Even as a sprawling new multi-town collaboration embarks on a journey to reach consensus around a Machias dike replacement, a federal environmental agency has put up roadblocks to any option other than a bridge.

Late last month, the Maine Department of Transportation announced that it would replace the bridge with a longer-term — but still temporary — span intended to last between 15 and 20 years.

MaineDOT then announced it was pausing the federal environmental review process, which had been required because the dike spans Route 1, a federal highway.

Part of the federal review was an Environmental Assessment, a federal document required under national environmental policy rules when significant changes are made to federal roadways. The assessment had been underway for more than a year; it has not yet been published, according to the Federal Highway Administration and MaineDOT.

After seven months of relative silence about the fate of the assessment, the Federal Highway Administration refused to approve MaineDOT’s preferred plan.

In a Nov. 19 letter to MaineDOT, federal officials wrote that they anticipated the project would require a full Environmental Impact Statement, a more complex process mandated when a federal agency expects a project could have a “significant adverse impact” on the environment.

NOAA’s critical remark and other conclusions were included in the agency’s June 14 comment letter to the Federal Highway Administration, the lead action agency for the ill-fated draft. The National Marine Fisheries Service, a department of NOAA, determined that the project would have “significant adverse effects.”

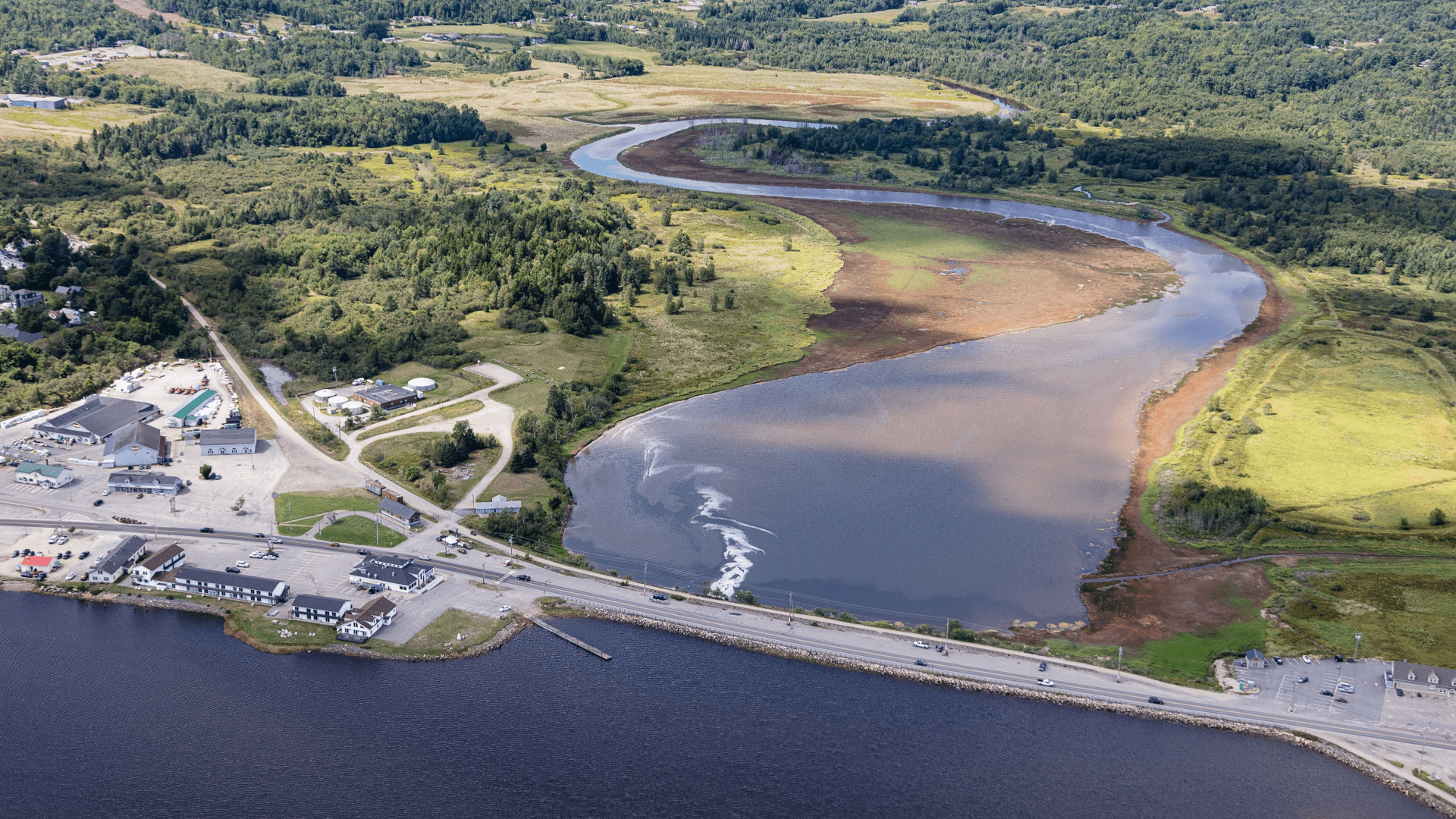

In particular, NOAA recommended the Department’s proposed plan would negatively impact all stages of winter flounder, including sensitive spawning habitat, spawning habitat of migratory Atlantic salmon, as well as a number of natural resources within the Machias and Middle rivers ecosystem, such as the Schoppee Marsh.

The Machias River is one of eleven rivers in Maine designated as a Habitat Area of Particular Concern — a federally designated, high priority area for conservation, management, or research. Machias River supports one of the only remaining U.S. populations of naturally spawning Atlantic salmon with historic river-specific characteristics.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said its determinations were due to “substantial deficiencies” in MaineDOT’s Essential Fish Habitat impact study, a component of the draft environmental assessment.

NOAA concluded that, of the proposals put forward by MaineDOT, a full-span, pile-supported bridge should be selected to replace the current structure. The Department’s preferred choice, an in-kind-replacement with a series of box culverts with flap gates, would prevent tides from passing freely under the structure.

Citing federal environmental laws regarding fish passage of diadromous species and climate change, NOAA further wrote that their recommendations “must be given full consideration,” by the transportation agencies.

The letters were published in late December on MaineDOT’s website along with a raft of other documents detailing the fifteen year-long-saga.

In a November 26 news release and letter to town officials announcing the failed Environmental Assessment process, MaineDOT Commissioner Bruce Van Note vehemently disagreed with NOAA’s findings, but did not reference the agency’s insistence on a bridge. Van Note addressed that concern in a separate letter to the Federal Highway Administration.

“It appears that the use of ‘significant’ may be designed to cause FHWA to require an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in hopes of eventually requiring a bridge alternative,” Commissioner Van Note said in a September 12 letter to Todd Jorgensen, Maine Division Administrator.

In response to questions from The Maine Monitor, a NOAA spokesperson said their determinations are ”advisory” and restricted to the agency’s specific federal mandates under conservation law, only one component considered in the National Environmental Protection Act process.

“The determination of effects under NEPA should be made by the federal action agency (FHWA) after assessing many factors, including the potential impacts of their proposed actions on natural resources, social and cultural aspects, and economic impacts,” wrote Andrea Gomez, Communication Specialist for the Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office.

According to NOAA’s findings, MaineDOT’s Essential Fish Habitat assessment failed to fully account for the operational impacts, even though the assessment indicated the proposed project would permanently eliminate all tidal exchange to the Middle River for the life of the proposed project, 80-100 years.

NOAA estimates that at least 232,200 square feet of existing intertidal and subtidal habitat would be impacted under the Department’s preferred plan.

Among actions to offset the anticipated harms, the agency said Maine DOT would be required to: conduct a wetland delineation survey, assess and remove contaminants from construction and decomposition of the dike and to mitigate losses to account for both permanent and temporary habitat losses over the 3-4 years of construction.

MaineDOT’s latest about-face plan to erect a new, more permanent span to ensure travel along the corridor kicks the decision about a permanent replacement down the road — and avoids dealing with such potentially costly mitigation and a host of other issues inherent in an arduous Environmental Impact Statement process.

But concerns remain about how Machias, other affected communities, and shell fishers will mitigate ongoing flood risks not resolved by the new more durable span, which is expected to be built next year.

On March 10, 2024, Upper Machias Bay experienced the ninth “100-year flood” in six and a half years, and the civil-war era dike remains fragile, according to Tora Johnson, Sustainable Prosperity Initiative director for the Sunrise County Economic Council.

Recent storms have caused at least $10 million in damage in the area, according to Tora Johnson, director of the Sunrise County Economic Council’s Sustainable Prosperity Initiative. Plus another roughly $1.5 million in funding in the form of grants from NOAA and various foundations to pay for studies, reports, and plans.

Then there is the $2 million price tag for the new, temporary span, and ever-rising costs for the eventual permanent structure, estimated between $23 and $30 million, depending on which alternative is eventually chosen and inflation, according to MaineDOT estimates.

With community input, design, permitting, regulatory issues — and the possibility of legal challenges all around — construction of a more lasting solution will be years away.

Meanwhile, the 150-year-old timber and stone dike foundation gets lashed anew by the sea with every storm.

In the past, MaineDOT, with assistance from FEMA, has made the repairs necessary to keep the dike foundation from washing away completely. Should that happen, the result could be inundation of hundreds of acres of land owned by about 54 Middle River residents upstream of the structure.

“A catastrophic failure of the dike would have significant impacts on downtown businesses and on the community because it would require rerouting Route 1 traffic for an indefinite period of time, breach the Downeast Sunrise Trail, and make a colossal mess,” said Johnson in a later email.

The possibility of Middle River properties flooding is a major reason why MaineDOT prefers an in-kind-replacement of the dike, since a bridge would have the same impact, gradually, or not so gradually, returning upstream farmland to wetlands, depending upon the bridge’s design.

Marshfield residents Stephanie and Joey Wood have lived along the Middle River for 30 years. About 1,000 bales of tidal hay are harvested along their property’s shore each year by blueberry farmers, hay that a full-span bridge — or a failed dike — would put underwater.

The worst part, Stephanie Wood said, is being left in the dark.

“This is what’s been going on for the past, oh, my God, 15 years or more,” Wood said. We’re never notified about meetings…they don’t let us know anything.”

According to Van Note’s letter to FHWA, the design and installation of the new temporary span “will be done with consideration of adjacent properties and business owners, as well as other nearby resources.”

Johnson said the new span is intended to assure mobility but not to prevent flooding, either to Machias or Middle River properties. That leaves only the rapidly deteriorating and vulnerable dike to hold back flood waters.

The Maine Monitor asked MaineDOT if it will continue to make dike repairs after the new temporary span is erected, given the likelihood of future — possibly devastating — damage to the dike and subsequent flooding. The written response from Communications Director Paul Merrill was unclear.

“MaineDOT will continue to make essential repairs to ensure continued mobility along Route 1 through Machias,” said Merrill.

With some town structures still not fully restored after last winter’s historic flooding, town officials acknowledge a total dike failure is an ongoing concern. But with the new Upper Machias Bay Master Plan Project firmly established and widely supported, community leaders remain optimistic.

There are about 39 individuals formally signed on as members of the community-led effort, including representatives from: Machias and four other surrounding towns, soon to be named Middle River resident(s), the Sunrise County Economic Council, consultants, four conservation groups, and various federal and state agencies, including NOAA, and MaineDOT.

The group, expected to meet for the first time in January, is tasked with reaching consensus on plans for the dike, an issue that has been divisive for nearly fifteen years.

“It’s not the kind of process that can be rushed,” said interim Machias town manager Sarah Craighead Dedmon. “But I think it’s kind of, kind of revolutionary…to drive these regional solutions and with the help of a major state entity.”

Correction: This article was updated on Jan. 19 to clarify that the temporary structure would be a bridge, not a dike, and to clarify that damage from recent storms is not necessarily attributable to issues with the dike. It has also been updated to clarify attribution for funding for the structure, the possible effects of a failure of the dike, and recommendations made by NOAA.