The specter of fraud has shaded Maine’s public defense system for the past three years while lawmakers and a hired consultant investigated the state agency that oversees court-appointed lawyers for Maine’s poor.

The largest probe yet is now underway into the financial management of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services and it is expected to take at least a year to complete.

The independent Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability (OPEGA) announced on Dec. 10 its plans to investigate five broad areas of financial “risk” in the state’s public defense system, which legislators on the Government Oversight committee unanimously approved.

OPEGA Director Danielle Fox confirmed her staff will investigate some highly specific questions, including whether the state has an adequate system to identify attorney billing inaccuracies and whether defendants are treated equally in all counties when the court determines if they qualify for an attorney.

The findings will remain confidential until OPEGA releases the report. In the meantime, here are five things to watch for in this investigation during the course of 2020.

1. Records and payments

OPEGA will have access to records that were previously shielded from lawmakers and the public under the state’s public records law.

Matthew Kruk, the principal analyst with OPEGA assigned to lead the review, and his team will be able to review documents that the commission would otherwise be allowed to keep confidential, including the commission’s evaluation of attorneys.

This includes a report in the possession of Executive Director John Pelletier of the daily hours billed by some of MCILS’s highest paid attorneys. The report encompasses a portion of the 33 attorneys flagged in 2019 for collectively billing the state $2.2 million more than expected across a period of five years. It also underpins Pelletier’s conclusion to lawmakers last spring that there was no “evidence demonstrating fraud” in the attorney billing system.

Pelletier denied the Maine Monitor’s public records request to see the report in October 2019. A substantially broadened request is pending with the commission.

Fox told lawmakers last month that OPEGA had already identified that it would look specifically at whether state employees at MCILS had procedures to verify the accuracy of hours submitted by court-appointed attorneys on invoices. It also will examine whether the agency was able to identify accidental or purposeful overbilling.

A report by the state Controller’s office in March 2019 concluded — from a random audit of 40 invoices — that MCILS was properly processing payments to attorneys. It did not look into the accuracy of the individual charges on the invoices, but OPEGA could review them, Controller Doug Cotnoir previously told the Maine Monitor.

The accuracy of attorneys’ bills came under renewed scrutiny after the Maine Monitor reported that a new alert system had sent out more than 800 notifications for days attorneys billed the state in excess of 12 hours within a four-month window. Most of those lawyers also did not respond to a requirement that they explain their high hours.

Fox said that OPEGA had also not ruled out looking at the accounting records of private attorneys and law firms that provide court-appointed counsel. This would potentially show if there were billing conflicts with attorneys’ private and federal work and the time they billed on state court-appointed cases.

2. Accelerated review

The initial timeline given by Fox would put the results of the investigation at least 12 months out, but lawmakers and eight newly appointed commissioners to the MCILS board are already discussing whether that timeline can be accelerated to bring change in 2020.

Commissioners Roger Katz, a four-term Republican state senator, and Michael Carey, a four-term Democratic state representative, are simultaneously leading their own review of MCILS’s billing practices. They are exploring whether there are affordable and quick changes that could be implemented to improve financial oversight at MCILS, based on models in other states, Katz said.

Katz and Carey sent a pair of letters to the legislative Government Oversight and Judiciary committees to request their support in prioritizing OPEGA’s review of MCILS and an earlier release of a report and findings.

“I don’t pretend to suggest what their priorities are, because I don’t know what else is on their plate,” said Katz, who previously served as chair of Government Oversight. He went on to say, “It’s really important the public have confidence in the integrity of the system.”

Members of the Judiciary Committee unanimously agreed on Wednesday to also request the OPEGA investigation be prioritized, while putting a two-month pause on its own. A deadline of March 2 was set for the MCILS commissioners to bring recommendations to the committee for legislative amendments this session.

The decision to wait will leave lawmakers just 1½ months to draft, amend and vote on bills before the session is scheduled to end on April 15.

Chair Sen. Michael Carpenter (D-Aroostok) said he anticipated reform proposals to the state’s “Lawyer of the Day” program that is available to all defendants at their first appearance, how defendants waive their rights to an attorney and potentially a pilot public defender office.

“There’s no doubt there’s going to be a time crunch,” Carpenter said on Wednesday.

3. Who can afford an attorney?

A substantial piece of OPEGA’s financial investigation will include whether there is consistency in how defendants are approved to receive a state-paid lawyer.

In the landmark case Gideon v. Wainwright, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that any person too poor to hire a lawyer could not be guaranteed a fair trial unless counsel was provided. It is the state’s obligation to pay for counsel for poor criminal defendants, and Maine has extended that right to juveniles and parents in child protection cases.

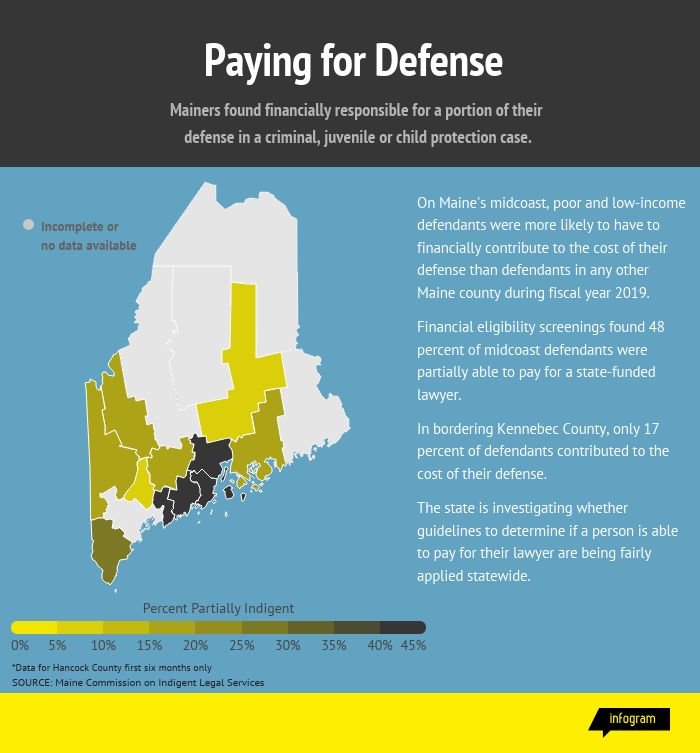

In practice, the right to an attorney has not been equitably applied across Maine. There is variation in the approval rate for state-paid representation between county courthouses, even where the median household income is similar.

Defendants who apply for a state-paid attorney in a court on Maine’s midcoast — including Belfast, Rockland, Wiscasset, Bath and West Bath — or are detained in Two Bridges Regional Jail are least likely to be approved for free lawyers.

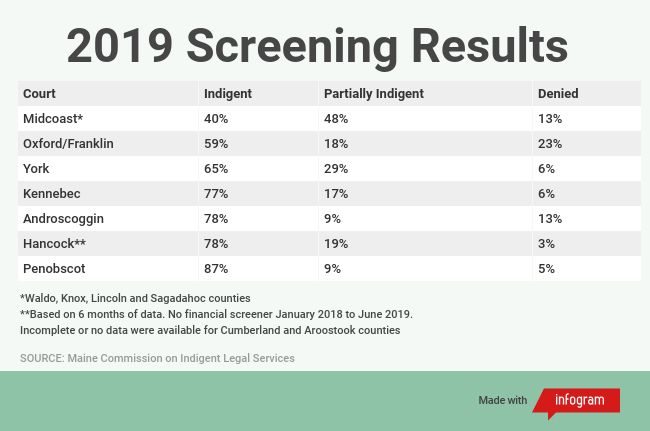

Only 40 percent of Midcoast defendants screened for financial eligibility were found to be too poor to pay for a lawyer in fiscal year 2019. Statewide, it was 70 percent.

High levels of employment on the midcoast and a rising minimum wage factor into why fewer defendants in the four coastal counties qualify for a free lawyer and instead are placed on a repayment plan to pay for a portion of their defense, said Moira Paddock, who has been the financial screener for the midcoast courts since 2007.

Court-appointed attorneys are supposed to be approved based on a sliding scale of the defendant’s income, cash assets and the severity of their crime.

However, in areas with similar median household incomes — roughly $50,100 in the midcoast county of Waldo and neighboring Kennebec County in 2017 — there can still be wide variations in approval for a state-paid lawyers. On the midcoast, 45 percent of applicants screened for attorney eligibility were approved that year, while 75 percent of all applicants in Kennebec were approved.

Defendants supply financial information under the penalty of perjury to a financial screener employed by MCILS, who makes a determination to the judge as to whether the person is too poor to afford to retain an attorney, partially unable or able to afford their own lawyer. The judge may overturn the financial screener’s determination.

Fox said OPEGA’s investigation will include a review of when judges are accepting or overruling financial screeners’ determinations of whether a defendant should receive a state-paid lawyer.

“It’s easier to just approve everyone and then you don’t have to do collections,” Paddock said.

4. Recouping costs

Attorney fees are paid to MCILS only from defendants who are found partially capable of affording an attorney, and the amount collected has never come close to matching what’s spent.

MCILS spent $19.6 million in fiscal year 2019 and collected $1.2 million from defendants determined to be partially indigent — recouping 6 percent of total expenditures for the year.

OPEGA will investigate whether MCILS is reasonably and consistently “determining, ordering and monitoring payments toward counsel fees” by defendants determined to be partially unable to afford their own attorney.

Commission records again show a wide variation between courthouses. The percentage of people found to be partially able to pay for their defense was highest on the midcoast, 48 percent, and lowest in Penobscot and Androscoggin counties, 9 percent, in fiscal year 2019. (Counties that did not have a financial screener for all 12 months of the fiscal year were not included).

Sen. Lisa Keim (R-Oxford), who led a legislative working group on how to improve MCILS in 2017, has long wondered if partial repayment plans were being underutilized.

“There’s likely a significant number of people out there that could be considered partially indigent and yet we’re not seeing that. It’s important that people have skin in the game; I think there will be better outcomes if defendants take financial responsibility in some measure,” Keim said.

5. Short-session action

Lawmakers and commissioners will have several vehicles to react to known issues with Maine’s public defense system this session.

The Judiciary Committee carried forward to the short session a bill by Rep. Barbara Cardone (D-Bangor) to make broad changes to the state’s public defense system. Some reforms may also be spread across other bills already in front of the committee to avoid attracting too many interest groups into a single bill hearing and slowing the process down, Carpenter said.

Rep. Donna Bailey (D-Saco), co-chair of the Judiciary Committee, emphasized that regardless of the financial inquiry OPEGA was doing, it did not address the crux of the findings of previous investigations, including that there are systemic and potential Constitutional problems with Maine’s public defense system that needed to be fixed.

There was an understanding among the committee members that to reform the public defense system it would likely require a further investment of state funds. The state will need to consider increasing compensation for court-appointed attorneys and making systemic reforms to the assignment and continuity of counsel, said Rep. Jeffrey Evangelos (I-Friendship).

“We’re going to have to spend some money, folks. Justice isn’t cheap,” Evangelos said.

Since its formation in 2010, MCILS has had between three and four full-time state employees. Staff are operating at capacity and do not perform regular in-court observation of court-appointed attorneys. OPEGA’s investigation will look at how MCILS staff responds to “internally identified concerns” and whether there is adequate oversight of Maine’s public defense system.

Pelletier submitted a supplemental budget request for two new staff positions at MCILS. An additional staff attorney would oversee the training and supervision of attorneys and a new financial examiner would review billing and expand the office’s financial oversight.

The request will be considered by the Appropriations and Financial Affairs committee this session.