At a time when the U.S. newspaper industry is most often described as “dying” and “decimated” and publishers agree that “flat is the new up” with regard to profitability, a lot of eyes are on Maine.

They’re looking here, not because the picture is significantly brighter but because Maine’s newspaper industry is now unlike any other in the country. There’s not another state that has a single individual owning the majority of its daily newspapers, as is suddenly the case here.

In rapid-fire style – just three years – Camden businessman Reade Brower has acquired six of the state’s seven daily newspapers. The speed with which he’s done it is causing wariness among some journalists and others in Maine and an abundance of curiosity throughout the industry nationwide, about his motives and strategies.

It’s also infusing Maine with something sadly lacking in most of the newspaper world – a little dose of hope.

Critics say Brower’s near-monopoly squelches competition and homogenizes and otherwise degrades content at a time when Maine newspapers – like most papers – struggle to counteract declining advertising and circulation revenue.

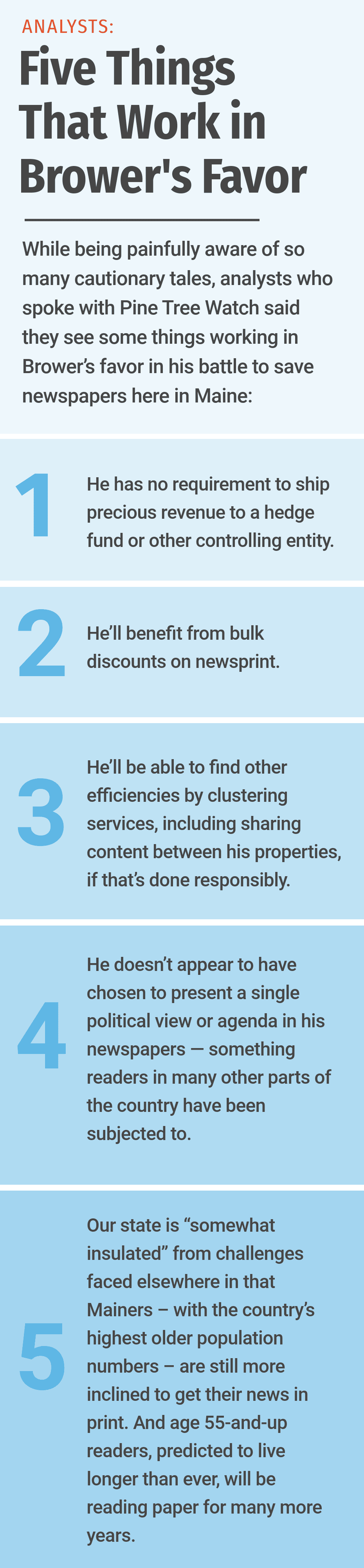

Maine’s industry also is hurting because of, among other things, an out-of-the-blue tariff on Canadian newsprint that is driving up costs by about 30 percent (which Maine Sens. Angus King and Susan Collins are fighting) and a serious shortage of newspaper carriers – to the point that Brower’s employees in Portland are being asked to pitch in and deliver daily papers.

Given the shaky nature of the industry, why would anyone want to make new investments in newspapers? What are the implications of one person having so much control? What exactly is the climate for newspapers in Maine – it’s bad, but how bad? How are people working within its limits to keep print newspapers alive? And … is this even important to do?

Over the past two months, we talked to Brower – who also owns a variety of other publications and 19 Maine weeklies – and other key industry players in Maine, as well as national and state media experts and analysts to get a handle on these questions and assess the general health of Maine’s newspapers.

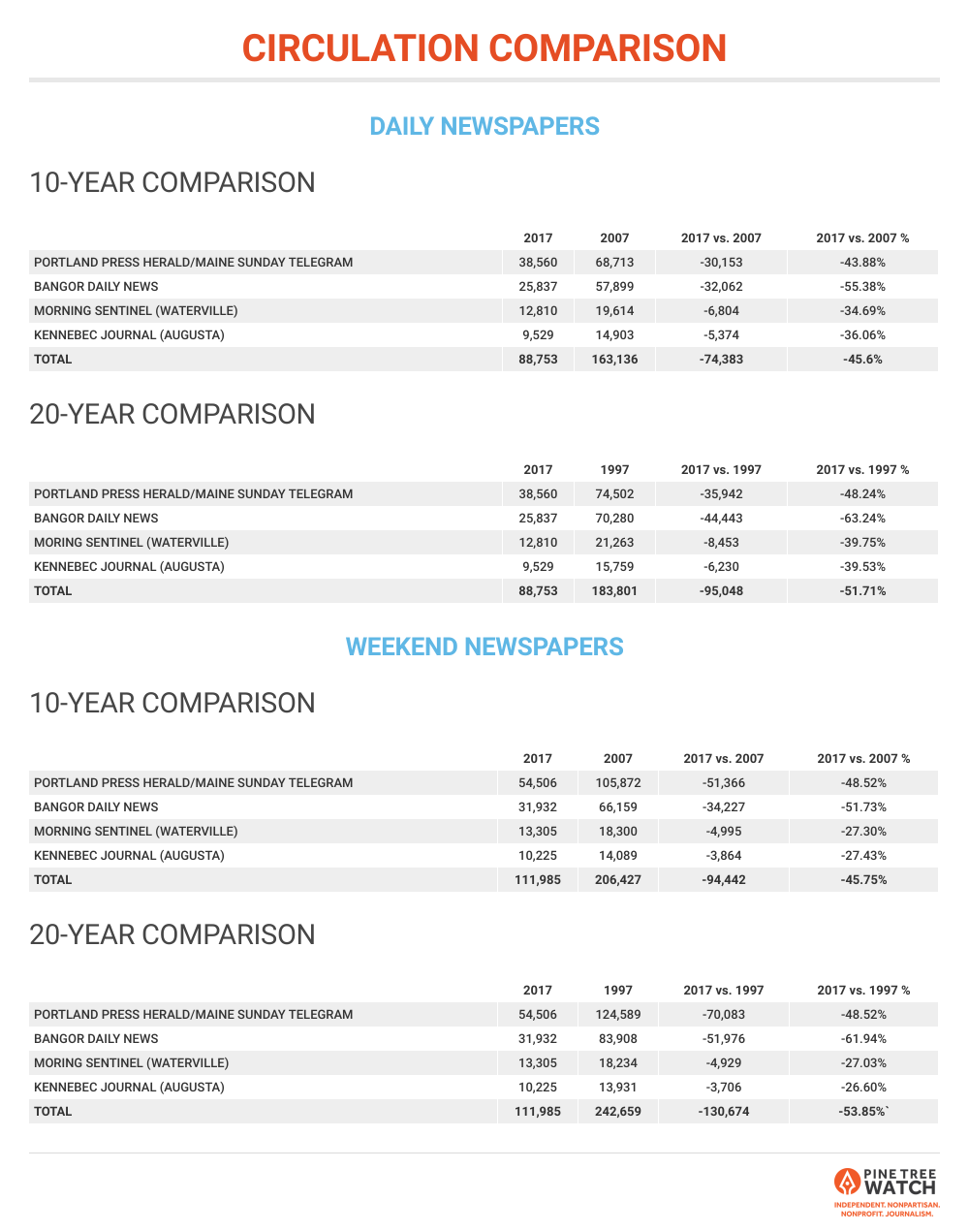

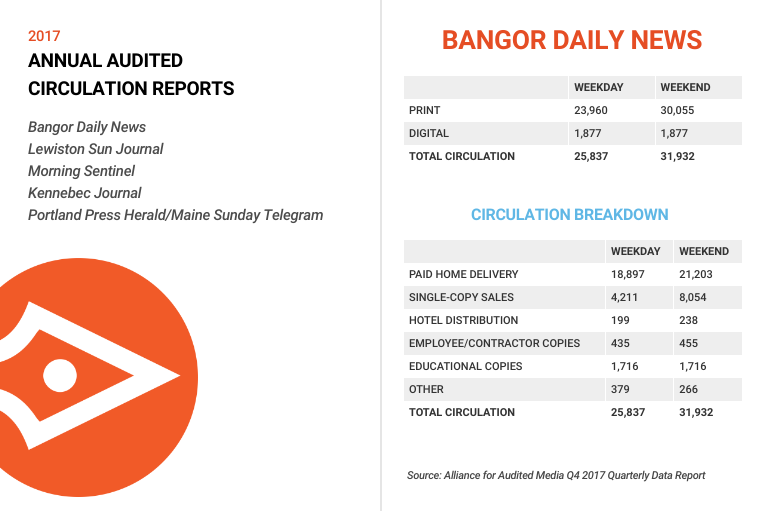

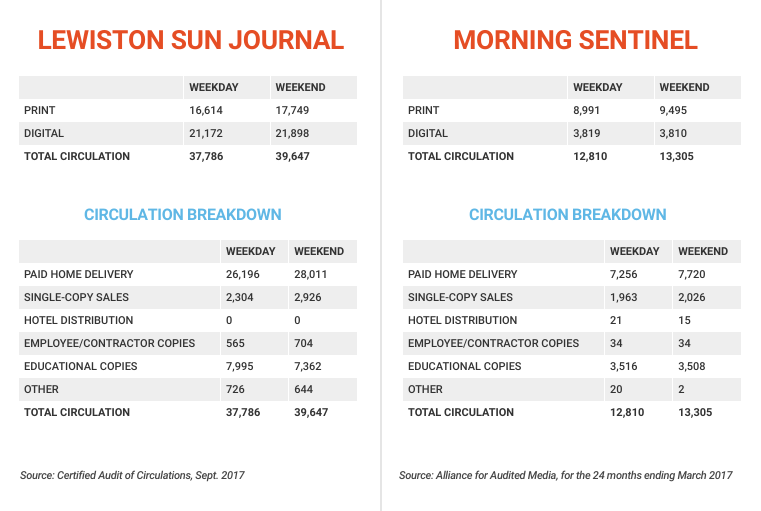

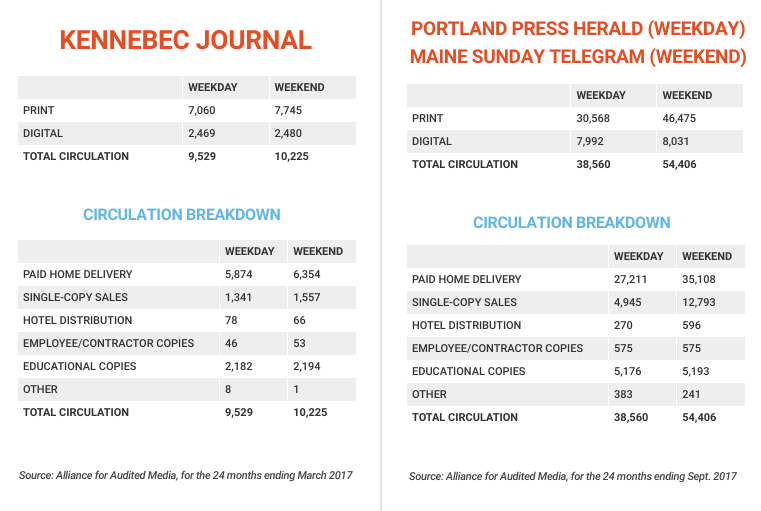

We also examined annual audited circulation reports – which newspapers file so they can provide advertisers with valid subscription numbers – for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, the Bangor Daily News, the Morning Sentinel in Waterville and the Kennebec Journal in Augusta from 2017, 2007 and 1997. Trusted reports from the same timeframe for Maine’s other daily newspapers – the Lewiston Sun Journal, the Biddeford Journal Tribune and Brunswick’s Times Record – could not be located.

These audited circulation reports reveal a stark decline in the number of newspaper subscribers over the past two decades and provide a sobering look at the deep damage the digital media revolution has done to Maine’s most traditional form of news media.

Since 1997, the audits show that the Bangor, Portland, Augusta and Waterville daily newspapers have collectively lost 51.7 percent of their weekday (Monday-Friday) circulation totals, shedding 95,048 paid subscribers in the past 20 years.

The weekend audit reports, which measure the subscription numbers for the flagship publication of each newspaper (Sundays for the Portland, Augusta and Waterville newspapers; Saturday for the Bangor Daily News), tell of even deeper cuts. Collectively, the four newspapers have lost 132,551 subscribers in the last 20 years – 54 percent of their total weekend audience.

The state’s largest newspaper, owned by Brower, has suffered the deepest cuts, in terms of total audience. Since 1997, the Maine Sunday Telegram has shed 70,000 readers – 56 percent of its audience. According to its 2017 audit report, the Sunday Telegram paid subscriber base stands at 54,506. Twenty years ago, it was 124,589.

Two decades of deep audience cuts – and corresponding drops in advertising revenue as businesses spread their ad dollars to places with greater reach – have unquestionably altered the business model for Maine’s newspaper publishers and cannot be overlooked. As have the corresponding drops in advertising revenue.

But many people in Maine and around the country see the momentum around Reade Brower’s local ownership as a positive for an industry so desperate for something good. Can Brower, and the rest of Maine’s publishers, find some success before Maine’s newspaper industry fades into history?

“The reality, to me, is to recognize that there is no silver bullet to fixing this,” said Brower, who bought the Press Herald/Telegram, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel in 2015, the Lewiston Sun Journal in 2017, and the Times Record and Biddeford Journal Tribune in April. “It is about hard work and adding one reader at a time back to either print or paying for digital access.”

An industry on the brink

The newspaper landscape is bleak, to be sure, pretty much everywhere.

“There’s been no growth overall in the industry since 2007. It’s been down revenues year over year,” said Ken Doctor, a former Knight Ridder editor and digital content expert who runs a company called Newsonomics. His columns, which focus on the transformation of media in this digital age, appear regularly in Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab and elsewhere.

The situation for Maine’s newspapers is far from sunny, but it seems to pale in comparison to what’s going on elsewhere in the United States, where so many papers have folded or devolved into barely recognizable, shortened versions of what they once were, said Kelly McBride, a former newspaper reporter and vice president at The Poynter Institute for Media Studies in St. Petersburg, Fla.

For one thing, Maine papers aren’t owned by the likes of Digital First Media, which is wreaking havoc at many of its nearly 100 newspapers around the country, and is controlled by hedge fund Alden Global Capital. Since April, for example:

- Fed up with round after round of cutbacks, employees and union officials at The Denver Post are publicly protesting the way Digital First is running things. Denver’s mayor and Colorado’s governor are chiming in. Post editorial page editor Chuck Plunkett wrote about the paper’s struggles in April: “If Alden isn’t willing to do good journalism here, it should sell The Post to owners who will.” Owners refused to publish a subsequent editorial, Plunkett resigned, and the union expressed outrage at “unconscionable censorship” on top of employees overworking in a demoralizing environment.

- Doctor revealed last month in Nieman Journalism Lab that Digital First also has been demanding 17 percent profit margins while slashing staff.

“How much profit is enough?” asked Michael Socolow, an associate journalism professor at the University of Maine and a Maine Press Association board member. He said the demands to pay hedge-fund owners makes it impossible for many papers “to operate as they should” and added that “I don’t see Reade Brower behaving in the same way as these hedge funds.”

Also impossible is covering “basic government units” when most newspapers have had massive losses, said Doctor, noting that 24,000 journalists work at newspapers nationwide now compared to 56,990 in 1990.

GateHouse Media, another huge chain with more than 100 dailies and more than 600 other community publications (including the York County Coast Star and York Weekly), also has cut staffs, reduced coverage, and is beholden, said Dan Kennedy, a Northeastern journalism professor and author of a recent book, “The Return of the Moguls: How Jeff Bezos and John Henry Are Remaking Newspapers for the Twenty-first Century.”

“(GateHouse’s) money goes straight to a hedge fund in New York. Compared to that, a relatively benign chain like Reade Brower has put together is far more preferable,” Kennedy said. “If he has locked down Maine in a way that keeps chains like GateHouse and Digital First out, and if he’s taking his responsibilities as owner seriously – and from what I’ve been able to tell, he is – this situation is good for Maine.”

Kennedy, Doctor, McBride and other media experts say newspaper quality is suffering in most cities because longtime reporters and editors with great community knowledge are the ones being bought out and laid off; overworked editors in reduced newsrooms aren’t catching mistakes and typos, making readers frustrated enough to cancel subscriptions; and content sharing has become a substitute for local content.

“In many cases, papers purport to be local but there’s no connection to the community because staffs have been cut so severely,” Doctor said. “Hopefully, Brower will be smarter than that and recognize that some stories can be run statewide but localized. Maine readers will be OK if management of these papers keeps in mind the very American value that a diversity of voices, not a single voice, is an absolute good.”

Brower’s ownership sparks hope, scrutiny

Considering the situation elsewhere, analysts contend that Maine actually is in an enviable position in having a single person with Brower’s sensibilities – and not “vulture capitalists,” not corporate chains, not hedge funds – owning the majority of its papers. (And, yes it’s unique – no other state comes close to having a single person owning Brower’s percentage of papers).

Brower seems genuinely interested in journalism and in his properties, and that’s sadly more of an exception rather than a prerequisite for newspaper ownership these days, said McBride.

“This guy (Brower) doesn’t seem to be demanding unreasonable profits and is trying to keep things going,” she said. “There are certain vulnerabilities, but in terms of the threats I see to journalism over the whole entire country, they’re things that can be dealt with. It’s not a guy cutting staff to the bone, stopping contributions to the pension plan, not covering issues that should be covered, and making the place a shell of what it used to be, trying to squeeze every last cent out before bankruptcy.

“It sounds to me like Maine is lucky,” McBride asserted. “It’s not a news desert like much of the rest of the country, with papers closing up left and right.”

Doctor – who advises media owners all over the world on creating new sustainable business models and revenue streams – agrees.

“As I understand it, Brower has said it’ll all be locally run and edited and he isn’t demanding big profits,” he said. “If this is the case, places like the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting need to keep an eye on him, but clearly, you’ll have a much better result in Maine than 90 percent of the country if he does that and keeps staffing at a fair level.”

Brower, 61, has repeatedly said he is committed to being hands off the newsroom and advertising operations for these papers because he has strong management teams he can trust and rely on.

“As long as I have Lisa (DeSisto) as chief, (executive editor) Cliff (Schechtman) in Portland, and the rest of my management team, who understand the integrity of newspapers, I have very little interest in the editorial side and don’t have a vested interest in what the voice is,” he said. “I want it to be balanced, fair and honest. I stand as more moderate politically and lean to the left socially and to the right financially, but the papers don’t have to follow my philosophies. They just shouldn’t be on extreme sides.”

But at a time when running newspapers is challenging to say the least, veteran Maine journalist Al Diamon doesn’t appreciate Brower’s hands-off approach, going so far as to say it shows “a lack of caring.”

“He’s not figuring it all out. He’s left it to managers to figure out,” said Diamon, whose “Politics and Other Mistakes” column appears in several Brower-owned publications. “And maybe Lisa DeSisto is planning to initiate massive changes, but I’m not optimistic that what she’s going to do is in the best interest of readers.”

Diamon isn’t impressed with what he’s witnessed thus far. “He’s (Brower) got multiple weeklies in the same market, and all the content sharing that’s happening between his dailies means essentially that there’s one newspaper. And he’s not really thought about a business plan, and that’s not a sensible way to run a business.”

Further, Diamon said, having all reporters being paid by the same owner has eliminated competition and thus impacted quality.

“In the ’70s and ’80s at the Statehouse, there were a dozen reporters covering a single story. You knew you had competition so you had to work hard with constant pressure to do better. It made us better, and I don’t think so little competition is a good thing. It’s dangerous, and it makes the news homogenized when there’s less of a sense that anyone will scoop you.”

Chris Busby, editor and publisher of The Bollard magazine in Portland, which is printed by Brower-owned Alliance Press in Brunswick, wrote in April that “there’s no way it makes ‘common sense’ for Brower to operate multiple community-news publications in the same micro-markets, like South Portland … or Bath/Brunswick (where Brower’s now got The Forecaster’s Mid-Coast edition, the free weekly Coastal Journal, and the Times Record).”

He predicted trouble, too.

“The shuttering of several of these papers and/or significant layoffs across all departments are almost certain to happen in the coming months.”

Brower concedes that some trimming of jobs and consolidating has been and will be necessary, but “I have never believed you can cut your way to prosperity. I think the way to prosperity is through keeping your product strong. If you’re running a coffee place, and you decide to make weaker coffee because it’s cheaper, you’re going to lose people. I think it’s better to ask customers to pay 10 cents more and get a good cup of coffee.”

When cuts are required, Brower said he’ll opt for “a much kinder way to do it” when possible, offering early retirement first. Two weeks ago, for example, early-retirement offers went out to 24 MaineToday Media employees, with a target number of 10 cuts.

And Brower is more than fine with there being more than one paper in any given market.

In Rockland, for example, he said his original paper, the alternative Free Press, and the other weekly, the Courier-Gazette, meet different community needs and have been successfully operating independently, just as they always have, since he’s owned both for the past six years.

“The Free Press is free and has no interest in covering fires and accidents and obituaries and sports, and the Courier is the paper of record and doesn’t want to be a free paper. Both are well respected in their communities and they’re both sustainable.”

And to criticism and fear about his potential for success or failure, Brower said, “If people want to look under rocks for the bogeyman, so be it. We need people like that. That’s the beauty of living in America. We are taught to question things and look at both sides. People have a right to do that and it sparks discussion. But there are ‘yes’ people and ‘no’ people, and I’d rather be optimistic.”

The numbers tell a tough story

Being optimistic is a challenge if you spend much time looking at the circulation performance for Maine’s daily newspapers.

Since 1997, cuts in daily circulation have been deepest at Maine’s two largest newspapers, the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, founded in 1862, and the Bangor Daily News, in business since 1889.

Twenty years ago, the Press Herald had a daily print circulation audience of 74,502 and a Sunday audited audience of 124,589. The paper’s 2017 audit report from September lists the PPH daily circulation at 38,560 – that’s a drop of 35,942 readers (48 percent) in 20 years. The circulation of the Sunday Telegram, the state’s longtime flagship newspaper, has dropped 56 percent in that timeframe, down to 54,506 – a loss of more than 70,000 readers.

Maine’s second largest newspaper, the Bangor Daily News has seen even deeper cuts – more than 60 percent fewer readers now compared to 1997. The BDN had a weekday print circulation audience of 70,280 two decades ago, and weekend circulation of 83,908. A fourth-quarter audit report from last fall shows the Bangor Daily News weekday print circulation at 25,837 (a drop of 44,443 in 20 years) and its weekend print circulation audience at 31,932 (down 51,976 readers).

“Is print media dying? That’s too simple a way of asking. I think people are shifting away from print in some cases, but print will persist for a very long time because people still want newspapers,” said Bangor Daily News President Todd Benoit. “Is it dying? No. Is it shrinking? Yes. And what will change is the reach of print, how frequently papers are delivered, what shape it takes.”

The numbers for the past 10 years in Maine are even more sobering.

Since 2007, the four audited newspapers all reported losses of at least 34 percent (the Morning Sentinel in Waterville) and as much as 55 percent (the Bangor Daily News) for their weekday print circulation totals, and at least 27 percent (Morning Sentinel) and as much as 51 percent (the BDN) for weekend totals.

The Morning Sentinel, established in 1904, has lost the least amount of audience among these four papers, shedding 8,453 daily readers (39 percent) and 4,929 weekend readers (27 percent) since 1997.

By comparison, the Press Herald/Telegram has lost 35,942 daily readers (49 percent) and 70,083 weekend readers (56.2 percent) in the same timeframe.

Major declines in print circulation are happening everywhere. In 1997, total circulation for all U.S. daily newspapers was 56.7 million. At the end of 2016, it was 34.6 million, a drop of 22.1 million (39 percent).

To understand how any papers have managed to stay afloat even though readers have left in droves, you have to look at more numbers.

“One way papers are surviving has been to double prices over that same span. I bet they’ve (Maine papers) doubled their prices in 10 years, and if so, they’ve come up with the same amount of revenues so that it’s sustainable,” Doctor said. “The question becomes, though, what are the limits on how much you can price up? Most publishers are finding that they are hitting a wall in terms of pricing.”

The Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News have, indeed, more than doubled their newsstand (or single-copy) prices in 10 years.

The newsstand price of the Portland Press Herald (now $1.80) has gone up by 140 percent since 2007, when it cost 75 cents. The current Telegram newsstand price ($2.80) is 60 percent higher than 10 years ago ($1.75). Likewise, the BDN newstand price is 108 percent higher than a decade ago (60 cents to $1.25); its Saturday edition (it doesn’t publish Sundays) price has increased by a third, from $1.50 to $2 over 10 years.

Both papers have had less luck with home subscription rates as they carefully juggle defecting subscribers and the need to raise prices.

The average home delivery rate for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram is $6.50 a week (for all seven days, plus the electronic edition and website access). That’s up by $2.43 over the 2007 price of $4.07 a week.

The BDN has raised prices at a slower rate, from $3.95 a week for home delivery in 2007 to $5.59 a week now (for all six days, plus website access).

What’s stemming the tide?

Despite the rather dismal state of the newspaper industry, and the stark circulation numbers, when asked about the general health of Brower’s newspaper properties, CEO DeSisto said, “all of our properties can stand on their own.”

How is this possible?

It’s possible, Doctor explained, because of the world we’re living in, where most newspapers now strive to stop revenue slides and aim for the “unsexy digit:” zero, as he called it in a 2013 still-relevant Nieman Lab column.

“Zero is good,” he said. “The higher performers are employing strategies focused on beefing up digital subscriptions, and emphasizing new revenue streams. And if you execute those well, you get to flat – which is pretty much the best you can do in these times. If you can do that and operate smartly, it can work.”

“Flat is the new up,” said Brower, agreeing that flat is a realistic expectation in current conditions. “Our revenue is flat because of raising prices and the other measures we’re taking.”

“Digital is the place of growth, as well as diversifying,” he said, echoing what Doctor and other analysts are recommending. “There’s no way to paint a rosy picture, but it’s not a completely dark picture. There are lots of things that we can do to make the glass half full.”

DeSisto, CEO of all Brower media properties except The Free Press and Courier Publications, said her team is aggressively marketing paid digital subscriptions across Brower’s properties, and it’s paying off, with digital-only subscriptions pacing ahead of projections.

“We are seeing continued growth in digital subscriptions – a monthly average of 43 percent (year-over-year growth) for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel so far this year,” reported Stefanie Manning, group vice president of Consumer Marketing for MaineToday Media and Sun Media Group.

Digital-only subscriptions currently account for only 16 percent of circulation numbers for Brower’s papers, she said.

“The exciting part of digital is that you can go after a wider audience,” added Brower. “You can hit the snowbirds in winter and give them online access to their paper. We have to figure out ways to take advantage of this kind of thing. There are a lot of opportunities in the digital world.”

According to DeSisto, things have been looking up this year.

“Many of our papers are pacing ahead of last year in terms of advertising and circulation revenue,” she said. “We are focused on revenue growth with everything from sponsored content to our event series.”

At the Bangor Daily News – Maine’s only daily that Brower does not own – Benoit said new revenue-generating ideas always are top of mind, by necessity.

“Everyone in newspapers who is in management spends a lot of his or her time thinking about new sources of revenue and how to make existing sources work better,” said Benoit, noting that in the declining circulation equation, corresponding savings on trucking, paper, ink and other costs help offset some of the revenue losses. “Obviously, things are a lot different than they were 20 years ago, but this isn’t a new problem. We’ve been living in this space for a long time. We’ve been working on this for 10 years.”

The BDN is trying many of the same steps as other papers. It was the last major paper in Maine to add paid digital subscriptions with a website paywall, which it did just last November for desktop and laptop users. Benoit expects a mobile version to be rolled out in next couple of months.

The paper hadn’t felt a need to charge for website access until recently because it expanded its distribution and coverage six or seven years ago, Benoit explained. “It was doing fairly well, but when there was a leveling off of traffic, we decided to do this.”

Like many others around the country, his paper has recently created a marketing agency to counteract ongoing circulation losses, too.

Innovation for Maine’s Ellsworth American and Mount Desert Islander has included establishing a website production and maintenance service within the papers about eight years ago, said Alan Baker, publisher of both papers. Printing other small papers in the region and jobs for corporate clients has generated revenue in recent years as well.

“We’re living in a time when we’re all reinventing ourselves to do the job of reporting local news,” said Baker, 88, who started his newspaper career in 1960 with The Philadelphia Inquirer.

At that time, when “we started every Sunday with 80 full pages of advertising,” he couldn’t envision a world where retail advertising would wind up so devastated because of people getting their news from so many – and often unreliable – sources beyond newspapers.

DeSisto said her papers are always looking for efficiencies. A key benefit to common ownership of six dailies and many other publications, she said, is providing centralized services, which cuts costs and ultimately will better serve readers.

“These services include digital development and digital ad serving. It would be very difficult for some of the smaller properties to support those services on their own. Once we are on the same systems, we’ll be able to have a common customer-service experience and optimize our home delivery routes. Before we can get the full benefit of cross-selling and make it easy for advertisers to buy across properties, we need all properties to work from the same advertising platform. This work is underway.

“This stuff doesn’t happen overnight. It’s all in process, but the end state is very promising,” said DeSisto, who also is encouraged by the status of management’s relationship these days with Local 128, the News Guild of Maine, which represents workers in marketing, circulation, advertising and the newsrooms of the Portland and Waterville dailies.

“Sometimes people say, ‘Oh, you have a unionized workforce.’ But that’s not an impediment to our success and work here,” she said.

Guild President Jim Patrick, social media editor for the Press Herald, said the relationship “is better than it’s been in many years,” particularly after the chaos of the Richard Connor regime (CEO from 2009 to 2011 accused of misappropriating more than $500,000) and the financially challenged Seattle Times, which sold the papers to Connor’s consortium in 2009 after 11 years of ownership.

“We feel these people (DeSisto and Brower) want what’s best for the employees and they’re the right people for the job,” Patrick said. “It’s definitely guarded optimism when we’re seeing cost-cutting but not filling jobs” and with buyout offers happening. “It’s not a great situation, but they’re at least keeping us in the loop, and that’s a huge difference compared to past administrations.”

Believing in the power of print

Brower calls the combination of efforts being undertaken in Maine “baby steps” that collectively sustain papers.

But for how long? And are such efforts really enough for Maine newspapers to do more than just tread water?

“We didn’t go into the year with a negative budget, and we didn’t have an expansion of profit,” he said. “We can’t go on like that forever, but you can still create synergies, and do this and do that before having to cut a lot of bodies to keep a viable product. If you’re losing 2 to 4 percent a year, can you continue to sustain losses year after year? No. Eventually it gets to a point of no return. But right now, we’re not there. It’s not jumping-off-the-ship numbers yet.”

If the forecast were so horrific, Brower said he wouldn’t be investing in new presses to handle commercial clients, which now include magazines and advertisers who left print and have returned to it. He sees potential in commercial printing – enough to have seven-year debt service attached to his most recent printing investment.

“I don’t believe print is dying. Obviously, if I didn’t think the industry would last that long I wouldn’t be investing. I believe people like reading the tactile paper,” he said. “Yes, we have to concentrate on digital, but a lot of people still want to have a printed version. If coffee were to go out of vogue, and everybody wanted to drink tea, it wouldn’t mean coffee would be discontinued. You have to give people what they want.

“And people still want to sit down and have a cup of coffee and read their paper and digest the news. Digest not ingest. You’re ingesting, flipping through your phone, and you wind up at a cat video before you know it. Newspapers are still the best place to go when you want to digest the news. And as long as we are a coffee shop, I want to serve coffee.”

Brower contends print outshines digital in some regards.

“Print is still a great way to brand a product,” he said, pointing to a simple print campaign for a restaurant in his area in The Free Press and Courier papers that highlighted a buy-one-get-one-half-off deal as an example.

“Sales were 50 percent ahead of last year, we noticed many new faces and the credit cards showed people traveling from 20 miles away to come to the tavern. Interestingly enough, we did the same offer on our website (Village Soup, which has more volume of readership than the papers) and had very light action from that – print outperformed it about 25 to 1. We got many more coupons cut out from the papers than people printing them from the website and bringing them in. So even though the audience for print was lower, they saw the ad, they cut out the ad, they acted on the ad. As long as that happens, advertisers will continue to find a place in their budget for print.”

Brower also noted that “the demographics of print readers is very strong; disposable income and an older readership is all good when it comes to spending money.”

Man without a grand plan

Brower said he is unfazed by naysayers who doubt or wonder about his ability to sustain operations and make his ownership arrangement and properties successful.

“It’s their job to speculate, but they don’t know,” he said. “I’m the closest to it who could know, and I think it’s a viable model. I believe there is a niche for mainstream media to perform a service as an information gatherer and watchdog. There should be a business model that follows that is sustainable. If you fill a niche, you will make money. That’s been the history I’ve seen over time.”

As he often does when asked about specific plans, Brower shrugs.

“I don’t have a grand plan,” he said. “I don’t have a plan for the next five minutes. I don’t have any magic bullets. You just have to go back to basics and hard work, provide good reporting and get ad sales people out there on the streets to sell.”

Doctor said many eyes will be watching Brower’s “fascinating example” play out.

“All of the negatives about Brower seem to be potential dangers,” he said. “I understand in the abstract about the risks connected to this single ownership. But it’s a risk worth taking.”

Adds Bangor Daily News owner Rick Warren, who has his paper printed via Brower’s organization, “while it may seem troubling to have so much of Maine’s print media concentrated in one entity, on balance, I would say it has not been a bad thing. That could change should he decide to sell his holdings to an out-of-state entity.”

The only big concern for Doctor has nothing to do with Brower’s approach.

“What if he gets hit by a truck? What happens then?”

Brower concedes that’s a reasonable concern that he’s working to address.

“That’s part of the puzzle I’m trying to put together,” he said. “I don’t have a succession plan right now, but I’m working on a longer-term solution. It’s not a family business that our kids will be taking over – it’s been my wife and me. So if a bus were to hit me tomorrow, hopefully I have people behind me that would work in my best interests and for my family’s best interests and the papers’ best interests.”

“It’s an important model that can work if he can sustain it,” Doctor said. “And it would be nice to see it work.”

But … does it really matter?

If owners and managers of newspapers stopped scrambling to generate new revenue, and newspapers actually did phase out, would it matter?

The consensus among analysts and others is that newspapers still matter a lot – to our democracy and society, and digital sources aren’t an adequate replacement system.

“Without newspapers, most communities would not get a regular diet of local news about the local schools and local governments. And that’s just the beginning,” said McBride of Poynter. “Television and radio newsrooms and even local online startups often approach news as a niche product for certain audiences. Daily newspapers look at news as a service to the entire community.”

At stake, said Socolow, the UMaine professor on the MPA board, is important reporting like Matthew Stone’s 2017 investigation for the Bangor Daily News into the millions that Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services used unlawfully.

That type of work “requires the support of independent editors and a publisher unafraid to reveal ineffectual and possibly illegal governmental behavior. That independence requires economic viability, and that’s why the economic issues in the media today have ramifications for effective civic governance and an informed citizenry,” Socolow said.

Losing newspapers would mean a “huge loss of accountability journalism,” Kennedy agreed. “Newspapers are also able to effect change because they are reaching a broader swath of the public than, say, a small nonprofit journalism project online, which may be ignored.”

“We’d be in trouble,” said Brower about the potential of losing newspapers. “It’d bring us closer to other countries that don’t have the First Amendment protections we have” and it would mean a loss of key things newspapers do: “most importantly serving as a watchdog, and also keeping communities connected and informed about what’s going on, and providing an open forum for discussion.

“I also think that print cuts through the clutter that all the other media has. With print, you take your time. It doesn’t disappear if you slap a fly off your wrist or get up for a cup a coffee. We’d miss that.”