The number one issue on voters’ minds this year is jobs.

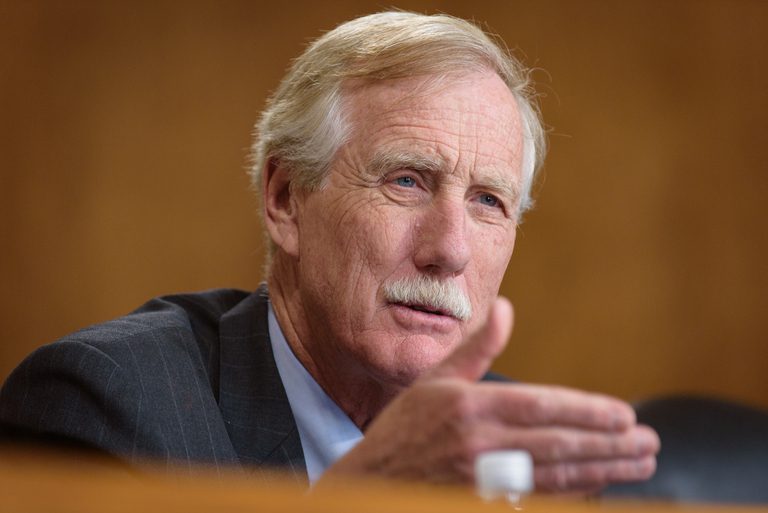

Angus King, the leading candidate in the U.S. Senate race, claims as governor he helped create jobs in Maine with some of his policies, including a program called BETR.

BETR stands for Business Equipment Tax Reimbursement. Until King became governor, businesses had to pay property taxes on equipment they purchased, from paper-making machines to computers.

In 1995, then-Gov. King persuaded the legislature that if the state gave the taxes back to the businesses, businesses would expand and create jobs for Mainers.

Under the headline “Jobs” on his campaign web site, King states that he “Nullified the property tax on machinery and equipment through the Business Equipment Tax Reimbursement Program which led directly to over one billion dollars of new capital investment in Maine.”

But an investigation of the program shows King is casting the program in a way that ignores the cost to taxpayers and the conclusions of a state audit and other studies that throw cold water on its effectiveness.

King discounts those critiques, insisting that BETR “is a good news story” that should not be seen as a tax break, but as a “common sense” correction of a tax that never should have existed in the first place.

The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting has found that:

• The Maine Revenue Service classifies BETR as “revenue foregone,” meaning it is a tax break funded by the General Fund. The lost revenue in recent years has been $55-60 million per year. That loss is made up by Maine taxpayers – to the tune of about $50-60 for every Maine adult.

The total cost of the program from inception in 1995 to 2015, the latest calculation available, will be $915 million, and it will continue to grow after that unless the law is repealed.

• Businesses do not have to prove or even claim they need the tax break in order to buy new equipment. Many well-capitalized international corporations receive checks from the state each year in the million-dollar range.

For example, in 2010 the state wrote BETR checks totaling $12.2 million to 44 Fortune 500 companies, according to a Center analysis of Maine Revenue Services records.

WalMart, No. 1 on the Fortune 500, was reimbursed $1 million in property taxes; General Electric, No. 6, was reimbursed $899,000; and General Dynamics, No. 86, got $3.3 million back for taxes at Bath Iron Works and its armaments plant in Saco.

Local businesses — large and small – also benefit from BETR. In a single year, LL Bean received a $1.2 million reimbursement and Oakhurst Dairy, $178,000. On the other end of the scale, Danny Plourde Trucking in Fort Kent was reimbursed $1,076 and Freeport Café, $706.

Most of these companies receive reimbursements year after year for the life of the equipment, for although the percentage decreases with time, it is never lower than 50 per cent, according to Maine Revenue Services.

• The annual cost of the program is no small change when compared to the overall state budget: It’s approximately the same size as the annual budget for the Department of Public Safety, which includes the state police, state fire marshal, code enforcement, state crime lab and other services.

• King’s program is considered “high risk” by the state’s independent audit agency because it ranked poorly in eight of 13 factors, including the potential for undetected fraud or mismanagement.

• A national organization called Good Jobs First, which studies business subsidies, gave the BETR program a “zero” rating because, among other things, businesses don’t have to create or retain even one job to qualify for the tax break.

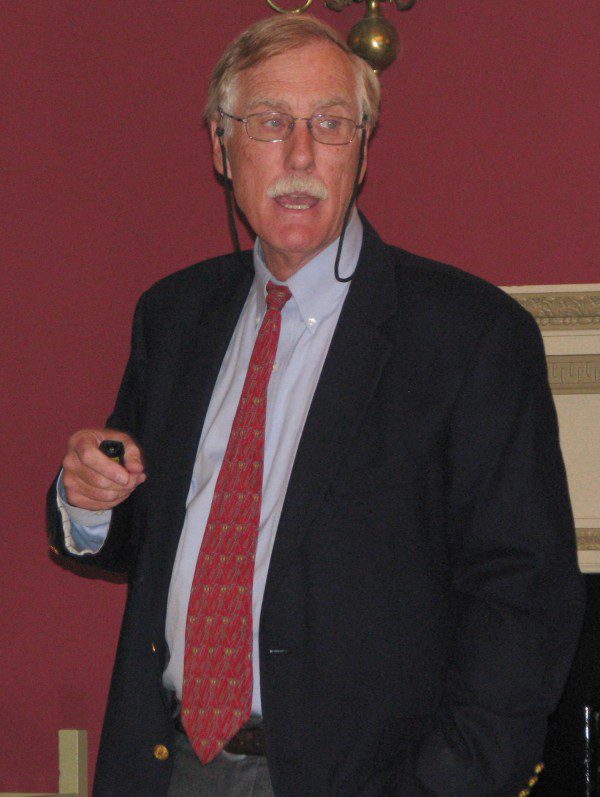

• A University of Maine law school professor’s study of the program was titled, “BETR is a windfall to a handful of corporations and unfair to everyone else.”

Professor Orlando Delogu’s analysis was published by the Maine Center for Economic Policy, a nonprofit and nonpartisan group that generally supports liberal views.

His calculations showed that in 1998-99, 70 percent of BETR reimbursements went to just 20 firms.

Delogu writes that most of the tax subsidy goes to large, profitable firms that “do not need (but will certainly push for and accept) the subsidy…”

Delogu, a regular contributor on land use, environmental and state tax issues to the Maine Lawyers Review, concludes: “ … some would call these payments little more than corporate welfare.”

In a recent interview, Delogu disputed there is any strong connection between BETR and job creation, explaining that his research shows that in many cases the addition of more efficient equipment meant companies needed fewer people to run them.

“BETR,” he maintained, was “unfair, a give-away to wealthy corporations who often didn’t need or deserve the windfall they were receiving, had no checks to determine whether jobs were really saved or created, and no brakes/upper limits on amounts received.”

• BETR is also criticized by a conservative think tank, The Maine Heritage Policy Center. While generally favoring lower taxes on investments, the group’s economist in 2006 raised the same issue as Delogu did: The bulk of tax subsidies went to businesses that need it the least.

J. Scott Moody points out that only businesses that can afford to buy new equipment benefit from BETR, while “a struggling business on the verge of closing its doors and laying off its workers” won’t benefit from the taxpayer-subsidized program.

King replies

“We never should have been taxing machinery and equipment,” King said a recent interview, “because that’s a direct tax on the means of manufacturing, which is what you want to have in your state.”

He said the idea of dealing with the tax “first came to me in 1993, when I was running for governor, from Buzz Fitzgerald, who is one of my oldest friends and was the president of Bath Iron Works. And we were talking about tax policy and he says, ‘You know Angus, it’s crazy, if we put in a new piece of equipment at Bath Iron Works we have to pay the property tax on it every year whether we’re making money or not. It discourages us from making investments.’”

King said the $1 billion in investments he claims on his web site includes $500 million in expansion by National Semiconductor in South Portland.

“They told us that this particular provision (BETR) was absolutely essential to their decision to build that project in Maine. They were looking at several other sites around the country and around the world and it was the business equipment reimbursement that tipped the balance in Maine’s favor.

“As far as the other half billion,” he said, “there were a significant number of investments in the paper industry over the following couple of years where this made a real difference, so I think that’s a conservative number, frankly.”

King explained he made the claims about BETR under the headline “Jobs” because they are “spin offs” from the investments encouraged by the program.

But he also acknowledged that when businesses add new equipment it often is to lower labor costs.

” Upgrading your equipment may in fact reduce employment in the immediate situation but it keeps the plant there,” King said. “So that’s why I don’t think you can apply, you know, ‘how many new jobs did it create’ because it may have cost you 20 but it prevented the loss of 300. “

Business loves BETR

BETR has huge support in the business community.

In 1997, the cost of BETR was higher than expected, which prompted debate in the legislature over the budget impact. King was forced to consider limits, and some legislators wanted to tie the reimbursements to documented job growth, which was never approved.

But business leaders opposed any substantial changes.

Charles “Chip” Morrison, then head of the Lewiston-Auburn Chamber of Commerce, was quoted in the Portland Press Herald stating that 126 companies in Lewiston made $13 million worth of investments that qualified for $360,000 in tax rebates, while 155 Auburn businesses invested $40 million to trigger $1.2 million in rebates.

Tambrands Inc., for example, spent $36 million to expand its tampons plant, and J.C. Penney bought fixtures that allowed it to display more clothing in its existing store.

Emery Thoren, plant manager at Tambrands, told the paper that the company was planning an expansion at either its Claremont, N.H., or Auburn plant. BETR made the difference, he said.

Tambrands is owned by Proctor & Gamble, one the many Fortune 500 companies that take advantage of the BETR program.

A study funded by a group associated with the Council of State Chambers of Commerce credited BETR and other favorable tax programs in Maine for its finding that Maine “imposes the smallest burden on new investment” of any of the 50 states.

Thirty-eight states tax business property, but a 2002 report by the National Conference of State Legislatures said programs like Maine’s BETR are “quite extensive.”

Performance audit

In 1999, when the legislature was worried about the rising cost of BETR, Senate Majority Leader Chellie Pingree, a Democrat, told the Press Herald, “It’s not a targeted program” in its present form. “I think the Legislature has to look long and hard at whether these tax breaks are targeted enough to do the most good.”

(Pingree has since been elected to the U. S. House, representing Maine’s first district. She is running for reelection.)

Eventually, concern about the effectiveness of BETR and other similar programs prompted the legislature to do just that.

In December, 2006, the state’s non-partisan Office of Program Evaluation & Government Accountability audited 46 of the state’s economic development programs, including BETR.

It ranked them based on their “level of financial and/or performance risk.” The agency considered 13 factors, from whether there is an independent review of the program to whether there are means to measure if it is achieving its goals.

BETR was one of 22 programs ranked high risk. Of those, only five programs were ranked riskier than BETR.

While King says BETR led directly to a billion dollars in capital investment, the audit gave the program a poor grade in “performance measurement.”

“Inadequate performance measurement,” states the audit, “may allow program mismanagement or failure to meet desired outcomes to go unnoticed.”

Like many of the state’s programs sold with the promise of economic development, BETR has been a political issue, a fact anticipated in the OPEGA audit.

The audit states that assessing such programs is “exacerbated by the fact economic development is a highly politicized subject … and the slant taken on reporting results … is often politically based.”

King has little use for the studies of BETR: “I don’t think you need a study to determine that not taxing manufacturing equipment is good public policy.”

Below you’ll find the edited short length, and unedited long length videos of Angus King’s interview with the Maine Center.