The industrial wind lobby was not happy.

Its plans to keep building hundreds of wind turbines in rural Maine were threatened by the LePage administration.

During the summer of 2013, the Department of Environmental Protection, run by a LePage appointee, had made things harder for wind developers by putting more requirements into permit applications.

The wind lobby saw the new requirements as illegal and obstructionist from an administration hostile to wind power. And they believed the red tape would slow down — even kill — the expansion plans of their multi-million-dollar industry.

They needed help and by the summer of 2013, they knew where to go: to their friend and supporter Justin Alfond, the president of the Maine Senate.

The connection between the industry and Alfond was not only philosophical — Alfond, like many Democrats, supports renewable energy — but also political. Two political action committees (PACs) run by Alfond had received $9,100 from the wind industry. Alfond used the money to help Democrats get elected to the legislature, Democrats who then supported him in his bid to be Senate president.

The story of how the wind industry’s problem was taken up by Senate President Alfond, D-Portland, and his staff demonstrates a deep level of coordination between special interests and legislative leaders that often leaves citizens on the sidelines of the democratic process.

As the new legislative session opens this week in Augusta, the tale of what became a bill called L.D. 1750, “An act to amend the Maine Administrative Procedure Act and clarify wind energy laws,” is a case study in how special interests hold sway in the legislature.

The coordination between Alfond’s office and the wind industry on this legislation “is how bills get done,” said Alfond. “It’s very typical. Sometimes it’s me who brings a problem to the advocacy groups, sometimes it’s them that bring the problem to me.”

But what’s “typical” to Alfond is undemocratic to Alan Michka, a FedEx pilot who makes his home in rural Lexington Township. For several years, Michka’s been working — without success — at the statehouse with neighbors and friends to undo provisions of the state’s Wind Energy Act that they believe took away their power as citizens to affect where wind towers are built.

“I went into this in the statehouse with this idea that it was a fairly level playing field, they were all looking out for the people of Maine,” said Michka.

“After spending a couple of years at the statehouse, it wasn’t about us at all,” said Michka. “It’s about the people who have money and influence, several large law firms and corporations and people who can make donations.

“I’m embarrassed that I thought I was even in the same ballpark with these people.”

To document the story of LD 1750, the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting reviewed hundreds of pages of emails among Alfond, his staff and wind industry lobbyists and lawyers and interviewed the major players on both sides of the issue.

The search reveals:

Wind industry lobbyists and lawyers enjoyed unfettered access to Alfond and his staff before and while the bill made its way through the legislature.

Wind industry lawyers and lobbyists provided the text of the bill at Alfond’s invitation.

Alfond relied on the industry to direct him and his staff as the legislation was written, rewritten and debated.

Alfond and his staff asked wind industry insiders to help them manage uncooperative Democrats who didn’t like the bill and strategized with them about who should testify in favor of the bill.

‘The bill is in’

Alfond said that in mid-2013, “I went to the renewable energy folks and said I’m interested in doing something proactive to support the renewable industry this session.”

What they needed was a law to undo actions taken during the last year by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) that made applying for a wind power development permit more onerous.

In a Sept. 27, 2013 email to an Alfond staff member, wind industry lobbyist and attorney Dan Riley argued that the DEP’s new requirements made a mockery of Gov. Paul LePage’s LD 1, which aimed to decrease red tape for businesses.

Riley and other attorneys from the law firm Bernstein Shur who worked for wind developer First Wind and the Maine Renewable Energy Association had a solution: a bill that would overrule the DEP action. A bill that they gave to Alfond to submit to the legislature.

Later that day, Alfond’s chief of staff, Michael LeVert, emailed Riley and some of the other lawyers: “The bill is in. Pres. Alfond is sponsor. Talk with you all soon.”

The bill would do four things: ensure the DEP followed existing law when composing application requirements for wind projects; require DEP decisions be based on the opinions of experts; stop the DEP from requiring wind projects to provide proof of their energy benefits; and ensure that wind power energy, environmental and economic benefits are taken into account by the DEP.

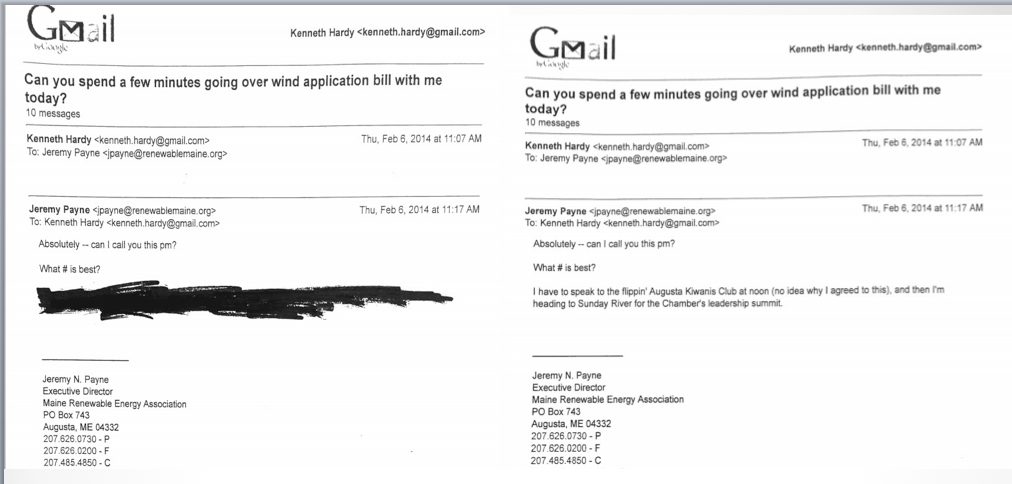

The emails show that industry representatives, including the Bernstein Shur lawyers; lobbyist Jeremy Payne, head of the Maine Renewable Energy Association; and Juliet Browne, a First Wind attorney at Verrill Dana, were asked many times by Alfond’s staff for their comments during the bill’s progress. In turn, the wind industry submitted editing changes and an amendment, most of which were adopted by Alfond.

For example, on Nov. 5, 2013, Alfond’s Chief of Staff, Michael LeVert, emailed two Bernstein Shur lawyers and Payne with the description he had written of the bill for Alfond to use when he talked about the legislation.

“Do you have a minute to give me your thoughts on this?” he asked.

One week later, Payne sent LeVert back a response that contained “some edits for your consideration.” The edits contained strikeouts and substantial rewording of the bill’s description.

Conversely, the bill’s opponents said Alfond’s office did not solicit input from the largely rural groups that oppose wind power or who believe the state’s wind power laws deny them meaningful input into where projects are built.

As the proposed bill became public, interest groups and citizens objected to the provision that would mean agencies could only use experts’ opinions when making permit decisions.

Alfond and his staff had initially not understood just how much the wind industry’s bill hamstrung all regulatory agencies and denied citizens meaningful participation in agency decision-making.

Because of that problem and a second one the bill had to be revised or risk defeat. The second problem, which particularly concerned agency staff and other legislators, was that when an agency wanted to change the text for most of its application forms, it would have to go through a complicated, public process called “rulemaking.”

Browne, First Wind’s lawyer, sent Alfond suggested text for an amendment. Alfond ultimately adopted it, changing nothing in the 248 words she supplied.

On Feb. 13, 2014, Alfond and the wind industry had run across a fresh problem: an Op-ed column, “Bill favoring wind industry threatens to muzzle Maine citizens, regulators,” was published in the Portland Press Herald. The column slammed the Alfond bill.

So the bill’s proponents came up with an idea: write an opposing op-ed and get it published under the name of the Associated General Contractors, a group whose members benefitted from the construction of wind towers.

Hardy, the Alfond aide, discussed that idea on Feb. 14, 2014, in an email to lobbyist Payne and Alfond press secretary Erika Dodge.

Payne responded that he had “connected” with the contractors and “this is likely something they can submit.”

Payne suggested that either he or Dodge could write it. Alfond’s office eventually did the drafting.

The draft was forwarded to Payne, who edited and then forwarded it to the contractor’s group, which later decided not to publish it.

On Feb. 18, the bill’s hearing was held at the legislature’s Energy, Utilities and Technology Committee. Alfond’s office had earlier asked the wind industry to turn out supporters for the hearing.

“Are you guys lining up people to testify on the wind permitting bill? We want a good showing,” wrote Alfond aide Hardy to Payne.

Seven supporters of the bill testified, including Alfond, wind power developers and contractors.

Nineteen people testified against the bill. Their messages were variations on a theme: Don’t treat some citizens as second-class while granting favored status to special interests such as the wind industry.

Two days after the hearing, attorney Browne wrote an email to Alfond: “Thank you for your great work on the wind bill!”

“Thank you and I really appreciate all the assistance you’ve given me and Ken,” replied Alfond, referring to Ken Hardy, his policy director.

By April 1, the Energy Committee had finished considering the bill and voted to pass it, 7-6. The majority on the committee — all the Democrats but one, Rep. Roberta Beavers, D-South Berwick — approved it with an amendment from committee chairman Sen. John Cleveland, D-Auburn, that removed many of the original bill’s provisions, including the one that limited public participation. Despite being largely rewritten, the amended bill still gave the wind industry much of what they wanted.

Drumming up votes

The Senate then passed the bill with unanimous Democratic support. But Alfond lost a significant number of Democratic votes in the House: In the first House vote on the bill, on April 8, it was defeated when 19 Democrats joined Republicans and voted against it. A vote to reconsider the bill was then held, and four of the House members who had just voted “No” switched their votes to support reconsideration.

In a move often used when leadership wants time to drum up more support, the bill was then tabled for a later vote. At 8:01 p.m., Hardy, Alfond’s policy chief, emailed lobbyist Payne and lawyer Riley. The email subject line read “Call list,” in boldface type. Hardy asked them to contact recalcitrant Democrats.

“Jeremy, attached are the member (sic) to call regarding 1750. They are planning on caucusing in the house again tomorrow morning … The President is also calling through the list,” wrote Hardy.

Ten of the Democrats who had initially voted against the bill were on the list, nine of them with their phone numbers.

Three days later, on April 11, the House voted again on the bill. This time, seven legislators who had previously voted “no” switched their votes and the bill passed. The Senate then passed the bill again on the 17th and Gov. LePage vetoed it on the 29th.

Alfond was unable to get the 24 votes he needed in the Senate to override the governor’s veto. He could only get 20, and the veto prevailed.

Cozy bipartisan relationships

L.D. 1750 was a special-interest bill written by a politically powerful industry, promoted by a prominent legislator and passed despite overwhelming public opposition at its hearing.

In this case, a Democratic legislator promoted the bill, but this sort of cozy relationship happens on both sides of the aisle.

There has been much documentation over the last five years, for example, of the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC’s, influence on Maine Republicans. Like the wind industry, corporate champion ALEC has provided Maine lawmakers with the text of legislation it wanted passed on issues ranging from public education to voter identification.

Lobbyists like Payne say the coordination between lawmakers and such interests is the way things work.

“It’s Legislation 101,” said Payne. “You express a concern or an idea … you discuss it with potential sponsors, or with people whose opinions are important to involve, determine whether they share your concern. Sometimes they say ‘We’ll draft it,’ other times they’ll say ‘You draft it.’”

Alfond said the methods he and his staff used to promote L.D. 1750 were common. That includes writing op-eds for others to pass off as their own work.

“Other groups have drafted op-eds for me, I draft op-eds for groups,” said Alfond. “Everyone wants to make sure that … people are repeating the same things for hopefully positive results.”

But others take a darker view of the way things work under the Statehouse dome.

Democratic Rep. Ralph Chapman, D-Brooksville, who has been a critic of special interests’ influence in the Statehouse, voted against L.D. 1750. He said he’s concerned about “the degree to which legislators are corporate clients, rather than spokespeople for the people they represent.

“A lot of major legislation is written by law firms representing the clients whom the legislation is designed to help,” said Chapman. “Sometimes it’s the case that help to those clients is help to the state — and sometimes it’s not.”

Lexington Township resident Michka reflected on how hard it has been for citizens like him to gain traction in the statehouse.

Michka said, “I will tell you one thing that a legislator said to me, a Democratic legislator. He told me, ‘We don’t want you here. We say we do, we act like we do and we welcome you, but in truth we don’t want you here. In truth you clog up the works and make us feel bad. We don’t analyze bills so much as we rationalize.’

“If democracy is about citizens,” said Michka, “then this isn’t really democracy.”