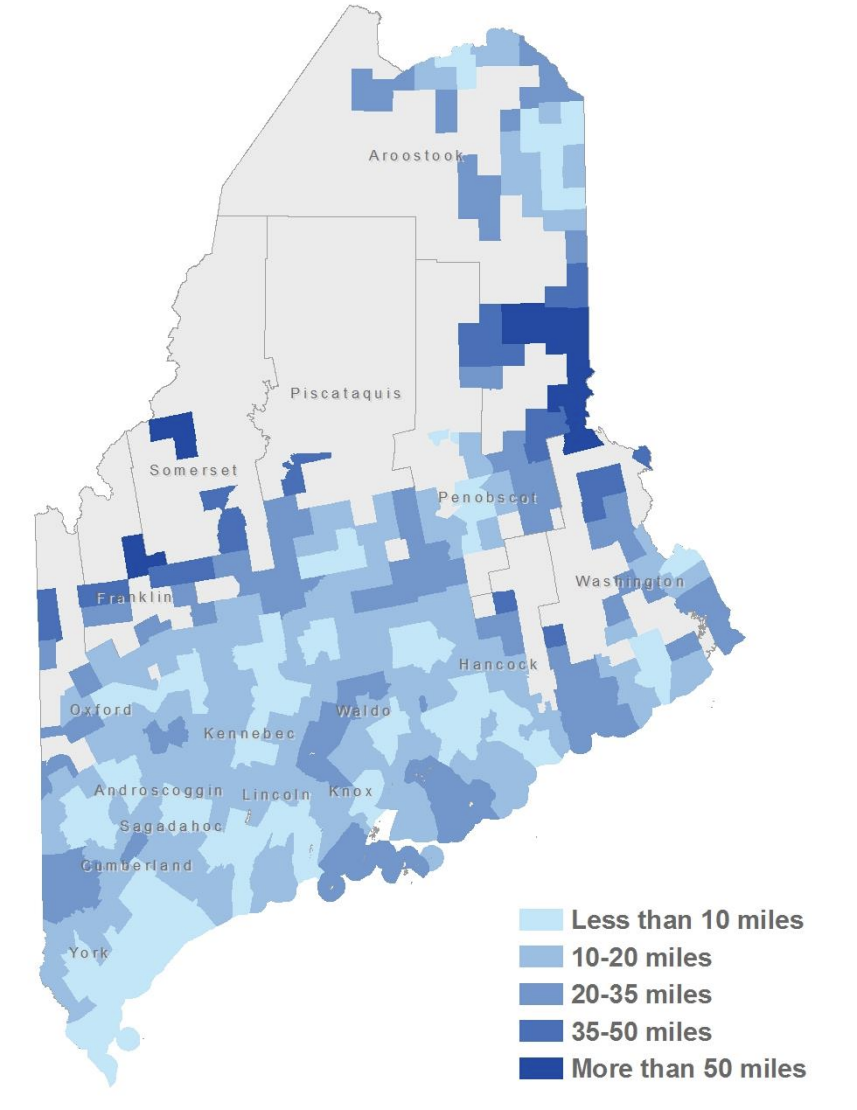

Seven years after a Maine Cancer Foundation study identified transportation as a major barrier to treatment for cancer patients in the state’s most rural areas, the same communities are still struggling with long travel times to treatments.

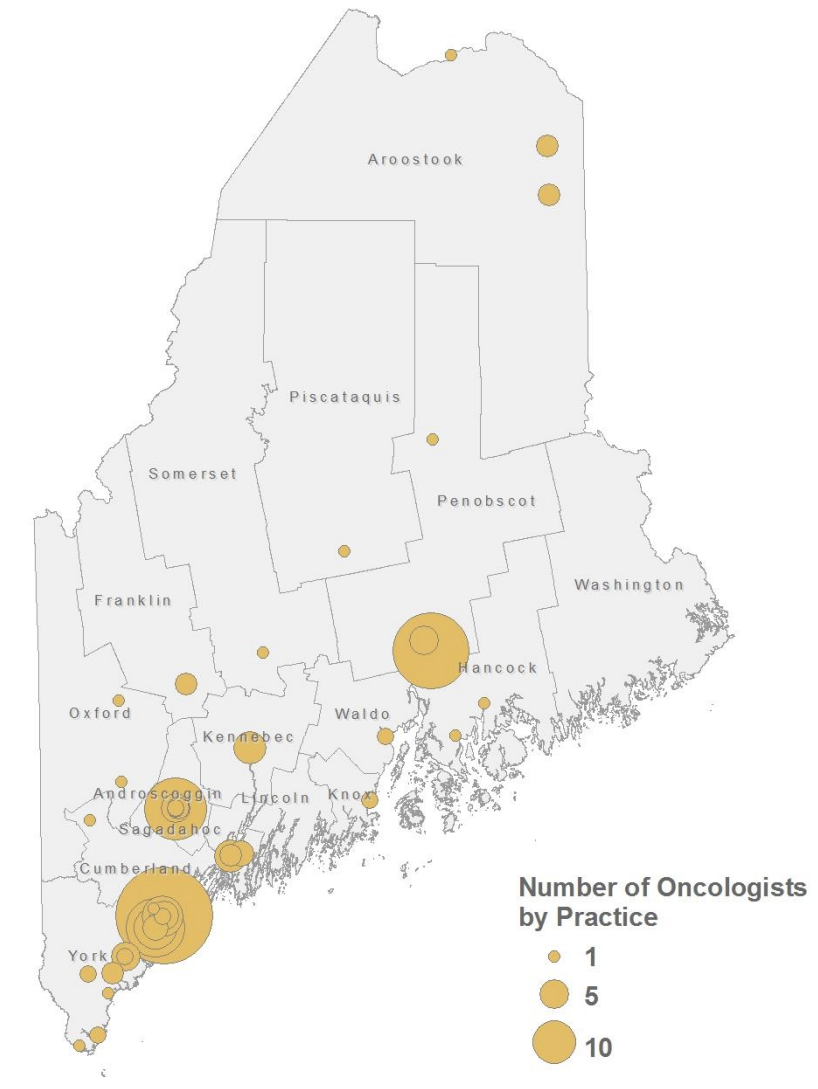

Since 2017, Maine has lost several cancer treatment centers, including the closure of the oncology practice at St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center in Lewiston in July 2023. The state has just a handful of radiation treatment sites, mostly in southern Maine.

The number of practicing oncologists has stayed roughly steady, with 76 practicing in 2017 and around 71 in 2024, according to state licensing data, and services are still concentrated in the southern region.

Aroostook and Washington county patients must travel on average more than 100 miles for inpatient cancer care, and two of the counties with the highest rates of deaths from cancer — Washington and Somerset — are without a single oncology practice.

“You’re fighting just to survive to get to your treatment,” said Angela Fochesato, the director of the Beth C. Wright Cancer Resource Center in Ellsworth.

Mainers are at a significantly higher risk of developing and dying from cancer than the national average, with rural residents most at risk, according to a recent report on cancer in Maine.

While the rate of Mainers dying from cancer decreased over the past decade, from 170 deaths per 100,000 people in 2014 to 161 in 2024, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, rates are still higher than the national average and anywhere else in New England.

There are many factors, including obesity, alcohol, tobacco use and exposure to environmental hazards such as ultraviolet rays, radon and arsenic.

Longer travel times to care can delay early detection of the disease, which has been linked to a higher likelihood of death.

Traditional treatment plans often require therapies like radiation once a day, several times per week.

For those farther from care locations, these barriers translate to hundreds of dollars in transportation costs and hours of driving. Patients who don’t have access to a vehicle, or those too sick to drive, face additional hardships.

That was the case for Kathleen Bell, who was diagnosed with stage three breast cancer in February 2013 after a mammogram screening following a skiing accident.

Bell’s husband had passed away two years earlier. She was alone and without the finances to make various appointments in Bangor from her home in Lincoln, a roughly two-hour drive round trip.

Bell underwent four rounds of chemotherapy every three weeks, lasting 5 1/2 hours each time, and received 36 radiation treatments by the end of the year.

“My keys were always in the nightstand next to me,” said Bell. “But I was so sick, I knew I couldn’t even move.”

Friends from a local book club drove her for a while. Eventually she was connected with Penquis Transportation Services, an agency with an office in Bangor contracted with the state to provide rides for certain patients with insurance through MaineCare.

“I would not have survived without Penquis,” Bell said. “Without them I would have died.”

Penquis, one of the primary transportation providers for MaineCare beneficiaries in northern and eastern Maine, made 672,339 trips last year, according to the Bangor Daily News.

More than half – around 350,000 — were part of Penquis’ Accessing Cancer Care program, according to figures provided by Steven Richard, the nonprofit’s director of transportation.

Penquis spent more than $25 million on transportation services last year alone, roughly 33 percent of its $75 million annual budget.

“Every pot of money that we manage to find, we’re able to spend pretty quickly,” said Richard.

Many rides require specialized equipment because the organization works with patients who have mobility issues or require certain medical aids.

“Sometimes they need wheelchair accessibility, sometimes they need us to actually be able to secure additional bottles of oxygen if they’re on a high consumption rate for it,” said Richard. “So those are some of the concerns (we consider).”

The Maine Cancer Foundation provides a large portion of funding for such initiatives. The director of programming, Katelyn Michaud, said the requests for grants have not slowed in her 10 years there.

“We have been investing a significant portion of funds toward transportation for cancer patients,” said Michaud, adding that Mainers would benefit from a more cohesive, statewide approach, particularly for patients who need to leave the state for care.

“It’s one thing to get a patient from Washington County to Brewer, but then it’s another to get a patient from Washington County to Portland, perhaps, or to Boston,” she said.

Staffing issues at rural hospitals also have posed challenges.

In 2022, Northern Light Cancer Care announced it would not accept new patients at its oncology and treatment center due to staffing shortages. The center, in Brewer, is a vital resource for cancer patients in eastern and northern Maine.

Northern Light Health officials said it’s back at full capacity for oncology services and recently added three medical and two pediatric oncologists.

“We’ve been very successful so that we can support and offer the (cancer) programs and additional capacity,” said Ava Collins, the vice president of oncology services for Northern Light Health. Collins directly oversees the center and cancer care programs.

“We continue to evaluate the need to strengthen our services and the care we provide to ensure we meet our mission of caring for our community,” Collins said in an email.

But the hospital system still faces deep financial challenges, with the Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center president, Gregory LaFrancois, telling employees in an email last month that it is “headed into very choppy waters,” according to the Bangor Daily News. Northern Light has cut back on services in rural areas in recent years, including closing a clinic in Southwest Harbor and shutting down a primary care practice in Orono.

Advanced trials and collaboration pioneer possible solutions

Advancements in cancer treatment options have also paved the way for patients to receive care closer to home — or even at home — by increasing access to clinical trials, which can offer expert medical care and cutting-edge treatments.

All of the state’s oncology practices receive guidance from the Maine Cancer Genomics Initiative (MCGI), a collaborative network of providers led by the Jackson Laboratory, a nonprofit medical research center in Bar Harbor.

The initiative, which began in 2017, aims to provide highly targeted cancer therapies to patients statewide.

“The biggest goal of MCGI is really to help patients get the best care as close to home as possible,” said the program director, Leah Graham.

While the initiative does not replace the need for cancer treatment centers, where patients work with oncologists to create a plan, the matchmaking process can allow some to receive treatments from home.

“The drugs that target a certain gene mutation that’s found in the cancer are oral therapies,” Graham said. “A lot of the treatments are new. Some physicians have never prescribed them before.”

An observational study by MCGI found that patients who received matched treatment through the initiative were nearly a third more likely to survive the following year than those who did not.

“The great thing about targeted therapy is there tends to be less terrible responses,” Graham said. “They’re less toxic in some ways.”

The American Cancer Society’s Road to Recovery transportation program, which has operated for over 40 years and is another option for cancer patients needing transportation to appointments, has been slow to return to normal capacity and regain lost volunteers after the pandemic.

There are also places like the Beth C. Wright Cancer Resource Center, which recently opened a second location in the small town of Baileyville in Washington County, that coordinates rides to and from appointments. The new center, which does not provide treatment but does offer wraparound services, is aimed at reaching people in the far eastern part of the state, which has some of the highest rates of cancer diagnosis and deaths.

“That is a hot spot. That’s where a lot of our patient population comes from,” said Fochesato.

Many, she added, will skip treatment if they think they can’t afford to make it.

“Some (people) will go without eating to pay for their medication … it’s not pretty,” Fochesato said.

Despite the closure of treatment centers, Cora Fahy, a breast cancer survivor and MCGI board member, said she feels more optimistic about the future of cancer survivors because of the number of local organizations working to pull together different resources across the state.

“In the nine years, even since I was diagnosed, there’s so much more offered out there,” Fahy said. “I’m very, very, very optimistic about survivorship.”