This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

This is part of a continuing series.

Two-thirds of Maine county jails recorded phone calls between jailed clients and their attorneys at various times since 2014 and provided law enforcement with some recordings, which potentially violated defendants’ constitutional rights, an investigation by The Maine Monitor has found.

As the recording of attorney calls became public in recent years, county sheriffs, a state agency and the company that runs most of the phone systems in Maine jails have taken steps to curb the practice. But they’ve stopped short of a statewide solution.

Ten of the 15 county jails recorded phone calls that jailed defendants made to their attorneys that should have been confidential. At least one recording — though often far more — was made at each of those 10 facilities between 2014 and August 2021, The Maine Monitor confirmed with data, court records and interviews.

Maine’s elected sheriffs wield sweeping power over county law enforcement and jails. They are responsible for all aspects of jailed defendants’ lives, including phone calls to friends, family and lawyers on the jail phone system, which is contracted to private companies.

At least eight counties shared recordings of some confidential attorney-client calls with investigators or prosecutors, according to interviews and records. As many as seven counties burned CDs of the recorded calls while at least three counties gave investigators access to the phone system so they could playback recorded calls, data and court records show.

Responding to disclosures by The Maine Monitor about the recorded calls, multiple sheriffs said the recordings were made and shared unintentionally. They also blamed defense lawyers for not notifying county jails that their phone numbers should be private, and therefore not recorded by the jail.

Some sheriffs have taken steps to identify missing attorney phone numbers and also limited who can potentially listen to recordings of calls. Sheriffs and jail administrators have repeatedly said the calls people in jail make to their lawyers should be private.

The U.S. Supreme Court has long recognized a defendant’s right to confidential communications with his or her lawyer, known as attorney-client privilege. Its purpose is to encourage full and frank communication between attorneys and clients.

Securus Technologies, which provides inmate phone services to most Maine jails, added hundreds of attorney phone numbers to the jails’ phone systems in May 2020 and again in May 2022, records show.

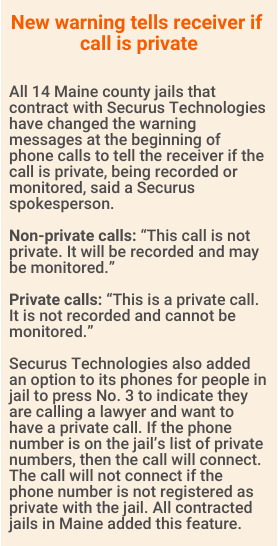

A company spokesperson said new warnings were added in recent years at the start of phone calls to notify the parties if the call is private or if it will be recorded, or if it can be monitored. This is to minimize the chance that lawyers will be recorded.

Securus also added an option in 2021 for people in jail to indicate they are trying to contact a lawyer by pressing the No. 3. The call will not connect if the phone number is not set up as private and will tell the caller this, said the spokesperson. If the call is to a lawyer, it will not be recorded.

All Maine county jails contracted with Securus Technologies made the changes, said the spokesperson.

Meanwhile, Maine’s public defense agency announced plans this month to collect attorney contact information and provide lists of phone numbers that should be exempt from recording to Securus, the jails and the Maine Department of Corrections.

That proposed solution has its own limits. Lawyers who are privately retained or work for civil rights organizations such as the ACLU will be left off the lists provided by the state and would need to register on their own.

Attorneys are required to provide their phone numbers to each county jail where they may represent clients to prevent being recorded. The attorneys must repeat that process should their phone number change. Maine has no process to privatize a phone number statewide.

Securus does not curate statewide lists of attorney phone numbers because each jail is independent, said a Securus executive. The company can make batches of phone numbers and calls to those numbers private. The phone numbers need to be added to each jail, which in Maine means importing a list 14 times.

Securus would prefer that every attorney phone number was private in its phone system and none of the calls were recorded.

“In a perfect world, there would be zero recorded attorney calls,” said the company executive.

“Reducing the number of inadvertently recorded attorney calls requires everyone involved in the process to do their part. The lawyer has to make the private-number request, the agency has to action that request appropriately, and we have to perform our role effectively,” the executive added.

The Securus executive said the company will “have more solutions coming soon.”

Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce said the current system that requires attorneys to register their phone number with each jail is efficient and “requires little effort.” Lawyers must advise the jail when a phone number changes, he said. A statewide list would “be just as likely to have omissions and incorrect numbers” as the ones currently in place at the jails, he said. But he said he would be open to other solutions.

Counties withhold phone records

The Maine Monitor has sought public information about the recordings in various ways since June 2020 and has periodically published articles about the recordings in some counties. This article reports for the first time the extent of the practice across the state.

The Monitor asked all 15 county jails for data about recorded attorney calls. Six counties — Androscoggin, Aroostook, Franklin, Kennebec, Penobscot and York — turned over some data after a public record request. The data shows about 1,000 phone calls between jailed defendants and attorneys were recorded between June 2019 and May 2020.

The Monitor pieced together evidence of recorded attorney-client calls in four additional jails — Cumberland, Piscataquis, Somerset and Two Bridges Regional Jail — through court records and other reporting.

Some sheriffs who refused to release records said they did not consider data about the jail’s phone systems to be government business. Others said it would be a violation of an inmate’s privacy to disclose if the jail had recorded calls with their attorneys.

Cumberland, Piscataquis and Somerset county jails recorded attorneys but have refused to release data showing how many times it might have occurred, records and interviews reveal. Knox County also denied requests for data about whether their jails’ phones recorded attorneys. Washington County said it didn’t record any calls to attorneys from the jail; it refused to provide the data the Monitor requested.

Piscataquis County Sheriff Robert Young disclosed in an emailed response to questions from The Maine Monitor in 2021 that his jail had recorded calls defendants made to attorneys’ cell phones that were not registered with the jail. He did not respond to additional questions about how many attorneys or defendants were affected.

Two counties reveal more recorded calls

Penobscot County in May 2022 released data that shows 24 attorney-client calls were recorded between January 2019 and May 2020. That information came in response to a public records request.

Bronson Stephens of Bucksport is one of the defense attorneys recorded by the jail in April 2020, data shows. Stephens said he sent emails around that time with his phone number to the jail and responded to two requests for attorneys to provide their phone numbers.

“No one told me that there was a recording of that call. I am upset to hear it and unfortunately only somewhat surprised that I was not notified immediately. I am much more surprised that after all this time still, no one has notified me,” Stephens wrote in an email after being contacted by a Monitor reporter in June 2022.

RELATED: Maine lawmakers, defense attorneys say jails ‘must stop’ recording and listening to attorney calls

In York County, meanwhile, the The Maine Monitor sued the county to seek the release of information on attorney calls it recorded at the local jail. Litigation is ongoing over the Monitor’s request that the county release records that would show how many attorney-client phone calls were recorded.

York County released a subset of data on recordings of calls between inmates and non-lawyers. The data shows that two jail officials elected to save, burn to CDs or “playback” — a term that means listen to — recordings of those calls. There is no evidence that the calls were between attorneys and their clients, except for a single call in 2019.

That one call between an attorney, William Adams, and a jailed client in June 2019 was recorded and later burned to a CD. That CD was subsequently shared with a prosecutor, according to Adams. He said the prosecutor stopped as soon as he had begun listening to the recording. The prosecutor then notified Adams and the judge in the case.

In August 2020, York County officials added a warning to the beginning of calls from prisoners at the jail. Lawyers were instructed to call a number before accepting calls from their jailed clients, otherwise the call would be subject to monitoring and recording, emails obtained through the Monitor’s lawsuit show.

Some sheriffs demand change

Waldo County Corrections Administrator Major Ray Porter sought to prevent all Maine jails that contracted with Securus Technologies from recording lawyers in May 2020.

Porter secured a list of 439 phone numbers of attorneys participating in the state’s public defense program after receiving questions about whether attorney-client phone and video calls were private at the jail. Securus Technologies added the phone numbers Porter collected to a do-not-record list and applied it to each Maine jail the company served, emails show.

“Over here in Waldo County, we call (jailed defendants) our friends and neighbors,” Porter said in September 2021. “… I have zero tolerance for anything that would infringe upon somebody’s right to privacy.”

Porter said Securus reviewed the jail’s phone logs in 2020 and didn’t find any recordings of calls to lawyers’ phone numbers. Waldo County officials denied the Monitor’s requests for call data in 2020 and 2021 that would show if public defense lawyers were recorded by the jail.

Some sheriffs in the past two years also have limited access to recordings. In Oxford County, Sheriff Christopher Wainwright limited access to the jail’s administrator and assistant administrator, who regularly encounter local defense lawyers at the jail and would recognize their voices and stop listening, he said. Hancock County also limited access to its jail administration, Jail Administrator Timothy Richardson wrote in response to questions.

Securus verified that the Oxford County Jail did not record any attorney phone calls between June 2019 and June 2020, according to an email shared with The Maine Monitor.

When Somerset County switched from the phone provider GTL — a prison telecom company that recorded some calls to Maine lawyers as well — to Securus Technologies in 2021, the county downloaded a phone directory from the Maine State Bar Association, and made its jail administrator and assistant jail administrator responsible for approving and reviewing all requests to download recordings of prisoners’ calls. The jail does a monthly audit to verify that these processes work, Somerset County Sheriff Dale Lancaster wrote in a statement.

Cumberland County twice had the state bar association email reminders to lawyers that it is their obligation to register all their numbers with Securus.

Right to an attorney

It is common practice for jail officials and law enforcement personnel to monitor calls prisoners make to people other than their attorneys. Signs posted near phones and audio messages at the beginning of calls warn that their calls are not private, and will be recorded and may be monitored.

The privacy of people in jail only extends so far, according to Joyce, the Cumberland County sheriff.

“Law enforcement is frequently assisted by the lawful monitoring of inmate telephone calls. Many criminal acts have been proved and also prevented by monitoring such telephone calls,” Joyce wrote in response to questions from The Maine Monitor this month. “… Obviously, we want to avoid interference in the attorney/client relationship and do so when we are aware that such communications are occurring.”

Jail investigators are exempt from part of Maine’s wiretap law, and can intercept and use prisoners’ phone calls, but the law also says it “does not authorize any interference with the attorney-client privilege.”

In a letter to state legislators earlier this year, the Maine Sheriffs’ Association said proposed legislation to place new limits on recording and monitoring inmates’ phone conversations would threaten the safety of domestic violence victims, allow defendants to continue to commit crimes and enable drugs to be trafficked into the jails.

“Domestic violence victims deserve to be protected from intimidation and threats, calls that can and should be caught in recordings. Arranging to smuggle in contraband and providing drugs to other inmates has been prevented by catching these arrangements in taped phone calls,” the sheriffs wrote.

Within the batches of recordings made by Maine’s jails are calls jailed defendants make to their lawyers. Maine corrections standards mandate that jails allow defendants to confidentially consult an attorney by mail and telephone, according to policy.

The sheriffs are looking at the issue backward, said Justin Andrus, the executive director of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services, a state agency responsible for providing lawyers to defendants who cannot afford to hire their own attorney.

“The clients who are in the jail have a constitutional right to unimpeded communication, unrecorded communication, with counsel. The jails don’t have a corollary constitutional right to the monitoring they want to do,” Andrus said.

If sheriffs cannot accomplish the monitoring they want to do in the jails without infringing on defendants’ constitutional rights, then they need to stop the recordings, he said.

Lawyers weren’t told

In late April 2021, the Kennebec County sheriff insisted his jail did not record calls between defendants and their attorneys.

But that summer, Sheriff Ken Mason released data showing the jail recorded 154 calls to attorneys between 2019 and 2020. When presented with the county’s own data, Mason dismissed the recordings as insignificant since, even if they occurred, he said the calls were just a sliver of the thousands made by jailed people to attorneys in a year.

He also declined to assign blame. It could have been the fault of jail staff, Securus Technologies, which provides phone services to jailed defendants, or defense attorneys, if they failed to notify the jail that calls to them must be private, he said.

“It was my complete opinion — and my trust in the system and how it works — that we do not record privileged phone calls on purpose,” Mason told The Maine Monitor, when asked about the conflicting information during an interview in 2021. “We don’t do it to get the upper edge because that is illegal. That will just squash a case.”

Additional data released by Kennebec County shortly after that interview shows a sheriff employee and other law enforcement actually went a step further and selected to save, playback or burn CDs of two attorneys’ calls with their jailed clients. Both attorneys said they weren’t notified that their phone calls had been recorded or accessed in those ways. They learned of the breach from a Maine Monitor reporter.

Maeghan Maloney, the district attorney for Kennebec and Somerset counties, said the jail’s phone system blocks investigators from listening to attorney-client phone calls. The jail doesn’t record and investigators cannot listen to calls to phone numbers designated as private, she said.

Maloney acknowledged that there was one instance on April 21, 2020 when a sheriff’s detective working in her office elected to “playback” a recording of a call between J. Mitchell Flick, a criminal defense attorney, and his client, who was in the Kennebec County Correctional Facility. The detective didn’t know the recordings included an attorney, Maloney said. Maloney said the detective listened briefly to ensure that the defendant, with a history of domestic violence, wasn’t contacting a victim.

“(He) doesn’t remember the call, but he knows if he heard a male voice, he would automatically move on to the next call. There was no reason to listen to calls to men,” Maloney said in an email to The Maine Monitor.

Officials in other Maine counties and courtroom testimony by a top Securus employee show the designation “playback” in the data means a recording was listened to. The data doesn’t say how long the recording was listened to.

Maloney insisted investigators in her office do not, as a practice, listen to recordings of attorney calls with their jailed clients. But they do listen to recordings of jail calls by defendants to non-attorneys, such as in domestic violence cases to ensure they are not contacting victims, she said.

Domestic violence investigators are responsible for monitoring the phone calls and video chats of all people in jail charged with domestic violence or sexual assault, according to her office’s policy. If a “defense attorney call is accidently heard,” the investigator is to turn off the recording, write down what was heard and notify the prosecutor, who will notify the defense attorney and the court, the policy states.

The Kennebec and Somerset counties district attorney’s office is the only prosecutor’s office in Maine with a written policy on how to handle the discovery of a privileged recording. The rest have a “practice” to discontinue listening and report the recordings to the lawyer, said York County District Attorney Kathryn Slattery.

Flick said he was not notified that the 2020 call was recorded or had been played. There were 76 additional recordings made by the jail’s phone system of calls with his jailed clients, data shows. Those recordings were also saved and burned to CDs dozens of times by other law enforcement officials, data shows.

Flick has practiced law since 1985 and was only accepting calls from jailed clients on a cell phone. Asked if he alerted authorities of his phone number, Flick said he does not recall. It is possible, he said, that his number was not registered with Securus at the time.

Costs to change

People in jail pay to make phone calls and the jails are paid a portion of those fees. The telecom companies also pay counties some of the upfront costs of installing the phones and monitoring systems, which the counties would otherwise pay for.

Most Maine sheriffs contract with Securus Technologies to install phones and operate a system that charges inmates to make calls. The Texas-based company is one of the nation’s largest providers of prison phone services.

A Maine Monitor analysis of five years ending in 2020 found that the county jails had collectively earned at least $3.3 million from revenue sharing with Securus Technologies.

The money is placed in an inmate benefit fund in each county and must be spent on programming or items that benefit the people in the jail. None can be spent on running the jails.

State lawmakers passed a law this year to cap the price of phone calls at Maine jails and prisons. County jails will not be allowed to negotiate contracts with prices above 21 cents per minute after October. Previously there was no limit on how much jails could charge for in-state calls.

A search for solutions

State lawmakers are now searching for broader solutions to prevent the recording of calls between lawyers and their jailed clients.

State legislation proposed in 2022 said investigators could “not intercept, record, monitor, disseminate or otherwise divulge” calls between lawyers and clients. If prosecutors or investigators accessed or received recordings of those calls, they would be prohibited from participating in the prosecution. That law would apply across the state.

The Maine Sheriffs’ Association opposed the proposed law and wrote that it would “cause irreparable harm to the citizens we’re elected to serve.”

State lawmakers opted to instead study the recording of attorney calls at the jails and discuss possible legislation to be considered next year. The study group’s work began Sept. 7 and a report is due back to the Legislature by November.

RELATED: Study group to scrutinize jail, prison policies amid reports calls to lawyers were recorded

It’s important for the jails to be completely transparent about what’s happened.”

— Zach Heiden, chief counsel of the ACLU of Maine

The recording of attorney calls by the jails appears to come down to mismanagement, said Daniel Pi, a visiting assistant professor of criminal law at the University of Maine School of Law.

“It seems that the jails attempted to take some corrective measures after the fact, but the attempt to correct the lapses strikes me as an implicit admission that mistakes were made,” Pi said.

Lawmakers’ decision to delay action was a missed opportunity to a recognizable problem, which is that the state is not allowed to interfere with people’s communications with their attorneys, said Zach Heiden, chief counsel with the ACLU of Maine. He described the ongoing risk of jails recording attorney-client calls as “utterly stupefying.”

State officials are facing increasing threats of litigation. Lawyers in California, Texas and Kansas have sued Securus Technologies for recording attorney-client conversations. Securus and a private prison in Kansas agreed to a $3.7 million settlement in 2020 for recording attorney calls and sharing those conversations with a federal prosecutor, according to court records. In each instance, Securus denied intentionally recording attorney calls and challenged whether the calls were private.

A similar lawsuit filed by Maine lawyers was dismissed in November 2021.

Heiden and other members of the legal community are watching what Maine officials do next.

“It’s important for the jails to be completely transparent about what’s happened. They need to say whose calls have been recorded, what recordings have been turned over to the prosecutors and most importantly what are they going to do in the future to make sure people’s constitutional rights are respected,” Heiden said.

Initial funding for this project was provided by The Pulitzer Center. The project is also supported by Report for America and Investigative Editing Corps. The Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic at Yale Law School with local support from Preti Flaherty provided legal services for this project.

Samantha Hogan covers government accountability and the criminal justice system for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email: gro.r1766881906otino1766881906menia1766881906meht@1766881906ahtna1766881906mas1766881906.