They are fathers in name only, these men in prison-issued blue work shirts packed into a small room where their bulk and hulk makes three feel like a crowd. They are sitting on stacking chairs set around a folding table, admitting that they barely know their children, weren’t there when they were born, failed to support them after they were born.

“When I was doing drugs, my son needed shoes,” said Mack Wolfe II, a sturdy 32-year-old with a trim goatee and a broad smile. “To be honest with you, I didn’t help. My pills cost sixty dollars. I could not afford support, but I could support my drugs.”

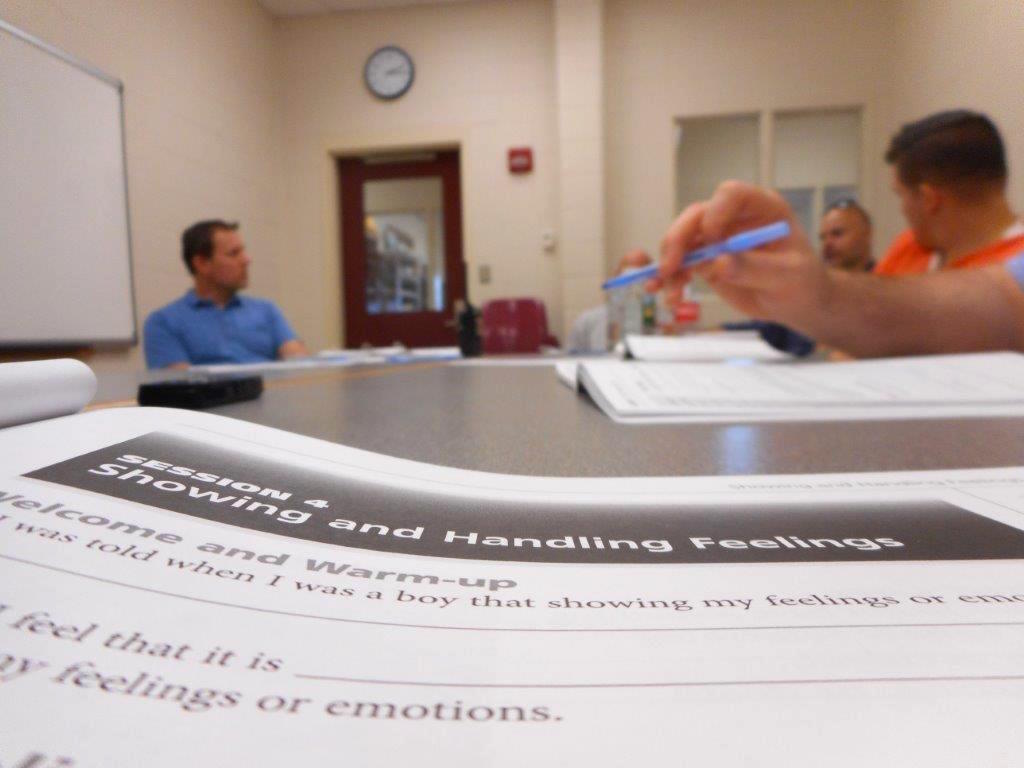

Wolfe and a handful of other inmates at the Maine State Prison in Warren have voluntarily signed up for a program called “Stepping Up: A Call to Courageous Manhood.” Attendance in the program is voluntary. It is led by the prison chaplain, who gets the men to talk about their past, their relationships, their children. Tentatively and then more fluidly, they open up about their feelings, their regrets and their hopes for the future.

These men — call them childless fathers — are the oftentimes neglected part of the story about the crisis of single parents in poverty. More than 80 percent of the children of single parents are raised by their mothers, so most of the attention is on those women. But the lack of a father in these children’s lives does a great deal of damage, say experts.

“A recent review of 45 studies … concluded that … a father’s absence increases antisocial behavior, such as aggression, rule breaking, delinquency, and illegal drug use,” writes Sara McLanahan, a Princeton University specialist on single-parent families, and Christopher Jencks, a Harvard Kennedy School professor of social policy.

These absentee fathers are usually hard to track down because they often owe child support, are avoiding the mother of their children and, if you do find them, they don’t want to talk. The men’s group at the prison offered the rare opportunity to hear these men’s stories on the record, stories some were willing to tell because they believe they are, finally, planning to do right by their children.

Wolfe, who was sentenced in 2015 to the Maine State Prison for unlawful possession of scheduled drugs, has two children: a son who’s ten and a daughter who is two. He was married to the mother of his son for five years, although “three of those years I spent in prison.”

From that point, said Wolfe, his life was “a rocky road, living for myself, being selfish, got into drug life.” And that meant, he said, that he was a “deadbeat dad” to his son — and a heroin addict.

He has lived in a world of sorry. He’s sorry for having been a drug addict, for selling drugs, for neglecting his kids. He freely admits that there was a time his addiction mattered more to him than his son. And he hopes like hell that that the things he has been able to do in prison — including getting sober and getting a high school equivalency diploma — will help him make good on the “game plan” he’s working on for the time when he’s released this month: to be a real father to his children and become a substance abuse counselor.

‘No intent’ to raise their kids

Wolfe is part of a pattern of parenthood in Maine that reflects what is happening nationally, where the number and percentage of families headed by single mothers has been growing since the 1980s, while most fathers don’t provide agreed-upon financial support for those families.

Between 2003 and 2013, according the U.S. Census, the percentage of mothers receiving the full amount of child support from fathers stayed steady, at about 45 percent.

Renee Whitley, executive director of the Franklin County Children’s Task Force, the county’s child abuse prevention agency based in Farmington, said her region is home to a lot of those families, where fathers are barely present in the lives of their children.

“Having children without intent to raise them is detrimental to our communities. We’re bringing more and more children into the world that are going to struggle and face adversity,” said Whitley.

Wolfe fit that pattern.

“I was in and out of his life,” said Wolfe about his son.

“During a period of sobriety, I met my daughter’s mother… We were together for two years, had a child together,” he said. “When my child was five months old, I had a few relapses. We were living together, but she just couldn’t handle it, threw me out of the house.”

Wolfe ended up being arrested and charged with a variety of drug-related offenses, as well as endangering the welfare of a child. While in prison, he found his way to a small, brightly lit classroom where he and several other men are led by Prison Chaplain Kevan Fortier in the Christian-based program to, as Fortier put it, “be fathers who mentor and lead their children (and) have a vision of something beyond themselves for the generations to come.”

It’s in that classroom that Fortier and two volunteers from a prison ministry group work with Wolfe and other prisoners on taking responsibility for the things they have done in their lives — including fathering children without being fathers to them.

Wolfe said that being in prison, and in this class, has helped him prepare for the responsibilities of fatherhood.

“By coming here, I got my thoughts gathered and get a game plan going. Who am I really, where do I want to be, do I really want to be that heroin addict?”

With earnings from his prison job, Wolfe said, “I’m paying child support now, I feel I do help.”

As the percentage and number of single parents has grown across the country, only 17 percent of single parents raising their children in 2014 were men, according to the U.S. Census.

The remaining 83 percent of the families are headed by mothers. And often the children’s fathers, who are living somewhere else — sometimes, like Wolfe, in prison — or with another women and her children, just aren’t involved in their children’s lives.

Just ask Debby Willis, who works in Maine’s Office of the Attorney General as the head of a team enforcing child support obligations. At any given time, said Willis, there are approximately 52,000 cases in her office’s system, representing the needs of an “astronomical” number of children and, it turns out, their mothers, said Willis.

“Ninety percent of those cases are moms,” said Willis.

She shakes her head when she’s asked about these fathers. She’s seeing a lot of them.

“This 18- to 40-year-old age category that are not married,” said Willis. “They’re in these relationships and not supporting their own children. They may be supporting the children of the new girlfriend or new wife, not supporting their own children, go from relationship to relationship to relationship.”

“We now spend a lot of time and resources trying to obligate parents who don’t have a relationship with the other parent, don’t have a relationship with the child, they don’t have an incentive to pay support.”

And those cases are made much more difficult by the new norm in Maine, which is a sizeable percentage of mothers and fathers having children with multiple different partners to whom they’re not married.

“The mom with the three children,” said Willis. “What if they’re from three different fathers, those three different fathers have other children. When you’re on your third mother and your third child-support obligation, you don’t have the money unless you’re Bill Gates.”

Tyler John Crawford, like fellow inmate Wolfe, said he, too, was one of those deadbeat dads. He was sentenced in 2014 to three years at the Maine State Prison for theft of services.

Before he had his son, Crawford said, he didn’t have a high school diploma. But that didn’t matter to him.

“I was making really good money at a young age, doing construction. Nobody could tell me nothing,” he said.

“When my child’s mother told me she was pregnant, everything was going to be okay. I increasingly saw her get more and more mature, each day.”

Despite his confidence, he didn’t get more mature.

Crawford, 22, who has a huge tattoo of winged revolvers on his right arm and “COUNTRY BOY” tattooed on his left, leans intently across the table where he’s sitting.

“It was all about me, hanging around with my friends, putting this façade on when really, I was an immensely broken person and running headfirst towards destruction,” he said.

Crawford wasn’t there when his son, who is now almost three years old, was born — he was in county jail. Like Wolfe, his later time in prison helped him get his priorities straight, he said, including wanting to be a real father to his son.

“I met my son in a visit room” at the prison, he said. “This coming Sunday will be the ninth time he’s come in. It’s the greatest experience of my life so far.”

Both Crawford and Wolfe say they want to be active in their children’s lives once they get out of prison. They’ve both finished high school while in prison, and they’re planning on further education when they get out.

If Crawford and Wolfe make good on their commitments, chances are they will help their children succeed in life. But for the many children being raised in Maine without the attention and support of their fathers, there’s potential trouble ahead.

Princeton University’s Sara McLanahan concluded in a study that “children who live with single mothers receive less financial and emotional support from their biological fathers … and their family lives are less stable and more stressful. As a consequence, they have lower educational attainment, poorer mental health, and more family instability when they grow up.”

Crawford doesn’t need an advanced degree to know how bad it is when you don’t have a father at home.

“I didn’t meet my father until I was about 14,” said Crawford. “He wasn’t around when I was growing up. My dad’s only 15 years older than me — he was only 15 when I was born. I can’t be resentful for him leaving, because he was a kid and he wasn’t ready for that responsibility.”

Chaplain Kevan Fortier said to Crawford, “That must’ve been really difficult for you growing up.”

“It drove me away from who I should have been until today,” said Crawford. “I grew up dishonestly and slyly.”

That dishonesty and slyness led to irresponsibility when he became a father.

“It seems like always the woman’s the one who breaks her back to take care of the child” these days, said Crawford, referring to single mothers. “I’m supposed to provide for my family, where am I? She’s going to school and working two jobs.”

Single mothers, said Crawford, “they accept that these guys are ‘deadbeat dads’ and they’re not here.”

He wants to change that pattern when he gets out of prison. He points to the book that’s part of the class curriculum.

“In the book it states clearly that men, boys, adolescent boys need other men to show them how to grow and progress,” Crawford said. “I think living the example is huge:, when your son sees you get up every morning and going to work, treat mom with respect, make breakfast.

“This coming to prison is the reason why I’m going to be the dad to my son that he deserves. That’s the truth — this isn’t a negative experience to me.”

Reporting for this story was supported by grants from the Samuel L. Cohen, Hudson and Maine Health Access foundations. Demographic analysis was provided by Andrew Schaefer, Vulnerable Families Research Scientist, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

This is part four of a five-part series. To read more about what went into the reporting of this story, click here.