Hailey Ann Goding loved anything that sparkled.

The 3-year-old also adored her pet chickens and insisted on taking them to McDonald’s for chicken nuggets. The blond-haired girl was just beginning to grow fond of owls when her short life ended.

Hailey’s mother, Hillary Goding, called 911 at 10:48 p.m. on June 4, reporting that her daughter was unresponsive and not breathing. Police later learned Goding waited 20 hours to seek help even as her daughter’s breathing grew raspy and her body became limp.

Hailey died, police said, after ingesting fentanyl. Her 28-year-old mother was arrested and charged with manslaughter. It wasn’t the first time the child had been exposed to drugs in her Old Town home. A year earlier, Hailey also needed medical care in an episode that was reported to the state’s child protective system.

It is unclear what type of investigation Department of Health and Human Services social workers conducted in the May 2020 incident or why they concluded Hailey – then 2 – was safe in her home.

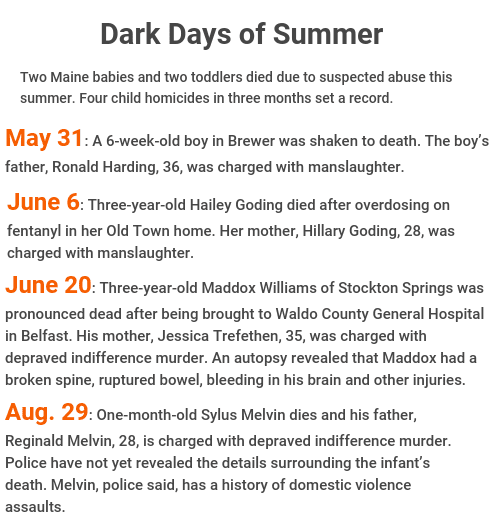

The toddler’s death is one of the four child homicides this summer that came after state child welfare workers were aware of a concern in the home.

Troubling trends

Those deaths were not anomalies.

According to a newly released DHHS report, 143 Maine children died of neglect, abuse or in accidents from 2007 through May 2021 and each was known to the state’s child protective system. In many cases, social workers had been involved with the family for several years. The report excludes the four recent homicides.

Of the 143 deaths, 35 were from co-sleeping; 34 from suicide, natural or undetermined causes; 30 were homicides; 26 were accidental; and 18 were due to SUID – sudden unexplained infant death.

“In retrospect, it seems easy to pinpoint that these fatal maltreatment cases are filled with red flags,” said Emily Douglas, a family violence expert. “Caseworkers often see red flags working with families who are neglecting or abusing their child, but they often don’t know when the case is moving into the red zone.”

RELATED: Child homicides are the tip of Maine’s ‘iceberg of abuse’

Christine Alberi, Maine’s child welfare ombudsman, echoed Douglas’ concerns. Alberi has reviewed hundreds of incidents involving child abuse and neglect, and repeatedly has cited cases that put children in danger due to inadequate child protective investigations.

“It’s been frustrating because it’s been the same thing again and again,” said Alberi. “There is a lack of prioritization on when the safety of children is at a high risk, which is at the beginning of cases and at the end of cases.”

Training often lacking for investigators

Flawed child protective investigations in Maine and throughout the country are often due to poorly trained caseworkers, said Douglas, who has researched child abuse and neglect for 20 years, and studied at Portland’s Muskie School of Public Service. After surveying 1,000 child protective social workers nationwide, Douglas found that social workers lack knowledge in fatal risk factors.

“Case workers have a lot of misconceptions about children who die in the home,” said Douglas, who now chairs the Department of Social Work & Child Advocacy at Montclair State University in New Jersey. “Many tend to think most kids die from abuse, but the majority die from neglect.”

Social workers also harbor misunderstandings about who is typically responsible for a child’s death in the home.

“Most often they think it’s the mom’s boyfriend,” Douglas said. “But the person responsible is usually the biological or birth parent of the child, and most often it’s the mom.”

Supervisory neglect tied to deaths

Neglect, particularly when it comes to supervision, is the biggest risk factor to most children, Douglas said.

“Children are neglected by being exposed to the elements, or not getting enough food or medical care,” Douglas said. “But the most lethal type of neglect is supervisory neglect.”

In cases of fatal neglect, the child’s death results in the parent’s failure to keep their children safe. Kids exposed to drugs in the home, toddlers falling out of windows, drowning in bathtubs, or young children who accidentally shoot themselves are lethal consequences of inadequate or negligent supervision, Douglas said.

Co-sleeping deaths, in which a parent accidentally smothers an infant, are also considered neglect, Douglas said, and often involve caregivers with substance use issues.

Of the 143 children who died from 2007 through 2020, co-sleeping deaths represented 25 percent of fatalities. Co-sleeping deaths dropped from six in 2019 to three in 2020, after DHHS partnered with hospitals, healthcare professionals and community agencies to educate parents about the dangers of unsafe sleep conditions.

In her research of child protective workers, Douglas found that the risks of co-sleeping and other harmful behaviors are sometimes downplayed because caseworkers say they are pressured to find “strengths” in the parents they are assessing.

“I’ve seen cases where the parent is using substances and sleeping with their baby,” Douglas said, “But the caseworker says, ‘The mom really loves her child and it makes her feel good to sleep with them, and I see that as a strength.’ ”

Regardless of whether the mother loves her child, the infant is in jeopardy, Douglas said.

“The thinking is that if a family has strengths, it must cancel out the risks,” Douglas said. “And that’s not the way it works.”

In multiple cases involving those 143 child deaths, Maine caseworkers found prior neglect, abuse, domestic violence and substance use. Though the DHHS reports cite that parents in these cases were referred to community agencies and services, it’s unclear if the caregivers cooperated and followed through with treatment.

In her 2020 report, child welfare ombudsman Alberi noted that despite DHHS’ newly implemented Structured Decision-Making tool, which determines whether neglect and abuse allegations require child welfare investigation and possible intervention, “the same basic investigation practice issues that have been repeated for many years are still occurring: not recognizing risk when the evidence is clear.”

Alberi cited several cases in which babies and children were exposed to violence in unsafe homes:

• Protective workers reunited a child who had been taken into state custody too quickly, without re-evaluating the parent and a new partner. The couple had a new baby together and the infant’s safety was not adequately assessed. The baby died from injuries sustained from one or both parents a few months after the case was closed.

•An infant who failed to gain weight and had fractured arms was placed in unsupervised visits with one parent when it was unclear which caregiver had inflicted the baby’s injuries.

• Given the parent’s history, a trial placement with an infant was started too soon. Significant issues such as the mother’s consistent involvement with domestically violent relationships, mental health issues and substance use were not addressed. The parent also refused to cooperate with DHHS.

In her role as a former assistant attorney general in the child protective division from 1990 to 2011, Lou Ann Clifford handled numerous cases involving neglected and abused children. Social workers sometimes closed cases too quickly, she said, because they were unable to gather evidence.

“They would investigate a suspected abuse or neglect from a teacher, and then they’d go to the home and either the parent refused to talk, or the child didn’t substantiate the abuse,” Clifford said. “It would drive me crazy because then the case would be closed.”

Clifford often advised caseworkers to go to court and get a preliminary child protection order to compel the parents to cooperate.

“If you’ve got concerns that appear to be valid from a medical professional or teacher, you can still request an order that requires the parents to talk,” Clifford said. “We don’t have to wait for the harm to happen.”

Clifford wonders if a court order would have saved 10-year-old Marissa Kennedy, who was beaten to death in her Stockton Springs home by her mother and stepfather in February 2018.

“Caseworkers went out to Marissa’s home a number of times but they never found that she was at risk,” Clifford said. “The stepfather always had excuses why he couldn’t talk or why they couldn’t see Marissa.”

While this summer’s four child deaths prompted investigations by state lawmakers and an outside agency, DHHS spokesperson Jackie Farwell said the department is “working to do all we can to learn from the recent child deaths and improve our approach to child welfare. The death of a child is a tragic loss – for that child’s future, their family, their community and our state.”

Need for reforms cited

State Sen. Bill Diamond (D-Windham) is not convinced that DHHS will make needed changes. He has called for reforms to the child welfare agency since the death of 5-year-old Logan Marr, who was killed by her foster mother in 2001.

“For 20 years, ever since Logan Marr’s death and now with these recent horrific deaths, they’ve been saying (they will) make improvements,” Diamond said. “But it never really changes.”

To ensure that the investigations and scrutiny continue, Diamond has planned a two-day event called “Walk a Mile in Their Shoes.” On Sept. 28 and 29, Diamond will stop in six Maine communities where children have died due to abuse or neglect in recent years.

“We will gather in each community, and hold a listening session and a rally,” Diamond said.

The first session will be held in Old Town in memory of 3-year-old Hailey Goding. Diamond will continue on to five other towns to remember Logan Marr, Kendall Chick, Marissa Kennedy, Jayden Harding and Maddox Williams.

“If we don’t continue to bring this issue before the public and bring details of how these kids died, then the bureaucracy wins, and they’ve been winning for a long time,” Diamond said. “It’s our job to remember and do everything we can to protect our children.”

Maine’s child abuse hotline is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you suspect child abuse or neglect, call 800-452-1999. Calls may be made anonymously. Click here for more information on the reporting process.