Maine is not living up to the state law that requires regular inspections of the nearly 100 dams in the state classified as hazardous for their potential to take lives or sweep away buildings, roads and bridges.

The state has 93 such dams from Limestone to Sanford. Of those, the state classifies 24 as “high hazard potential,” meaning that mis-operation or failure could “probably cause loss of life.” The other dams are “significant hazard dams,” meaning a failure could cause property or environmental damage.

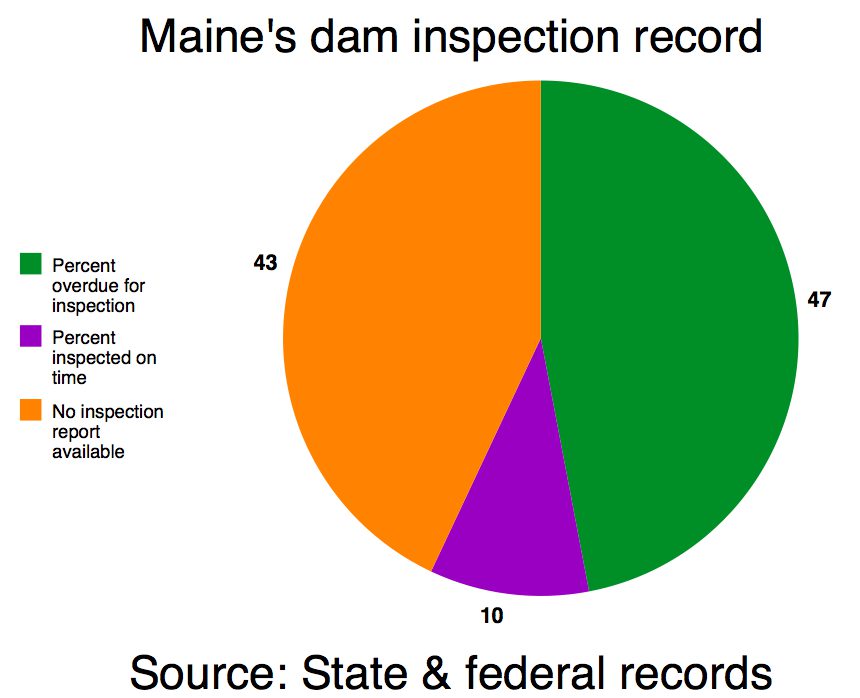

Half of the high hazard dams are two to seven years overdue for their mandated inspection by a professional engineer, according to records provided to the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting by the Maine Emergency Management Agency (MEMA).

And the state has no record of any state inspection for another 25 percent of the high hazard dams, either because they have not been inspected or because of poor record keeping.

MEMA could produce reports showing on-time inspections for only three high hazard dams.

For example, there is no record of an inspection of the dam that holds back Norway Lake, a five-mile-long lake.

An Oxford County emergency management official noted the dam is at the top of the town’s picturesque Main Street. “If that dam let go,” said Crystal Ayotte, “Main Street would be in a world of hurt.”

Although there is no report saying the Norway dam is in poor condition, there is also no state report stating it is in good condition, which is the case for 40 potentially hazardous dams across the state.

The records were requested by the Maine Center to determine if the state is abiding by the 2001 Dam Safety Law that requires regular dam inspections: every two years for the high hazard dams; every four years for the significant hazard dams.

The pattern for the 69 significant hazard dams was similar to the high hazard dams: 30 dams were an average of four years overdue for inspections, and the state could not provide inspection reports for another 33.

The Center’s findings confirmed the fears of the legislature’s leading advocate for dam safety, Sen. Stanley Gerzofsky, D-Brunswick.

“Some day something’s going to happen,” he said, “and people’s eyes are going to open up.”

ONE INSPECTOR

For most of the 20-year history of the state’s dam safety program, it has had only one engineer inspecting the state dams, from the 93 high and significant hazard dams to another 700 low hazard dams.

That inspector is Tony Fletcher, a civil engineer, who until only recently has been the sole inspector for all the state’s dams. He now has a second inspector working with him, a recent engineering graduate who Fletcher said is learning on the job.

Even so, he said, “You need about six inspectors to do the job.”

Asked how many of the state-regulated dams are past due for an inspection, he said, ‘Most of them … It just can’t be done.”

His boss until recently was Mark Belserene, director of operations at MEMA.

The dam inspection program, Belserene said, “historically has been understaffed and, I want to say, over-dammed … Given the cards we’re dealt, we’re managing it as best we could.”

The director of MEMA, Robert McAleer, said, “Do the math on the whole number of dams that have to inspected and there is only one dam inspector until very, very recently. It’s very difficult to keep up.”

(Most of the state-regulated dams are owned by private parties or local government. Maine’s hydroelectric dams are inspected by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, not the state.)

ARE THE DAMS SAFE?

The current structural condition of nearly 90 percent of both types of potentially hazardous dams cannot be determined from the state’s publicly-available records because either no record was made available or the records are out of date.

Pittsfield-based Kleinschmidt engineering consultants warned in a 2008 report by Christopher M. Vella, a structural engineer, that most of these dams are more than 50 years old and nearing the end of their design life.

“These dams,” the report stated, “all show signs of weathering and movement to various degrees” and their “continual deterioration should be cause for concern.”

That is borne out by older inspection reports that show that some of the dams without current inspection reports were and may still be in need of repair.

For example:

The Mill Street (aka Alpaca) dam in Sanford was last inspected by the state in 2003, when the inspector noted, “Of concern was the movement, settlement and material deterioration of the L(eft) toe … concrete dike wall. The spillway showed signs of concrete deterioration, minor cracking and some leakage. The sluice gate was not tested nor was the outlet pipe inspected. No deterioration of recent repairs were noted.”

That high hazard dam is six years overdue for a state inspection.

Durepo Brook in Limestone was last inspected, the record shows, in 2002, but even that inspection included no tests and no subsurface or internal inspections, only a visual inspection.

“Soil erosion, rutting and slipping of embankment” was noted and these and what the inspector called “unknown” conditions led him to state: “Leakage in the the outlet pipe into the dam embankment, especially in the pressure section, will result in the breach of the dam.”

Under extreme storm conditions, the report said, a breach would endanger 105 people downstream, 47 buildings and five bridges.

The Durepo dam is five years overdue for state inspection.

Fletcher, the state inspector, said, “There are no dams I can say are in imminent state of failure, but it’s a very hard call to make … there are dams in Maine that go back to the 1700s. Piles of stone that just stand there.”

McAleer, the MEMA director, said it’s “incumbent” on the agency to inspect the dams because “you can’t assume that a dam that was built 100 years ago is in as solid condition as it was 100 years ago.”

THE POWER OF WATER

An example of what can happen when a state-regulated dam fails occurred after heavy rains in December 1996, when the 81-year-old Highland Lake dam in Westbrook breached.

A Portland Press Herald story reported that water gushed over Duck Pond Road bridge, gouging 10-foot chunks from the land abutting the street and forced the evacuation of one nearby home.

The homeowner, Harold Macomber, 67 at the time, told the paper: “People underestimate the power of water. Look at what it’s done to the underside of this bridge in just a few hours.”

The Center asked for the most recent inspection report for the Highland Lake dam, as did the Army Corps of Engineers for its National Inventory of Dams. The state did not provide either group with a report, meaning the dam has not been inspected in some time or that the state’s records don’t show one. The Army Corps of Engineers reports that a new dam was constructed 11 years ago.

The Maine Center’s examination of state records is the first documentation of the extent of the problems with the state’s inspection program, but it is not the first time the problem has been raised.

For example, an Association of State Dam Safety Officials study showed than in 2008, Maine’s compliance with a model inspection program was 16.7 per cent, compared to the national average of 73 per cent.

MEMA has been in charge of the state’s dam safety program since 1989. Before then, inspections and safety enforcement were under the jurisdiction of the state Department of Environmental Protection, which still has the environmental responsibility.

Dana Murch, dams supervisor at DEP, said his agency gave up the inspection side without a fight because MEMA “wanted it in the worst way.”

“The program has been dysfunctional since it went over there,” he said.

“MEMA is well-intentioned but doesn’t know how to function as a regulatory agency” and prefers to “play nice” with dam owners rather than press for repairs, Murch said.

McAleer said MEMA will take a dam owner to court, but rarely has, because it recognizes that most private dam owners don’t have much money and a court case would eat up what money the owner may have rather than use that money towards a repair.

‘DO THE BEST’ THEY CAN

“Yes, I wish we had more inspectors,” McAleer said. “No, I don’t have a plan to get more inspectors. I think the fiscal realities are we have to do the best with what we have.”

For example, he said, sometimes a “cursory review” of a dam will be all MEMA can do and if no obvious problem is found, “we can go on to where we know we have a problem and focus our energies there.”

But McAleer also acknowledged not all problems can be detected with a visual inspection.

He cited a common problem of leaks developing within a dam from rotting tree roots left when trees are cut down near a dam. He said he wished dam owners would be more alert to that problem.

Asked if there were any dam that worried him, he cited two in Aroostook County, Bryant Pond and Libby Brook, both in Fort Fairfield.

‘We’re scheduled to go and take a closer look because if they failed, we’d have significant impact. Not that we think they’re in bad shape. It’s in one of those areas we want to make sure they’re in good shape.”

Libby Brook is a high hazard dam that is overdue by four years for inspection. It is less than two miles from downtown Fort Fairfield.

The state could not produce an inspection report for Bryant Pond.

SOMEONE WILL HAVE TO DIE

One of the nation’s leading experts on dam safety is Peter Nicholson, professor of civil engineering at the University of Hawaii and also a summer resident of Harpswell.

He called the dam safety programs in many states “pitiful,” but said an equally big problem is the public’s belief that because a dam “has been there a long time, it must be a good dam.”

“If a dam breaks, especially a high hazard dam,” Nicholson said, “there’s a high likelihood lives will be lost.”

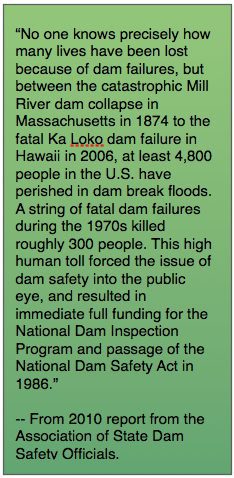

That’s what happened in his state just four years ago, when the Ka Loko dam on Kauai burst after heavy rains.

A wall of water 60 feet wide and 20 to 70 feet high killed seven people and destroyed several homes.

An investigation attributed the dam failure to a number of factors, including inadequate inspections and not enough dam inspectors to cover all the state’s older dams.

At the time, Hawaii had 1.5 inspectors; after the breach, it got three more.

“Unfortunately, “ said Nicholson, “it takes a catastrophic failure to get attention — someone has to die.”

That comment echoed one made by Belserene, the former dams supervisor in MEMA.

He recalled the attention given to to the nation’s bridges and overpasses after the collapse of a Mississippi bridge in Minnesota in 2007 that killed 13 people.

“Unfortunately,” Belserene said, “ it usually takes a lot of people to be killed before change can happen.”

PROBLEM NOT NEW: STATE WARNED BEFORE

Over the years, many warnings have been issued about the problems with the state’s dam safety program.

Nine years ago, the state’s chief dam inspector, Tony Fletcher, wrote in a report to the national Dam Safety Program:

“The Maine Dam Safety Program is critically short of resources, and the task of hydrological validation has become more and more pressing, especially in light of recent dam failures in the state.”

Since the mid-1990s, the state has had only one state dam inspector — Fletcher — to inspect the nearly 100 high and significant hazard dams and about another 700 low hazard dams. A second inspector-in-training has been on the job since last year.

Five years ago, the problem came up again, when a task force of lawmakers and public officials studied the state’s Homeland Security needs.

Their study noted that during the heavy rains in the spring of 2006, parts of Lebanon in southern Maine were evacuated due to the danger of a nearby dam bursting.

Among their findings: “ … dams in Maine need to be inspected more often and the lag in timely inspections is due to lack of staffing resources.”

The task force proposed that the legislature provide more money for the dam inspection program by establishing a fee on dam owners. That proposal was included in an emergency bill in 2007 to implement the Homeland Security Task Force’s recommendations.

But state Sen. Stan Gerzofsky, D-Brunswick, who was co-chairman of the task force and supported the proposal, said the legislature wouldn’t do it.

“It died for lack of funding – education was more important, other things were more important,” he said.

In fact, the dam fee merited little discussion in public hearings and testimony, while a proposal to establish emergency shelters that could house pets got far more attention from state officials and the public.

In 2008, the Association of Dam Safety Officials issued a report card on dam safety across the nation. Overall grade D. Maine’s grade: D+.

‘Maine current staffing levels … are inadequate,” the report stated. “Considering the age of the state’s existing dams, the demands for comprehensive and intensive safety inspections is on the rise.”

Even with the addition of a second inspector, the report stated, Maine “will still not be able to provide the necessary level of inspection …”

And in 2009, a Federal Emergency Management Agency report on dam safety found that nationally while the majority of high hazard dams “meet safety standards, their potential to cause loss of life demands stringent oversight, an often overwhelming challenge for state dam safety programs.”

It cited only three states as examples of deficient dam safety program staffing: New York, Texas and Maine.

The students in the Bates College Short Term 2011 course, “There’s More to the Story,” contributed to the research for this story: Bo Cramer, Christine Kim, Caroline O’Sullivan, Mark Lainoff, Nicole Fox, Sabina Frizell, Shachi Phene, Van Sandwick, Wylie Leabo, Jake Starke.