Doug Dunbar traces the beginnings of his alcoholism to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

He was in Washington D.C., working as director of communications for then-U.S. Rep. John Baldacci. He and others were evacuated from their offices and hunkered down in the apartment of a fellow congressional staffer. The Pentagon had been hit by a plane and no one knew if more attacks were coming.

The next night happened to be half-price wine night at a local bar, and Dunbar and another staffer helped themselves to a lot of it. It was then that he realized that alcohol seemed to help control his obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety.

Dunbar, a graduate of John Bapst High School in Bangor, returned home to Maine and held various state government jobs after Baldacci was elected governor in 2002. Dunbar first worked in the governor’s communications office, then served as deputy secretary of state, and director of communications and legislative affairs for the Department of Professional and Financial Regulation.

Over several years he drank more and more, switching from wine to vodka and then to light beer. He hid cases of beer in the trunk of his car and drank while driving from his state government job in Gardiner back to his home in Hermon. When he got caught, he hired good attorneys to get reduced sentences. He was amazed that no one seemed to know when he got arrested or spent a night in jail.

Finally, after six arrests that included three OUIs, it all came to an end on Oct. 23, 2017. He had left the home he shared with his father to get food at a Kentucky Fried Chicken on Broadway in Bangor when police picked him up for driving drunk. For the next 136 days, he was incarcerated at either the Penobscot County Jail or the Two Bridges Regional Jail in Wiscasset.

RELATED Due Process: Talking justice with Maine’s district attorneys

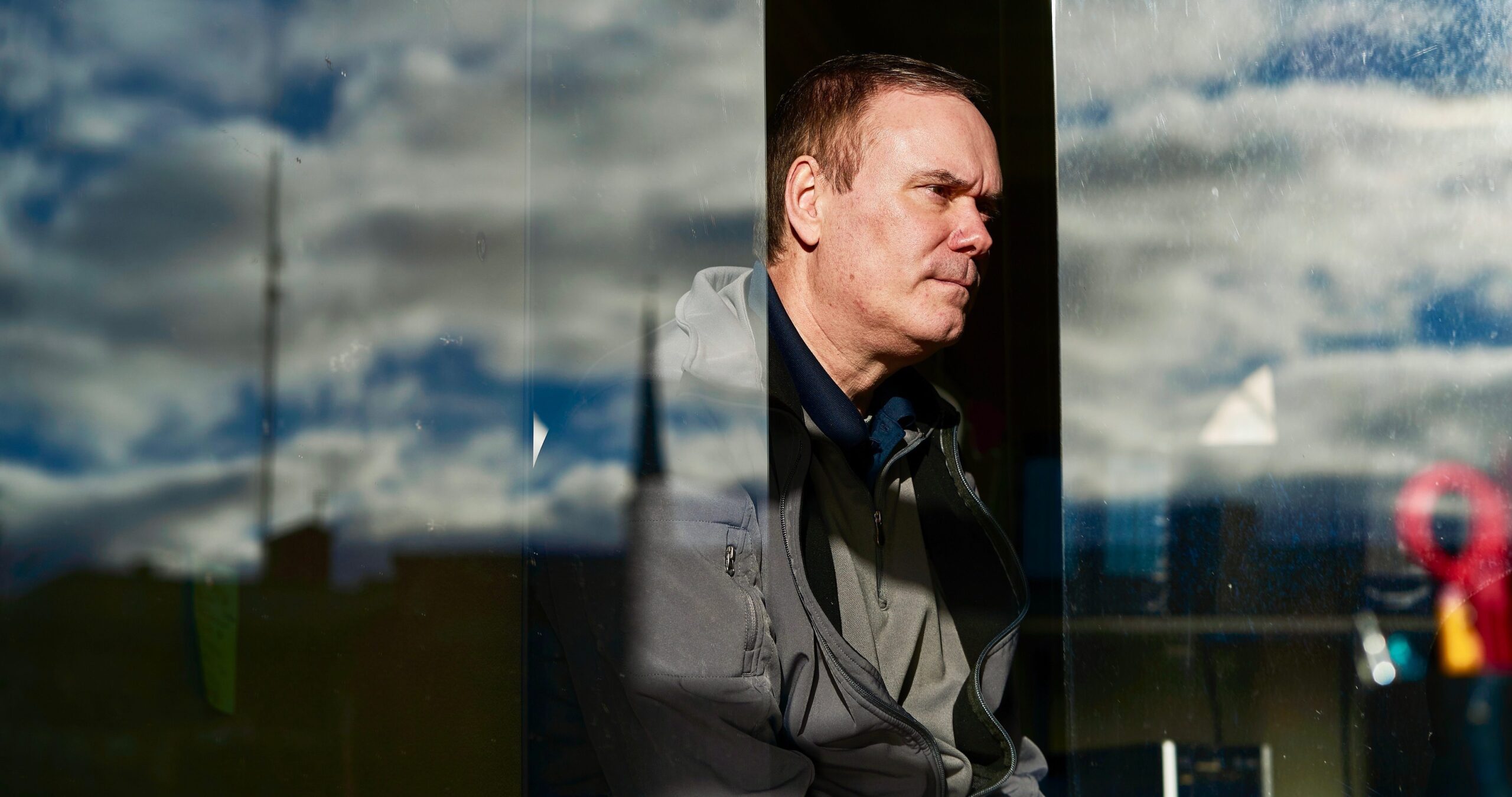

“I am the face of mental illness,” Dunbar said during a recent interview in Bangor. “I am the face of addiction. I am the face of a felon.”

That experience has led Dunbar, 53, to become an advocate for bail reform. While he successfully completed a 15-month program to help him get sober and has a job despite his felony record, what Dunbar saw happening to others — particularly the poor and mentally ill — is what has him motivated to make things better.

“From start to finish in the criminal justice system, we do almost everything wrong to one extent or another,” he said. “Once I got into jail, I wanted to bail everybody out.”

Reducing the number of people in jail who haven’t yet been convicted of a crime is the major focus of the Pretrial Justice Reform Task Force that spent nine months trying to figure out how to “reduce the human and financial costs of pretrial incarceration and restrictions,” according to the charge given the group by Maine Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Leigh Saufley.

Dunbar explains those costs in blunt terms.

“They can’t come up with $200, $500 or $1,000, so they sit there,” Dunbar said. “And then, because they are poor and oftentimes sick, they are appointed an attorney through the indigent legal services system.”

That system has been heavily criticized in recent months by lawmakers and others as dysfunctional, both in terms of billing irregularities and for the disparities in the quality of representation afforded to clients.

Dunbar said that in addition to being stuck in jail, things often happen outside that are beyond the control of someone who – again – has not been convicted of anything.

“If you had an apartment, it’s gone,” he said. “If you had a job, it’s gone. If you were on Medicaid, it’s gone. If you had children, possibly taken. This is if your innocent or guilty. Your life unravels because you can’t come up with 500 bucks in bail.”

Randall Liberty, the Department of Corrections commissioner, agrees, saying when he was Kennebec County sheriff for 14 years, he often wondered how it was fair that someone being held on suspicion of shoplifting could spend a weekend in jail because they couldn’t come up with $100.

He said a risk assessment to determine whether someone is a flight risk or a danger to public safety should replace cash bail.

“That’s one of the larger disparities I see,” said Liberty, who served on the task force.

Bail reform?

At a November task force meeting, there was extensive discussion about one of the most controversial recommendations that came from a subcommittee, but ultimately led to a tie vote by members of the full committee: Eliminate financial, typically cash, bail for low-level, non-violent offenses.

Elizabeth Simoni, executive director of Maine Pretrial Services, a nonprofit that contracts with the state to help assess people who are arrested, pushed to try to convince others on the panel that they should make a recommendation regarding financial bail.

“The bail code does not indicate we should be using money to detain,” she said. “I hate to see us consistently keep putting this off.”

But Alison Beyea, executive director of the ACLU of Maine, said attempts to eliminate cash bail in other states led to “racially divisive decisions” that had the unintended consequence of locking up people of color more frequently because the risk assessments used deemed them too dangerous.

“We would certainly support a pilot project to actually see if it would work and not make things worse,” she said. “We’re watching other states struggle with it.”

Superior Court Justice Robert Mullen, chairman of the task force, suggested asking the Legislature to create another task force to study the issue of bail, but others said they felt it was important to try to resolve the issue.

During the discussion, District Court Judge Valerie Stanfill — who was recently nominated by Gov. Janet Mills to serve on the Maine superior court — suggested amending the bail code to alert judges that they should have a “presumption against cash bail,” in an effort to discourage its use.

Beyea said the issue of bail will again be discussed by lawmakers because a bill was carried over from last session. She said historically “bail was a way of releasing people, not holding them.”

“We’ve become hardened to what it does to someone to spend one night in jail,” Beyea said.

Moving forward

Some of the group’s recommendations are likely to land before lawmakers this session as they look for ways to reform the system. The 25-member task force, which included judges, legislators, county sheriffs, district attorneys, a tribal representative, criminal defense lawyers, the American Civil Liberties Union and victim advocates, passed along 30 recommendations to Saufley and others in a report issued Dec. 20.

In early January, Amy Quinlan, director of court communications for the administrative office of the courts, said Saufley was reviewing the report and that she “did not believe any determinations” had been made as to which recommendations would be backed by the chief justice.

The task force unanimously supported a recommendation for the state to fully fund “robust data development and collection, including release of data to the public” that will shed light on arrests, bail conditions and how long people are in jail before trial. In addition, the data should detail race and gender, the report states.

“Of all items considered by the Task Force, this was the one item that generated the most support and the most discussion,” Mullen wrote in the report. “The subcommittee members and the full Task Force were greatly frustrated by the dearth of available, standardized and reliable data upon which it could make recommendations.”

The report cites Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia as examples of entities that have integrated systems across agencies so that “law enforcement, corrections, the courts, probation and mental health agencies” can share “real-time data” and information.

Other recommendations included:

• Encouraging the use of summonses instead of arrest for non-violent misdemeanor offenses.

• Fully funding an electronic court notification program to remind all defendants of upcoming court dates.

• Establishing “safe place” diversion programs so police officers have a place to take someone other than jail. The report notes that in other parts of the country, these sites allow someone to be evaluated for physical or mental health problems, substance use disorder or housing and employment needs.

“Many felt that arresting and then incarcerating individuals with mental health or substance use disorder for crimes committed while suffering from these conditions was wrong, did nothing to address the underlying causes and failed to properly provide programming and treatment that would stop the criminal behavior,” the report states.

• Mandating and funding “regular racial justice training for law enforcement, bail commissioners, judges, prosecutors, pretrial services, corrections officers, probation officers and defense attorneys.” For the ACLU, this is one of the key recommendations from the task force, Beyea said.

“I don’t believe that would have ever happened a few years ago,” she said.

• Expanding the availability of GPS monitoring for “medium and high-risk domestic violence perpetrators in all counties.” Andrea Mancuso, a task force member and attorney with the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence, said this recommendation is particularly important to her organization.

“Fundamentally, there exists decades of research to support what we know to be true – that the first time an offender is criminally charged is rarely the first incident of abuse,” she wrote in an email. “By the time most domestic violence offenders get to criminal court, they are already ‘repeat offenders,’ if only behind closed doors.”

Task force member Tina Nadeau, executive director of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said although her group supports enhanced data collection, they don’t believe it’s necessary to wait for hard data to make meaningful changes.

“We do feel that data on the setting of bail, focusing on the amount of bail set for people of color versus white people, would be eye-opening and necessary to address discrepancies and disparities in the treatment of people of color in Maine’s criminal legal system,” Nadeau said via email.

In addition, she said the state should decriminalize drinking in public, a task force recommendation that got less than full support, with six members voting yes, four voting no, two voting maybe and one abstention. Nadeau said the charge is “used almost exclusively as a way to patrol and harass people experiencing homelessness.”

“Somehow, lighting up a joint in public is a civil offense, but drinking a beer in public – when the transient populace has no ‘private’ place to drink – is a crime,” Nadeau said. “This is beyond absurd. We should also decriminalize the possession of drugs period.”

Dunbar, who was not a member of the task force but reviewed its findings, said one major flaw of the task force was that it did not include anyone who’s “been a defendant in pretrial status.”

“I’ve grown tired of committees, commissions and task forces that include few, if any, of the people directly impacted by the topic under consideration,” he wrote. “Since my time in jail, my breath has been routinely taken away by government ‘experts’ who know remarkably little about the people, procedures, processes and facilities within our criminal legal system.”

He agreed with calls for better data collection, saying his efforts to get “summonses vs. jailing” data from the Penobscot County Jail has been “almost impossible to access.”

‘Very routine’

Shortly after his incarceration, Dunbar discovered it did not have a legislatively mandated group to keep tabs on what’s going on inside the jail. Every county jail and the state prison is supposed to have a Board of Visitors to monitor how people with mental illness are being treated, Dunbar said.

“Prisons and jails are just such closed environments, closed societies,” he said. “We need more eyes and ears in these places.”

Following Dunbar’s complaint, the county reinstated the group, according to the Bangor Daily News.

Dunbar also actively works to make sure that when a new Penobscot County jail is built, it is not larger than the existing jail. His concern is there will be no new money for programming to help people with substance use disorder or housing needs.

“We don’t need more capacity here because if we build it, they will come,” Dunbar said. “We will fill every last bed, every last cell. I’m convinced of that.”

Another area he’d like to see improved is the time spent with defendants when they first come to court. The criminal justice system is missing an opportunity early in the process to look into whether there are other options for certain defendants – particularly the poor and the sick, he said.

“If you sit in court, you get a sense that there’s a routine,” he said. “Person comes in in shackles, orange jumpsuit. It’s very routine. There’s no opportunity to figure out what’s going on with the guy or gal. What should we really be doing here?”

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, we incorrectly reported the nomination received by Judge Valerie Stanfill. She was nominated by Gov. Janet Mills to fill a vacancy on the Maine superior court. The Maine Monitor regrets the error.