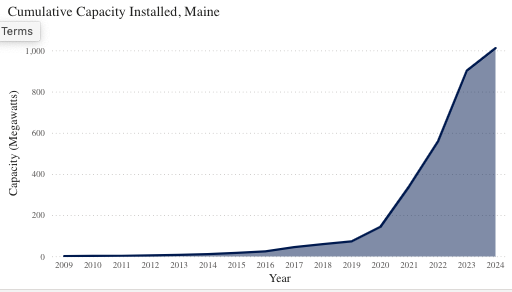

Farmington and Sanford lead the state in solar development, according to the Governor’s Energy Office, a result of their proximity to high-voltage transmission lines, municipal advocacy and the relative availability of large undeveloped blocks of land.

Farmington has the most solar installed in the state with 94.2 megawatts, followed by Sanford, with 62.6.

Farmington’s dominance is largely due to a 76.5 megawatt array on a farm along the Sandy River — reported to be the largest array in New England when it came online several years ago. The project was a joint venture supported by Bowdoin College in Brunswick and partners in Massachusetts.

The panels were erected on roughly 300 acres of farmland and woodland after dairy farmer Bussie York lost a contract with Horizon Organic in 2018 and was forced to downsize his herd, according to reporting by Maine Public.

In Sanford, the prevalence of solar is partly the result of more than a decade of advocacy on the part of City Manager Steven Buck as well as the city’s sweet-spot location, said Dale Knapp, head of Walden Renewables, which has developed several projects in the area.

Sanford is near enough to multiple 145-kilovolt transmission lines that it’s relatively convenient to wheel large amounts of power onto the grid. But it’s distant enough from congested urban areas that large blocks of land (50 acres or more) are still available for development.

“Sanford is uniquely positioned,” said Knapp. “It’s kind of a balance.”

Knapp added that Sanford’s “development-friendly” business climate facilitates solar development, although that is less important. “It really is about transmission capacity and available land, then land use ordinances.”

When Buck became the Sanford town manager in 2011, the solar industry in the United States was still in its infancy. Prices for panels, which had been prohibitively high, were on a downward slide, ushered along by a federal push to bring large-scale solar costs in line with other forms of energy.

At the time, Maine had few incentives for solar development. The first community solar development was still several years away from coming online, and the state was governed by Paul LePage, who spent much of his tenure battling with advocates over net metering programs, which paid homeowners for installing panels and sending electricity back into the grid.

The project envisioned by Sanford officials seemed straightforward: 5 megawatts on a closed landfill just off Washington Street.

“That’s all we wanted to do,” said Buck. “In my mind I had hit the easy button.”

Thirteen years later, the landfill project has yet to be built.

But Sanford’s push for it helped bring about impactful changes in state and federal regulations, and ushered York County to the top of the solar heap, neck-and-neck with Kennebec County.

As of July, the two counties had 136 megawatts and 138 megawatts of installed solar capacity, respectively, according to figures from the Governor’s Energy Office.

An economic win

Maine’s net energy billing program, in which solar owners are paid for the energy they send back into the grid, has been criticized for its cost to ratepayers.

Bill Harwood, the Maine Public Advocate, has estimated the projects will cost ratepayers roughly $220 million annually for 20 years; roughly $275 per ratepayer per year.

Many of the state’s community solar projects have wound up bundled and sold to some of the world’s largest corporations and investment firms, according to reporting by The Maine Monitor.

But advocates for solar projects say they’re an economic boon to municipalities. In Farmington, the array on York’s property is expected to bring in roughly $20 million in tax revenue to the town over the course of the 30-year lease agreement, according to reporting by the Sun Journal.

Sanford’s solar projects bring in more than $1.2 million in gross tax revenue each year, according to Buck. At a current valuation of $74.6 million, said Buck, the projects — including the 50-megawatt array at the Sanford Seacoast Regional Airport, one of the largest airport arrays in the nation — bring in $1,214,000 in gross tax revenue. Buck said the city expects two more projects to come online in the next year.

“There’s a multitude of ways to get an economic benefit out of a well-designed alternative energy project,” said Buck.

Between lease payments, a maintenance and construction agreement, environmental offsets and other benefits, the airport project alone brings in an average of $16,279 per megawatt, more than $800,000 annually.

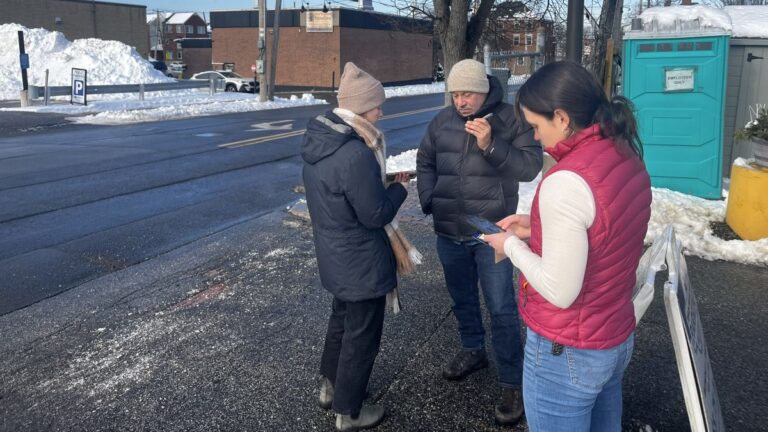

Buck and Jim Nimon, the economic development director at the time, saw the economic promise of solar more than a decade ago. They envisioned a 5-megawatt solar project on the dormant landfill, with a power purchase agreement in which Sanford would lease the land to a solar developer who would sell the electricity from panels back to the city at a fixed price.

Ambitions grew as the city looked to expand the project to 10 megawatts, with 5 on the landfill and another 5 on a Brownfield site across the road.

But building solar on old landfills is 10% to 15% more expensive than on undeveloped land – construction practices must be altered to ensure the site’s protective cap isn’t compromised, which can increase labor costs. The presence of the cap also means posts typically can’t be driven into the ground but must be stabilized with ballast or mounted on long concrete footings, an additional expense.

Landfills and brownfields, which often have remnants of industrial infrastructure and environmental hazards, may also require more in-depth review than putting posts and panels in an empty field. Landfill projects must be monitored to ensure they do not compromise the site’s integrity in the long term.

“So from a cost perspective, it didn’t pencil out,” said Buck. “It was too expensive.”

Undeterred, Buck delved into legislative advocacy, pushing for state approval for a pilot that would have allowed the proposed project to benefit from net metering, in which solar owners are paid for some of the energy they send back into the grid. The gambit failed; opponents argued that the bill was too broad and would have impacted ratepayers across the state.

In the meantime, however, Buck, Nimon and the airport manager, Allison Navia, courted a small developer who expressed interest in putting panels on the Sanford airport, a roughly 1,200-acre parcel that had 420 acres authorized for non-aviation use.

Just as the city was entering into an agreement with the company, Ranger Solar, the Federal Aviation Administration announced a temporary halt on putting panels around airports, citing concerns about glare that could impede a pilot’s vision.

Apart from the glint and glare issue, the project encountered hurdle after hurdle.

Environmental regulations meant the city and developer needed more land to accommodate the number of panels that would be necessary to make the project economically viable. The size of the proposal also required a new $8 million substation to handle the amount of power being generated.

“There was always something cropping up — real estate issues, regulatory complexities, state environmental concerns and technical hurdles,” Navia told the trade publication Airport Improvement in 2021. “The project almost died on a monthly basis for about five years.”

The project’s magnitude and innovation drew the attention of NextEra Energy, one of the largest solar investors in the U.S., leading to the project’s acquisition in 2017. The 50-megawatt project that went live in November 2020 is one of the largest airport solar projects in the country.

But Knapp said Sanford may soon reach its solar generation capacity.

“There’s a limit to the number of farms because transmission capacity is being used up. Each farm chips away at transmission capacity. The (proverbial) highway will be full. That day is not too far off,” he said.

Sanford’s pursuit of solar developments comes as other Maine communities are slowing the rush, instituting temporary pauses on development and banning larger commercial arrays. More than a dozen municipalities have paused solar development in recent years, according to reporting by News Center Maine.

The city continues to pursue more solar, however, and has partnered with Walden Renewables to develop a 5-megawatt community solar project on a remediated Brownfield site expected to be online in the coming year. It is also negotiating a tax increment financing district and a credit enhancement agreement with Walden on another 20-megawatt project to make the project more financially attractive to developers.

“It is much easier” for the city to engage with developers on projects now, said Buck. “We know how to value them … it’s just second nature for us now. We’ve conquered all of these elements.”

Correction: This story has been updated with the correct version of an image showing solar capacity in Maine.