AUGUSTA — A state economic development program that costs Maine $12 million a year cannot be credited with creating any new jobs or achieving any of its desired outcomes, a legislative watchdog reported Wednesday.

The Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability (OPEGA) completed an 18-month evaluation of the Pine Tree Development Zone program and reported its findings to the Legislature’s Government Oversight Committee. The bipartisan committee is considering recommendations in case the state decides to extend the program beyond its statutorily defined conclusion in 2018.

“We found that the current design does not adequately support achievement of any of the program’s desired outcomes,” the OPEGA report said.

The report supports the findings of a 2012 investigation by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, which identified some of the same flaws as the OPEGA report.

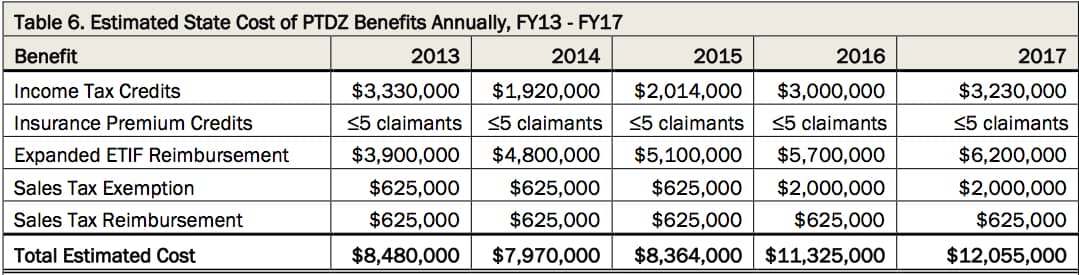

The Pine Tree Zone program, created in 2003 as a way to spur economic activity in hard-pressed corners of the state, offers reimbursements and tax credits to qualified businesses. OPEGA estimated that this year the state will lose $12.1 million in tax revenue through the program.

More than 200 businesses are certified in the program, which under state law is scheduled to stop accepting new businesses after December 31, 2018. However, since businesses can continue to receive benefits for up to 10 years, the program will continue to impact the state’s bottom line until 2028.

In exchange for the tax credits and reimbursements, businesses are supposed to hire at least one employee at an above-average wage. They must also declare that they would not be able to grow in Maine “but for” the tax benefit.

However, OPEGA’s interviews revealed that because the state provides businesses with the exact wording necessary to satisfy that requirement, it is meaningless.

“OPEGA has confirmed with stakeholders that much of the business community also sees the ‘but for’ requirement, and the letter DECD (Department of Economic Development) uses as a way to implement this requirement, as having little practical meaning,” the report said.

If the Legislature decides to renew the program or to create a new, similar economic-development incentive, OPEGA recommended that several design weaknesses be addressed. Those include:

- A fragmented administrative system that sees several different agencies delivering benefits

- Loopholes that allow businesses to receive benefits for up to two years before hiring a single employee

- Weakening of the legislation in 2009 to essentially make the entire state a Pine Tree Zone, instead of implementing it in areas experiencing “economic distress”

The legislative watchdog group noted that determining whether the Pine Tree Zone program is cost-effective is impossible due to nuances in how some benefits are calculated and the lack of data regarding actual usage of benefits.

“OPEGA was unable to reasonably estimate these measures of broader fiscal and economic impacts of (Pine Tree Zone) benefits with the data readily available,” the report said. “As a result, OPEGA is unable to provide a quantitative assessment of whether the program’s roughly $12 million annual cost is a good value for Maine.”

George Gervais, the DECD commissioner who oversees the program, emphasized in his rebuttal letter that while the benefits of the program may be difficult to quantify, they are real. He even offered to provide any legislator with a list of Pine Tree Zone-certified businesses in their districts, so that they could each do their own research.

“I would encourage you to look past the process, and bureaucratic minutia, and ask these businesses how a more competitive tax structure has helped them invest and grow here in Maine,” he said.

One of the only lawmakers on the committee who was in the Legislature when the original Pine Tree Zone legislation was enacted said the report revealed some important flaws in the program.

“I’m glad it kind of worked,” said Sen. Thomas Saviello, R-Wilton. “Its time has come, and its time has gone, unless we want to spend a lot of time fixing something.”

The House chair of the Government Oversight Committee, Rep. Anne-Marie Mastraccio, D-Sanford, concurred.

“This illustrates why we need a long-range strategy for economic development” she said.

The committee plans to hold a public hearing on the report in September.