Most of the people who fill your prescriptions are honest and do their job well.

But some of those people in white smocks are thieves, drug addicts or both.

The typical image of drug thieves is armed robbers with masks holding up pharmacies for pills to feed their habit. But stealing happens on the other side of the pharmacy counter as well.

An investigation by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting of state disciplinary records has revealed that from 2003 to 2013, 16 pharmacists and 41 pharmacy technicians lost their licenses for pilfering drugs from pharmacy shelves or even from the patients whose prescriptions they filled.

More than one-third of the prescription drugs stolen from Maine pharmacies are taken by employees. And according to industry experts, the pharmacy professionals who are caught for theft represent only a fraction of those who actually steal.

One pharmacy technician stole 737 tablets of Suboxone, a methadone-like medication used to treat drug addiction; 8,724 tablets of Hydrocodone, a narcotic pain reliever; 600 tablets of Phentermine, a diet drug that’s also a stimulant; and 410 tablets of Alprazolam, used to treat anxiety and panic disorders.

In another case, a pharmacist forged a prescription for Vicodin — hydrocodone combined with acetaminophen — to his bulldog, Stella Rose, then dispensed the pills to himself and “ingested two pills for the half hour car ride to his home in Rumford,” according to the state records. Later, the same pharmacist forged Stella Rose a prescription for a potentially addictive anti-anxiety and tension headache drug called Fioricet.

Almost every Maine pharmacist and pharmacy technician caught and disciplined for stealing medications said they did it to feed their drug habit. And they did it because it was there.

“In a recent survey of recovering pharmacists, participants noted that easy access to the drugs encouraged them to take them and likely led to their addiction,” wrote the American Pharmacists Association in 2013.

It’s dangerous when someone high on drugs dispenses medication.

“If I’m John or Jane Q. Public, I certainly don’t want an impaired pharmacist or pharmacy technician filling my prescriptions,” said John Burke, commander of the Warren County, Ohio Drug Task Force and a nationally known expert on drug theft.

“I don’t want to have a drug in my pill bottle that I shouldn’t have gotten.”

Greg Cameron, a pharmacist and Husson University professor who worked for 15 years as an investigator for the Maine Board of Pharmacy, said, “If you’ve got a pharmacist that’s working impaired, the public’s going to be at more of a risk for the pharmacist making mistakes because he’s not of sound mind and judgment.”

The majority of pharmacy thefts over the past decade involve two of the most abused drugs in the nation: Hydrocodone and Oxycodone, another narcotic pain reliever.

“The vast majority of people you’re talking about are addicts. All those drugs are there, there are ways to manipulate audits, they have direct access, walk in the door and grab a pill bottle … The opportunity, I think, is huge,” said Burke.

Kenneth McCall, head of the Maine Pharmacy Association and a professor at the University of New England School of Pharmacy, said that while pharmacy employees may well have addiction problems and steal, so do other members of the health professions.

“Pharmacy for a long time has known of the real problem of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians that have addiction and medical problems with addiction.

“In the broad picture, to really address this issue of substance abuse and misuse of prescription drugs, we can’t focus on one access point in our communities,” said McCall. “We have to think systematically, holistically and broaden the scope.”

There are 1,866 pharmacists and 2,461 pharmacy technicians in Maine, so the percentage of pharmacy employees caught stealing drugs is small.

But much of pharmacy drug theft likely goes undiscovered and unreported. Assistant Attorney General Michael Miller, who advises the Pharmacy Board and formerly ran the Maine attorney general’s health crimes unit, said, “I believe there’s a lot of criminal conduct that does not get caught at all.”

Or, as one addicted pharmacist told scholars investigating pharmacists’ drug abuse, “Let’s face it, we’re the ones who got caught. There’s a whole lot of people out there that never get caught. A lot more than you’d care to know about.”

The unnamed pharmacist, who was quoted in a study published in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, said, “I knew of people who should’ve gotten caught. But, you know, we don’t tell on people. …That’s part of the code.”

Pharmacist let mother dispense drugs

A pharmacy technician does much of the routine work involved in filling prescriptions, from taking refill orders, receiving prescription faxes from doctors’ offices to actually filling prescription bottles. Each filled prescription is supposed to be checked by a licensed pharmacist before it is given to a customer. Pharmacy technicians do not need more than a high school diploma to be licensed and are trained on the job.

A pharmacist has at least four years of college education in pharmacy or may have a pharmacy doctorate. In Maine, only pharmacists can counsel customers, and each pharmacy is required by law to have a “pharmacist in charge” to oversee its daily workings.

When pharmacy technicians and pharmacists get into trouble, the state Board of Pharmacy considers their case and metes out punishment. The records of those cases are posted online, and provide a detailed picture of the bad behavior in the pharmacy profession.

Some examples:

• The pharmacist disciplined for 15 prescription misfills either made by her or by pharmacy staff under her supervision. They included giving a stool softener to someone instead of an antibiotic and tripling the dosage of a six-year-old’s medication, causing the girl’s teacher to call the mother to say the child was “disoriented, walking into walls, and ‘hyper.’”

•The pharmacist who got in trouble because he had practiced for more than eight months without a valid license.

•The pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who were investigated and disciplined because they failed to disclose their criminal history when applying to practice in Maine.

•The pharmacist who owned a pharmacy in Waterville, took a job elsewhere and put his mother in charge of the Waterville pharmacy, where she dispensed medications — even though she wasn’t a pharmacist.

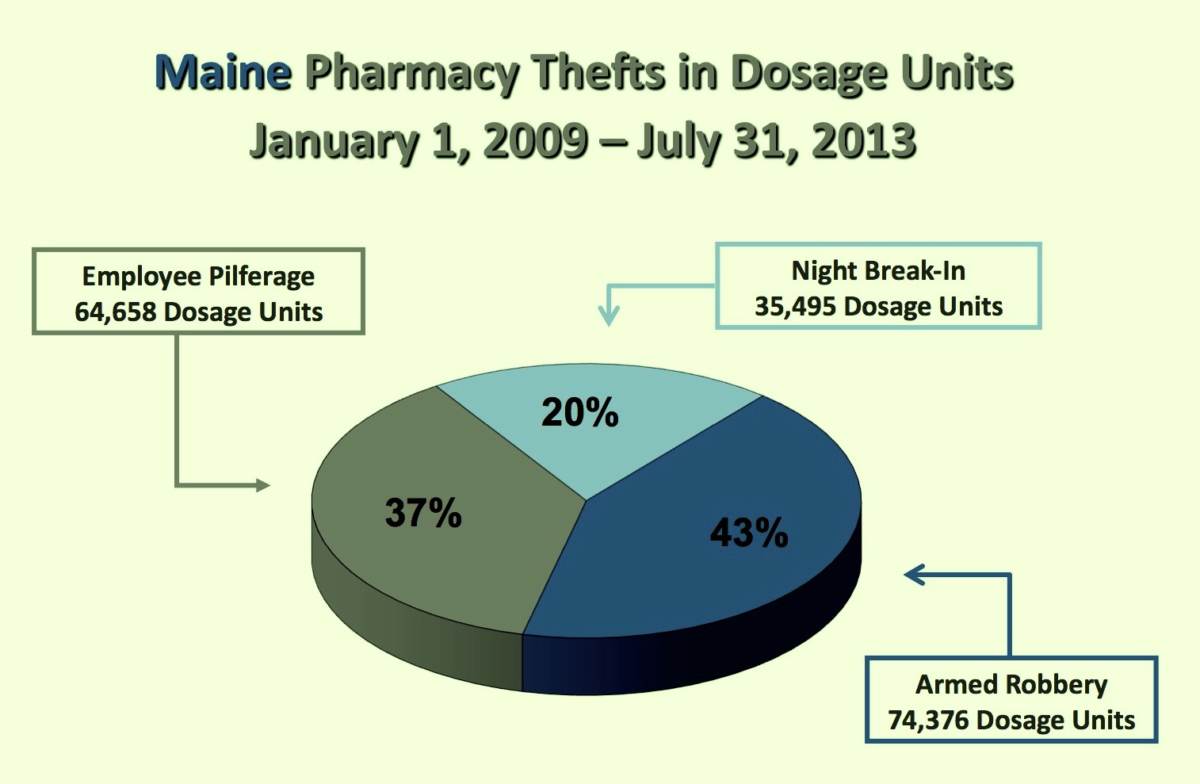

Among the largest number of cases are the ones where pharmacy employees steal drugs. It’s not a problem unique to Maine: The US Drug Enforcement Administration says that for the last three years, “employee pilferage” has constituted the largest single percentage of pharmacy thefts nationwide – 46 percent vs. 26 percent for armed robbery thefts and 28 percent for night break-in thefts. In terms of dosage units – the amount of drugs stolen – employee theft is 44 percent, night break-in is 45 percent and armed robbery is 11 percent.

Steve Sylven, the spokesman for Shaw’s, which employs 35 pharmacists and 45 pharmacy techs at its 15 pharmacies in Maine, said the company is constantly reviewing and revising its methods to prevent theft of drugs.

“Certainly theft is a pervasive issue in the retail industry and we invest significantly in our loss prevention department,” said Sylven. “While I can’t get into the methods we use to deter theft for obvious reasons, we have multiple measures in place to prevent theft which includes everything from cameras to inventory protocols.”

The disciplinary file on pharmacy technician Maria Kiyanitsa, who lost her license in 2007 after admitting to stealing “in excess of one thousand hydrocodone tablets from Rite Aid,” is representative of the many cases concerning pharmacy technicians and pharmacists.

“Ms. Kiyanitsa subsequently admitted to the Board investigator that she was addicted to hydrocodone and had been diverting hydrocodone for her own use for approximately six months by taking five to ten pills at a time from the Rite Aid stock. … Rite Aid Pharmacy #4660 reported approximately 2,900 pills missing from its stock during this period of time,” reads the record.

“Addiction is a major problem among a minority of pharmacists,” writes the American Pharmacists Association in the study materials. As far back as 1998, the association reported that 19 percent of practicing pharmacists “are occasional or regular users of controlled substances without a prescription.”

In Maine, Lani Graham, the physician who runs the Medical Professionals Health Program, said that among current pharmacists, “you would expect between 5 and 8 percent affected by substance use disorders.” There are no estimates for pharmacy technicians.

That would mean between 93 and 149 Maine pharmacists are substance abusers or recovering substance abusers. And many of them have not been identified, sanctioned or helped.

“Currently,” said Graham, “we have 13 in our program. The ones that are out there, some of them are under other forms of care and doing well.

“Some of them may not yet be in care” at all, Graham said.

They may not be in care because they’re not being detected. While 58 thefts came before the board between Jan. 1, 2003 and Dec. 31, 2012, only one new theft was brought to the board between Jan. 1 and Aug. 30, 2013.

Punishments getting harsher

Pharmacy board chair Joseph Bruno said that he believes that all, or at least most, of the addicted pharmacy staff that steal are being reported. But he also said that it’s hard to find out who’s taking drugs and stealing because identifying the abusers is difficult, despite the fact that pharmacy security has been beefed up in the last few years.

“If you have an incompetent pharmacist, it’s almost easier than someone with a drug problem. Many of these people with drug problems, they have become used to living their lives under the influence. They can function,” he said.

And currently, the pharmacy board’s investigative work is being hampered by a staffing problem.

“We’re trying to hire someone, it’s very difficult because of the state wage scale,” said Bruno. “We want a pharmacist. Seven years ago, we had two pharmacist inspectors who understood what it was like to be a pharmacist. They were replaced by two ex-police officers.”

One of those investigators left, said Bruno. “So now we have one ex-police officer who’s the pharmacy investigator. While he does a good job from an investigative standpoint, he doesn’t get a lot of the subtleties of how a pharmacy works, so he misses a lot of computer-related ‘this is where you should have looked for these things.’”

Given the current lack of investigative muscle, is the board living up to its mandate “to protect the public health and welfare?”

“Any licensing board is there for the public safety,” said Bruno. “We try to do the best we can and protect the public. One way of doing that is harsh punishment and making sure that these people are taken out of circulation.

“I think we’re doing much better than we have in the past,” said Bruno, who said fines doled out by the board are higher under his chairmanship.

Besides harsh punishment, the pharmacy board has proposed another measure to ensure that pharmacy staff work at a higher professional level than in the past.

“One of the efforts in next three to five years is everyone’s going to have to be a certified pharmacy technician,” said Bruno, which requires additional training and certification by a national board.

But, said Bruno, that won’t necessarily weed out potential drug addicts and thieves. “Just because you have a license doesn’t mean you’re not going to steal,” he said.

This was the first of two parts. Coming tomorrow: Addicted pharmacists who steal get their licenses back.