It’s well documented that urban and rural communities alike are suffering from our nation’s overdose crisis.

But rural regions must overcome some distinctive barriers, among them: higher rates of chronic illnesses; no, or very little, public transportation and great distances to care. A shortage of services in general.

In 2022, as part of the American Rescue Plan, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $30 million to 25 grantees to support community-based overdose-prevention programs, syringe services programs, and other harm reduction services.

Maine is the most rural state in the country. It has one of the highest drug-overdose rates in the country. It has one of the highest rates of acute hepatitis B. And it has the highest rate of hepatitis C, largely attributed to injection drug use.

Washington County, one of the state’s most rural counties, has a Walmart, in Calais, the county’s largest town (population: 3,032). But if you live in Machias, the second largest (population: 2,062), it’s an hour’s drive. You’re more likely to rely on the Family Dollar for your essentials. There’s no bus service and one taxi company.

Washington County also has the highest poverty rate in the state. It’s the nation’s easternmost county — the last stop on the line. You’ll pardon the residents of Washington County if they might feel forgotten.

Among the recipients of the SAMHSA money is MaineHealth, a not-for-profit health system, which received $1.2 million for a statewide overdose- and infection-prevention initiative.

In the summer of 2022, MaineHealth launched Project DHARMA — Distribution of Harm Reduction Access in Rural Maine Areas — a collaboration with community-based organizations, including syringe services programs.

Washington County became a beneficiary.

Strategy of reducing harm

Harm reduction embraces a set of evidence-based strategies for reducing the negative consequences of drug use to keep people alive and as healthy as possible until such time as they should be ready to seek treatment.

Among the syringe services programs participating in Project DHARMA is Maine Access Points, a statewide organization that prioritizes rural Maine.

Chasity Tuell is Maine Access Points harm reduction director for the northern regions of the state and a resident of Washington County.

This funding is “huge,” Tuell said. And, to her, it’s deeply personal. “I’ve lived in this area my whole life. The people she serves are “my community, people I see at my daughter’s school, people that I used to use [drugs] with — it’s anybody and everybody.”

In their honor

Kinna Thakarar is an infectious disease and addiction medicine physician for MaineHealth and Project DHARMA’s lead researcher. Receiving this grant, she said, was “bittersweet,” in that two people who were instrumental in the application process have since died.

Kari Morissette served as executive director of the Church of Safe Injection and Jessi Gilbert was a program administrator for Maine Access Points.

“Some of the project goals directly were their vision of what this project should be,” Thakarar said. This work, she said, is very much in their honor.

In addressing Maine’s overdose crisis, Thakarar said, “We just haven’t done enough in terms of evidence-based public health approaches.”

The services Project DHARMA is funding are just that: evidence based. Among the supplies and services syringe services programs typically provide in addition to clean syringes are saline, Band Aids, condoms, information, and referrals.

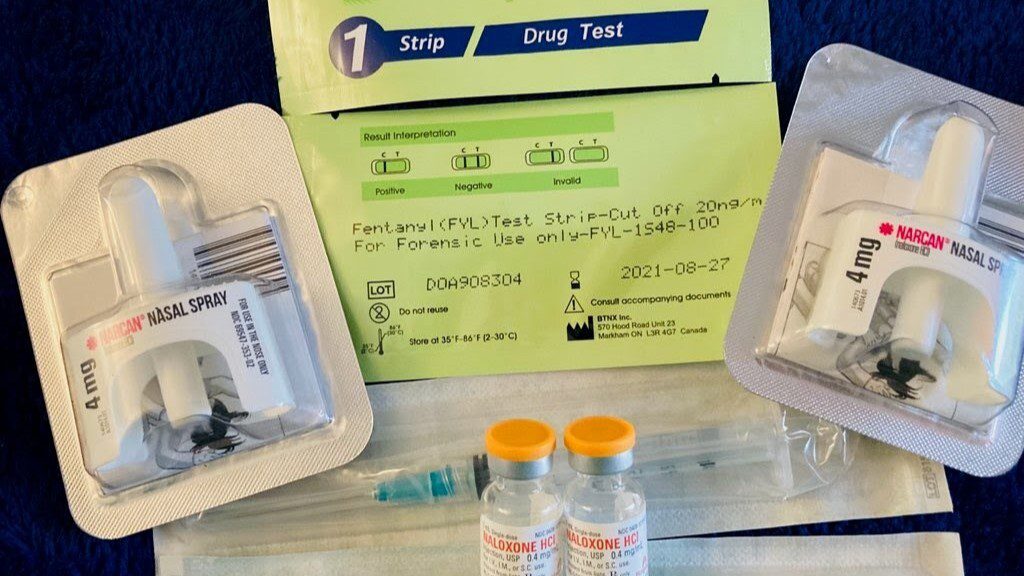

They provide naloxone, a medication that quickly reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. Studies have shown that naloxone-access laws have resulted in a 14% decrease in opioid overdose deaths nationwide.

Maine Access Points also offers fentanyl test strips, an increasingly urgent need in Maine, as elsewhere. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid estimated to be up to 50 times more potent than heroin.

“Most of what we’re seeing in Maine we’re presuming to be fentanyl at this point,” Thakarar said, “and that’s really been a game-changer.” In 2022, fentanyl was listed as the cause of death in four of five fatal overdoses in the state.

Wound care kits are another alarmingly urgent need, with the rising prevalence of xylazine, a sedative used for animal surgeries. Tuell said xylazine has been in the drug supply in Maine for several years, but “we’re definitely seeing it a lot more now.” The drug causes life-threatening wounds and sores.

The additional wound care Project DHARMA has afforded has been a godsend in a state where a hospital is often an hour or more drive away. That care is provided by outreach workers or, when necessary, by specialists, in some cases via telehealth.

The program will also promote the use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP, a therapy for preventing HIV, through primary care provider training and by raising awareness of a PrEP hotline.

And it will work to expand the capacity of syringe service providers to screen clients for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Syringe service programs are proven to reduce transmission of HIV and hepatitis C.

Harm reduction initiatives have also proven to be avenues to recovery. A study in Seattle found that participants in a syringe services program were five times more likely to enter treatment than nonparticipants.

Onsite testing

Another critical service this grant will fund is one advocates have fought hard to launch: drug testing using handheld spectrometers. Outreach workers will test drugs to determine their contents; the drugs will then be sent to Colby College for confirmation. Other academic partners are providing technical assistance.

Thakarar and Tuell underscore that with the proliferation of fentanyl, xylazine, and other emergent drugs, rapid, onsite testing is desperately needed.

But gaining permission to do so wasn’t easy. It required passing legislation “so that none of us would get arrested in doing this evidence-based public health work,” Thakarar said.

The passage of L.D. 1745, signed into law this summer, allows select individuals to possess “nominal amounts” of illicit or controlled substances for the purposes of drug testing.

“In Maine right now,” Tuell said, “really the only information that people get about what any of the drugs are is from the police and the medical examiner’s office after someone dies.”

‘Where I belong’

People in recovery often decide they must leave, at least for a time, the environment in which they used drugs.

Tuell charted a different path. Once having gained a sense of the contours of her recovery, “I felt like I was where I belong,” she said. “I couldn’t imagine not doing this work.”

Project DHARMA aims to provide services to more than 6,500 clients over three years and to link even more to health care and support services.

It’s also very much about “reducing stigma and increasing knowledge about harm reduction,” Thakarar said.

“We’re partnering with the University of New England to do harm reduction trainings for students — and not just medical students, but dental students, physical therapy students,” to provide better-informed care.

Tuell said that now when she visits her own suboxone provider, the doctor solicits practical information from her to then pass along to other patients.

“It’s really had this great ripple effect,” Tuell said.

“I think, honestly, what I’m most proud of is just the collaboration between a health system and syringe service programs,” Thakarar said. “I think it’s really helped to break down a lot of the barriers.”

In the remotest of regions, those barriers are compounded. Overcoming them can be transformational.

“Harm reduction is lifesaving,” Tuell attests. “Everybody deserves access to the care they need, plain and simple.”