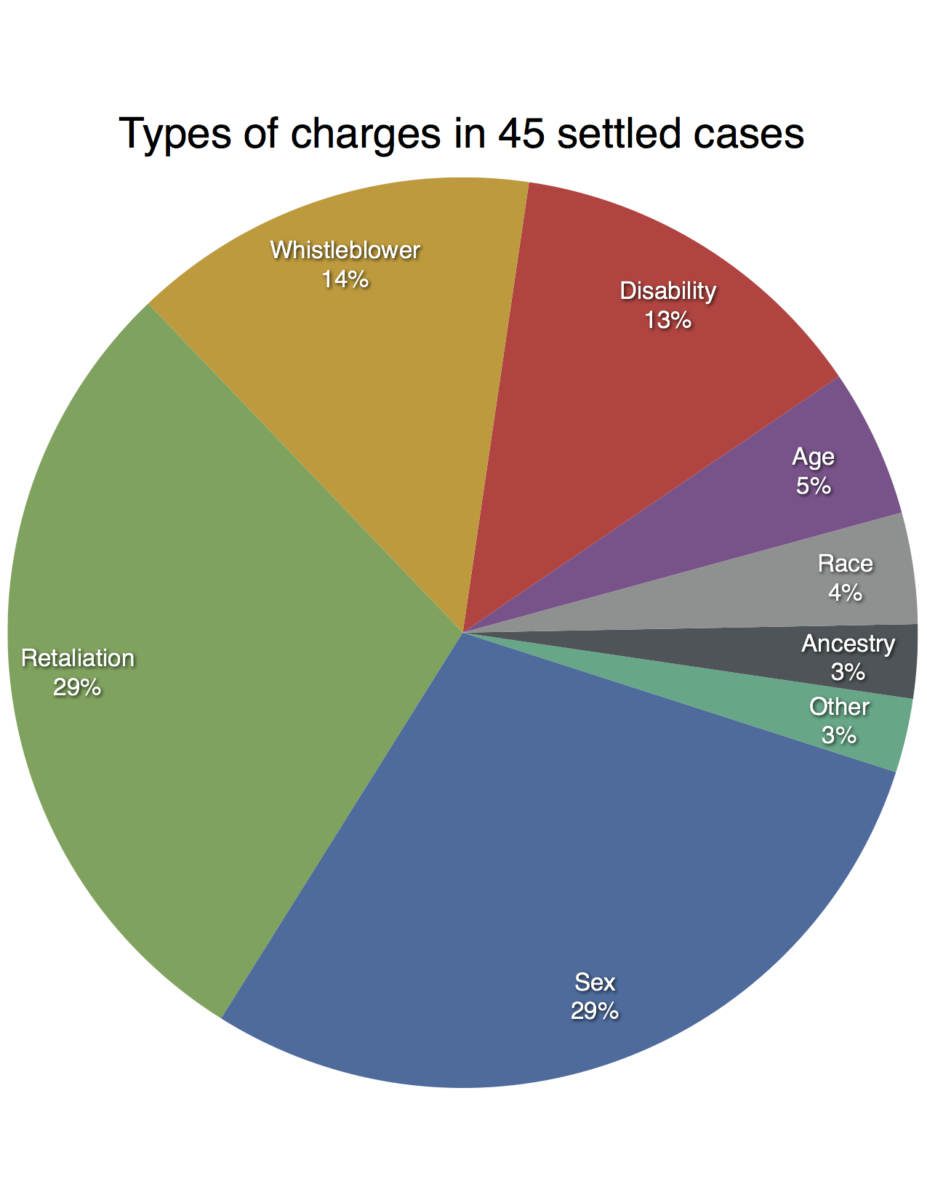

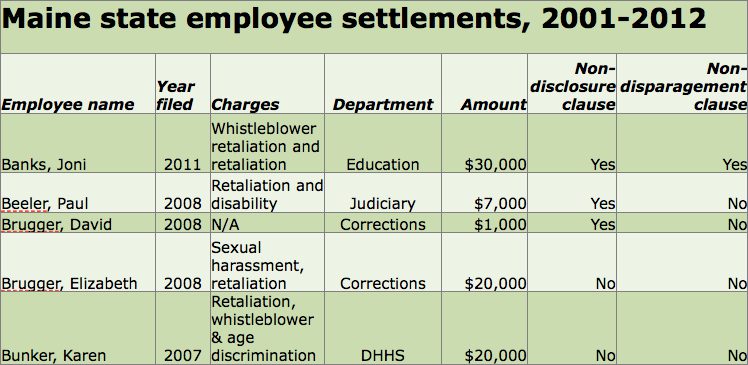

Retaliation in the human services department, disability discrimination in Public Safety, sex discrimination in Corrections and on and on for a total of 45 such cases settled by the state in the past 10 years.

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting investigation is the first known full accounting of the extent and cost of employee discrimination cases settled by the state. (It excludes settlements made by the University of Maine System because they are not handled by state government.)

By analyzing documents obtained through the Freedom of Access Act from the Attorney General’s office, the Maine Human Rights Commission and the state’s internal insurance office, the Center has found:

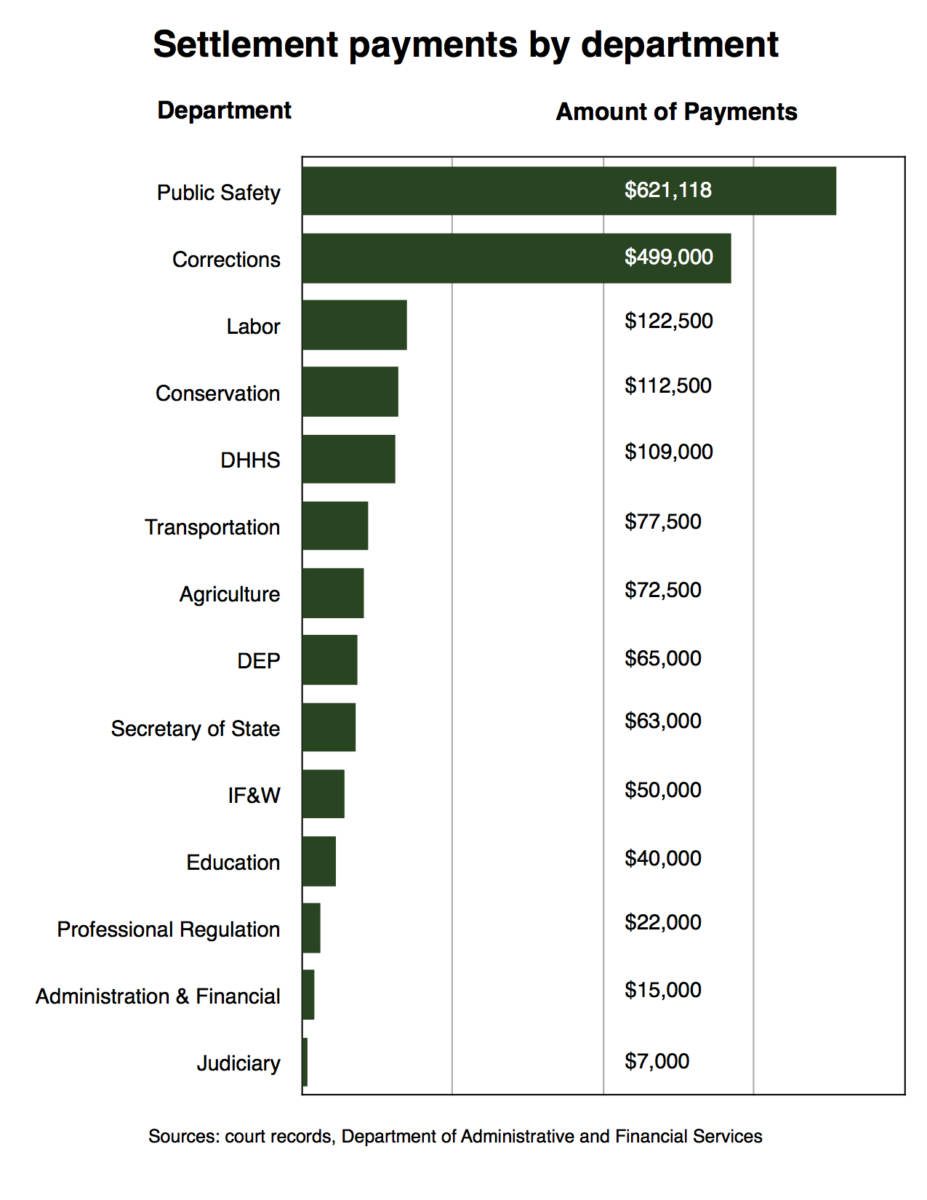

* The cost to taxpayers for a range of alleged bad behavior by state employees towards their fellow workers in the past 10 years: $1,846,118.

* The state has spent about another half-million dollars to defend itself in the cases.

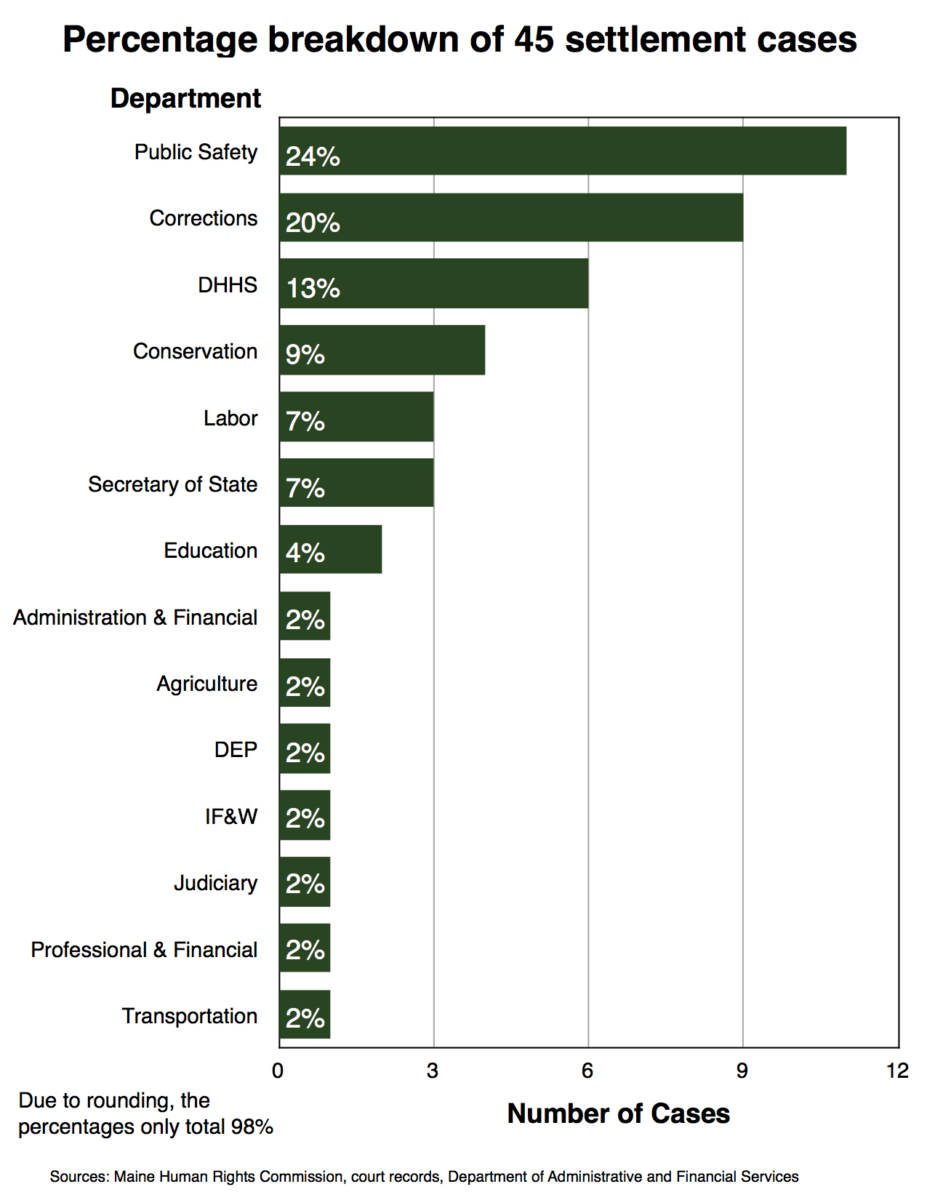

* Forty-four percent of the cases came from two law enforcement departments – Corrections and Public Safety, home of the state police. Those 20 settlements cost taxpayers more than $1 million.

* The most common charges were sexual harassment, sex discrimination and retaliation, the latter often in response to filing an original charge.

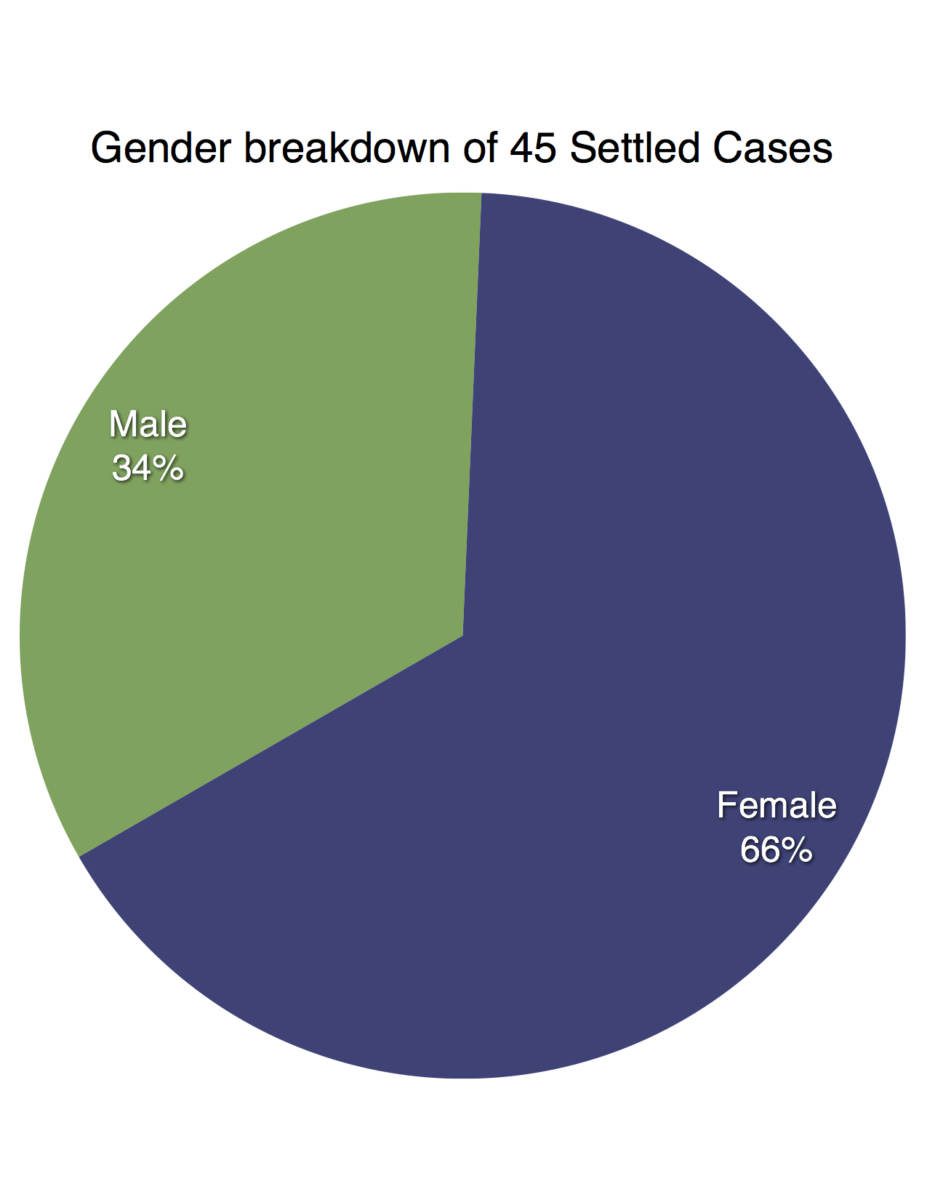

* Of the 19 state employees who said they experienced sexual harassment or discrimination, two-thirds were women.

* In all of the settlements, the state admitted no liability.

No tracking by department

State law requires that all new employees receive sexual harassment training their first year in the job, according to Assistant Attorney General Susan Herman.

Herman said her office does not track the claims to find out where there might be a chronic problem.

“We have not analyzed the data by department,” she said.

When it comes to punishment for employees found to have harassed a fellow employee, Herman said any action is up to the commissioner of the department involved.

Public records do not include any disciplinary action that may have been taken in the 45 cases.

David Webbert, an Augusta lawyer who specializes in employment cases – including representing state employees – doubts training alone would solve the problem.

“No amount of civil rights training can overcome discriminatory attitudes at the top of an organization,” he said. But, he added, “The state could greatly reduce lawsuits and money settlements — and improve workplace productivity — by basing the evaluation and promotion of managers in a significant part on their record of promoting civil rights and eliminating harassment and discrimination in the workplace.”

Some details kept secret

The settlement agreements — legally binding documents signed by the state and the employee — are often written in a way that prevents full public disclosure.

For example, in 34 of the 45 cases, in return for the settlement, employees and the state agreed not to disclose the terms of the agreements.

The secrecy goes even further in the 21 cases that have non-disparagement clauses. Typically, they state, “Both parties agree that they will not disparage the other.”

That means, for example, the park manager who received the $30,000 was barred, then and forever, from speaking badly of her boss, Patrick McGowan, commissioner of conservation. (McGowan ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2010.) And no one in state government can disparage the park employee, either.

However, the Human Rights Commission and court files — public documents — often contain some details of the cases, although the Attorney General’s office redacts from the commission reports the names of third parties under state confidentiality laws. That means, for example, that the names of supervisors are not public.

In 82 percent of the cases, the process began with the employee filing a complaint with the Commission. (The others filed civil suits.) The Commission, a state agency established in 1971, investigates complaints of discrimination from public and private employees.

“This discrimination costs the state a lot in employee morale, time, and efficiency, and in money towards lawyers’ fees and recovery for the successful employee- litigants,” wrote Amy Sneirson, the Commission’s executive director, in an email to the Center.

“What the public could take away from this data is that bad behavior at work has a tremendous impact,” she said, “including an impact on the taxpayers who ultimately subsidize settlements by state agencies.”

Webbert, the employment attorney, said, “Based on representing many state employees … I have observed that the worst problems … are in the law enforcement areas … These are the areas that most often have leadership that sends a message to the rest of the organization of hostility or indifference to civil rights requirements, especially equal treatment and respect for women and workers with same-sex sexual orientation.”

Payments come from state budget

The settlement payments don’t come from traditional insurance; the state is self-insured for these cases. That means the cash comes directly from the state budget.

Each state agency is assessed an annual amount that goes into the state’s self-insurance budget, which is about $1 million.

The departmental assessment is based on the number of employees and the claims history.

The Department of Corrections, which runs the state’s prisons, is currently assessed $101,000, 10 percent of the total self-insurance budget, while it only has 6.8 percent of the total number of 18,500 state employees. The reason is the disproportionate number of settlements in Corrections.

The department’s employee discrimination settlements were one reason the legislature asked its investigative agency to evaluate Corrections in 2009.

The Office of Program Evaluation and Accountability (OPEGA) report was titled, “Organizational Culture and Weaknesses in Reporting Avenues Are Likely Inhibiting Reporting and Action on Employee Concerns.”

The report said intimidation, retaliation and distrust within Corrections kept a lid on exposing internal problems. Combined, the practices “appear unethical” and “expose the State to unnecessary risks and liabilities.”

OPEGA’s study went to the legislative Government Oversight Committee, which directed Corrections to develop a “strategic action plan” that addressed the problems.

But OPEGA’s executive director, Beth Ashcroft, said from 2010 until this year, “it was difficult to tell how much progress was being made and whether it made a difference.”

She said when the administration of Gov. Paul LePage took over in 2011, “We learned that wasn’t a whole lot of progress that had been made. The new administration took it on, and they’ve updated the action plan and reported to the Government Oversight Committee two or three times since.”

According to two long-time state Human Resources officials, in the past two years there has been a push in state government to deal more effectively with discrimination and harassment.

Laurel Shippee, coordinator of the Equal Employment Opportunity office, said the attorney general’s office has added a trainer, and ensured that a legal expert conducts all of the training in harassment and equal opportunity.

She said the change was at least partially a reaction to the costly settlements.

She also praises a new attitude in Public Safety, which she traced to a new head of the state police, Col. Robert Williams.

Joyce Oreskovich, human resources director for the state, said, “Bob is much more interested in fairness and equity” than previous management.

Oreskovich and Shippee trace the changes to a meeting with Gov. LePage early in his tenure. They told him their priority was fixing the problems that discouraged women from applying for state law enforcement jobs.

Oreskovich said LePage “just looked at me and said, ‘Do It.’ ”

The two women said there’s been a shift in Corrections, also, under Commissioner Joseph Ponte, who took the job in early 2011.

“Very early on, Commissioner Ponte began talking about changing the culture in Corrections,” said Shippee. “I am definitely seeing an interest in swift and firm discipline that they’re not wavering on. That is one of the best ways to get across that we’re taking this seriously, if people are held accountable for these behaviors.”

One of the incidents that let to the OPEGA study was the 2008 case of Pamela Sampson, a corrections officer at the state prison in Warren.

In her suit against the state, she said she was sexually harassed by a sergeant who was later fired for sexually harassing another officer.

When she complained to management, she said they retaliated by investigating her on charges of sexually molesting inmates.

She was later cleared, but she ultimately left the state job because of the stress and concern for her safety.

The state denied she was sexually harassed and that the sergeant was dismissed for harassment, but admits the charges against her “were not substantiated.”

The state settled her claim in 2007 for $66,000. Only six of the 45 claims were settled for a higher amount.

Although Sampson’s settlement has a non-disclosure and non-disparagement clause, she was willing to be interviewed.

“If you speak about anything against these guys (in Corrections), it’s not good,” she said. “They use a lot of retaliation. That’s why everything was thrown out in my case: They tried to create a false investigation against me.”

Sampson now lives in Bangor and is looking for a job in security.

“I wanted to continue working at my job, and I miss it very much,” Sampson said. “It’s just really hard right now.”

Disclosure: David Webbert has been a donor to the Center.

State paid $30,000 to park manager who said McGowan wanted her out

Marilyn Tourtelotte worked for the Department of Conservation as a park manager for over 15 years. She had also been a game warden for the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and served as co-chairman of the Land Use Regulation Commission.

She was named manager of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, a position in the Department of Conservation, in 1999. The position came with a requirement to live in the waterway, and Tourtelotte was assigned a year-round residence.

In a sworn statement Tourtelotte filed with the Maine Human Rights Commission, she said that on Jan. 31, 2006, Commissioner of Conservation Pat McGowan’s secretary emailed her “inquiring how she could reserve my assigned residence of use by the Commissioner and his guests.” Tourtelotte’s supervisor said that wasn’t allowed because the residence was her home.

Tourtelotte’s statement describes how, in a subsequent phone call, McGowan’s secretary repeated McGowan’s demand that he be allowed to use Tourtelotte’s residence. When she refused, the secretary said, “He wants you to move out.”

That same day, Tourtelotte wrote, “the Commissioner telephoned my supervisor, (name redacted), and told him that I should be ‘cooking for them’ and showing ‘north woods hospitality’ by allowing his party to use my residence.” McGowan also called her supervisor later that day, and both Tourtelotte and her supervisor talked with him.

“When I mentioned that he and his party could not use my residence, he said ‘we’ll see about that,” Tourtelotte wrote.

Tourtelotte wrote that her supervisor later told her “the Commissioner had a ‘target on my back’ and that word came down from the top that he was told to do whatever was necessary to get rid of me. “

Subsequently, the department began an investigation into Tourtelotte based on an “outside complaint.” That investigation, covering a seven-year period, ended with a two-week suspension, which she served.

Tourtelotte then filed a complaint with the Commission in July, 2007, alleging sex discrimination and whistleblower retaliation.

“I believe my suspension … occurred as a result of unlawful sex discrimination because I am a woman, because I am the only female Park Manager with assigned housing and because I would not give up my residence so that it could be used by the Commissioner and his friends. No male Park Manager has ever been asked to give up his residence for such a purpose.”

McGowan, in an interview, said Tourtelotte “was never asked to move out and make accommodations for me.”

“We were doing a film on the 40th anniversary of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, and I asked if the film crew could stay in the cabin near the Churchill residence. It was not her residence; it’s an outbuilding,” said McGowan. “It’s not an issue, her statement was so ridiculous.”

McGowan claimed that Tourtelotte recanted her statements about being asked to move out and cook for him and his friends.

“No, I did not take them back,” said Tourtelotte in a recent interview.

McGowan said that the investigation of Tourtelotte was justified by facts, not retaliation:

“Her personnel actions were brought about by complaints by people who were under her supervision,” said McGowan. “There were some very serious violations alleged by her employees.”

“The investigation was thrown out,” said Tourtelotte, who added that any record of it was “supposed to be destroyed.”

“There is potential for a lawsuit if anybody talks about that investigation,” said Tourtelotte. “I proved that what was in it was false information.”

The department settled in July, 2008 with Tourtelotte for $30,000 and provided her a comparably paid job in the Land Use Regulation Commission. The settlement, signed by McGowan, features a non-disclosure clause and includes the following phrase:

“It is further understood and agreed that this settlement is a compromise of disputed claims and that this Release and Settlement Agreement is not to be construed as an admission of any kind by any party or an admission of liability on the part of the Releasees, by whom liability is expressly denied.”

McGowan announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for governor in January, 2010.

From the case files: a bad back, sex wagers, kisses and payback

The following examples of discrimination charges were taken from complaints filed with the Maine Human Rights Commission and court documents.

$9,000 to settle case of an alleged bad back

Charles Graten was a customer service representative in the Secretary of State’s division of motor vehicles who said the office was not making accommodations for his disability. He cited neck, back and leg pain due to his work station.

Records show the state made numerous attempts to modify the work station for Graten, who they noted weighed 320 pounds. He took a leave of absence; when it was over, the department told him to return to work or provide a doctor’s note. When that was not provided, he was dismissed.

A commission investigator concluded that Graten’s physical problems did not constitute a legal disability. His supervisors, according to the report, responded promptly at times, other times were “genuinely confused” by the situation and the doctors involved “presented starkly contrasting opinions.”

In the end, the Commission found no basis that Graten was illegally discriminated against.

Nevertheless, the state settled the case for $9,000.

Toxic demotion costs state $65,000

Andrea Lani worked in the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), running the program that educates the public about toxic chemicals.

According to her retaliation lawsuit against the state, in 2011 she was demoted by top appointees of Gov. Paul LePage because she testified against a bill supported by the administration. Lani believed the bill would weaken the Kid-Safe Product Act.

Lani, who said she took a vacation day to testify, said state law prohibits taking action against an employee based on testifying before a legislative committee.

DEP Commissioner Patrica Aho ordered an investigation into whether Lani used department resources to develop her testimony, according to a story by the Bangor Daily News.

The lawsuit states Lani was cleared of that allegation, but was later reassigned to a clerical job and her old job was filled by a less qualified person.

The settlement not only paid Lani $65,000, but also required the state to provide training to supervisors about the state law barring retaliation for giving testimony.

Bets on her sex life

The corrections officer was hired in 2001, one of the few females in that job. (The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting is withholding the employee’s name from this portion of the coverage to protect her privacy due to the salacious allegations.) Among the claims in her sexual harassment lawsuit:

* Some fellow officers “had a betting pool about whom and when (she) would sleep with first,” including inmates.

* Rumors circulated that she “was willing to perform fellatio for $20.”

* She claimed her supervisor was trying to force her out because she had complained about the sexual harassment. One example she cited involved a report she said was designed to undermine her: that she witnessed a male officer demonstrate how he could touch his nose with his tongue.

According to the report, she commented: “I can’t believe he can do that. I think I’m in love.”

In her court filing, she claimed she never made that remark. Instead, she said the officer was ordered by the supervisor to fabricate the comment. In the state’s response to that charge, it agreed that the officer admitted he did not hear the offensive comment, but denied that he was ordered to make up the claim.

The female officer eventually quit the department when she said behavior and comments by officers and a supervisor created “a hostile work environment.”

While the state contested some of her allegations, it eventually paid a lump sum cash settlement to her for $65,000.

The kissing supervisor

From 2007-2008, Trish Smith was a juvenile program worker at the Department of Corrections Mountain View Youth Development Center in Charleston. Her lawsuit against the department for creating a hostile work environment and retaliation details the case of a supervisor known for his advances towards female employees.

The suit, citing Smith’s allegations and also affidavits from other employees, is unusual in that the state admits some of the behavior.

Some examples of what the state admitted:

* The supervisor “made inappropriate comments and jokes of a sexual nature, inappropriately touched and hugged and attempted to kiss” Smith and demonstrated similar behavior with other employees.

* In March, 2004, the supervisor “intentionally snapped” the bra of an employee.

The state denied some of the other claims by Smith, including that management failed to keep her supervisor away from her, as they had promised to do after she complained.

Smith’s suit said she felt forced to resign because of the unwanted contact with the supervisor.

The state settled for $69,500.

There is no public record of what happened to her supervisor.