Advocates for poor criminal defendants in Maine say court clerks are appointing ineligible lawyers to handle cases in an attempt to meet the constitutional requirement that people accused of crimes get representation.

The complaints follow a petition submitted to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court on Sept. 20 by two criminal defense lawyers — Rob Ruffner of Portland and Rory McNamara of York — on behalf of a woman who sat in jail for months without being assigned an attorney despite being entitled to one.

Ruffner and McNamara asked the justices to find out whether other indigent defendants were ordered to receive a lawyer and haven’t, and to hear evidence about whether it is lawful to keep people in jail while awaiting an attorney.

“It’s just crazy that in the year 2023 we’re still asking the Maine judiciary to show us where these people are … and that they’re being lawfully held,” McNamara said.

Jim Billings, the executive director of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services, or MCILS, which coordinates legal representation for the poor in Maine, emailed lawyers on Sept. 29 that he was aware of the “improper appointments.”

“It has been brought to my attention that some courts are making assignments to attorneys who are not eligible for a particular case type or are not on the active roster in that court but are just rostered in another part of the state. I sympathize with the stress and frustration this causes for attorneys,” Billings wrote.

Billings wrote that he told the courts that only attorneys MCILS deemed eligible for a case type could be assigned to cases.

“I have stressed that improper appointments will cause more attorneys to leave the rosters and further exacerbate the crisis we are experiencing,” Billings wrote.

At the same time, settlement talks are set to resume between the ACLU of Maine and MCILS about how to ensure that low-income defendants have competent, trained and supervised lawyers to defend them in court. The ACLU of Maine filed the class action lawsuit against MCILS in March 2022.

The ACLU lawsuit is separate from the petition recently filed with the state Supreme Court.

Ruffner and McNamara said the court system — which faces a backlog of hundreds of cases — has immediate problems, including an inability to provide lawyers to people in jail awaiting trial, that might not be solved by any agreement that emerges from the talks between the ACLU and the state.

They point to a recent order by a federal judge in Oregon that defendants there be released from a county jail if they had their first court appearance and were not assigned an attorney within 10 days.

“Nothing in the proposed settlement touched on this particular issue,” said Ruffner, who attended a Sept. 29 hearing about the class action during which the ACLU and MCILS agreed to restart negotiations.

The filing of the petition with the state Supreme Court and a justice’s recent comments about the risk of an actual denial of counsel in the ACLU class action was coincidental timing, said McNamara in an interview on Sept. 29.

“Regardless of what’s likely to shake out in that case, those are systemic, medium- to long-term things that require funding and the good-will negotiations with the Legislature,” McNamara said. “In the meanwhile, I’m concerned about what happens today and tomorrow and next week with these individuals when there’s no lawful basis to be locked up.”

ACLU of Maine and state officials restart negotiations

A month of settlement talks will resume as the ACLU of Maine and state officials try to reach an agreement about how to ensure low-income defendants have competent, trained and supervised lawyers.

Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy rejected a proposed settlement agreement three weeks ago, saying it was not “judicially enforceable” and it could “close the courthouse doors” for poor defendants if the state didn’t assign a lawyer to represent them in violation of the Sixth Amendment.

“The court’s analysis was incredibly thorough. She recognized the improvements the settlement would achieve but she had concerns. We’re going to try to address those (issues),” said Zach Heiden, chief counsel for the ACLU of Maine.

On Sept. 29, the attorney general’s office, which is representing MCILS in the case, informed the justice that both sides agreed to “engage in negotiations in order to address the court’s concerns” for 30 days with a judicial officer assisting with the talks.

“We want to get this done,” Assistant Attorney General Sean Magenis told the court.

No trial date was set. Murphy previously said she wanted to schedule a trial within a year if a settlement could not be reached.

Maine is required by the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to provide a lawyer at the state’s expense to any criminal defendant at risk of going to jail who cannot afford to hire an attorney.

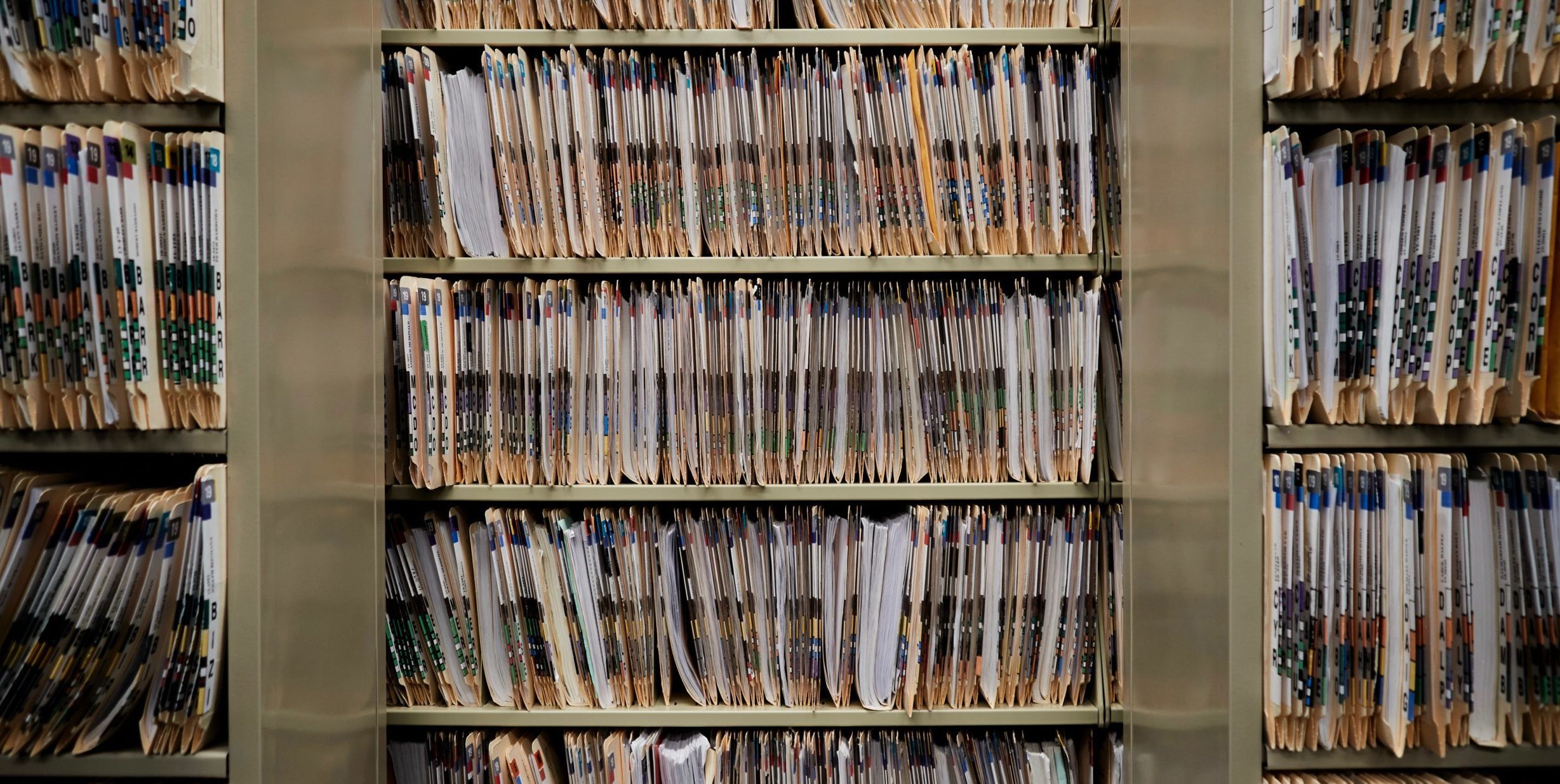

Maine has met its constitutional mandate since 2010 with MCILS, which contracts with private defense attorneys to represent poor clients. During its 13-year existence, MCILS has at times failed to enforce its own rules about attorney eligibility to work on certain case types, and participation by defense lawyers on MCILS’s lists has shrunk significantly in recent years, The Maine Monitor reported.

The ACLU of Maine sued state officials on behalf of impoverished criminal defendants 19 months ago, alleging the state failed to make an effective public defense system, creating an “unreasonable risk” that indigent defendants would be denied their right to a lawyer.

When the class action lawsuit was filed in March 2022, Maine was the only state that did not employ public defenders.

The state hired five rural public defenders late last year, and lawmakers approved money this year to open a public defender office, the Monitor reported.

Mackenzie Deveau, one of the rural defenders, spoke Wednesday about the Sixth Amendment on a panel at the University of Maine School of Law. She said it was “fun but also very stressful” to build the state’s first public defender team while also immediately taking cases.

“We’re a year in now and it feels like we’re just getting off the ground,” Deveau said during the panel. “… Five attorneys are not going to save our state. We really try, we do our best, and we take on what we can, but a lot more is needed.”

At the heart of the lawsuit is the argument that Maine’s public defense system leads to a “constructive” denial of counsel, because the state allegedly does not adequately train or supervise the lawyers it contracts with to represent low-income people.

Murphy has been increasingly vocal about her concern that Maine’s indigent defense system is sliding toward a “constitutional crisis” and the actual denial of lawyers for the state’s poor. Her Sept. 13 order said an unknowable number of defendants may not be assigned a lawyer at all in the next few years.

There is currently an information hole in some counties about how long people are in jail and if they are without counsel, Murphy said Sept. 29 during court.

MCILS is playing a “game of telephone” to obtain information about the status of each case, Magenis told the court. At the end of each day, MCILS doesn’t know who doesn’t have a lawyer without looking at each case, he said.

Leigh Saufley, a retired chief justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court and current dean of the law school, summarized the situation Wednesday.

“There is no question that there is a right to counsel. There are far too many questions regarding the ‘when,’ which is a really critical question, and the ‘how’,” Saufley said.

Supreme Court petition alleges actual denial of counsel

At least one indigent defendant, Angelina Dube Peterson, made her first appearance in court on June 28, and nearly three months later had not been assigned a lawyer, according to a writ of habeas corpus filed with the Maine Supreme Judicial Court.

“An order appointing counsel was issued on June 28, but the space where the name of that counsel was to be written was left blank,” according to the petition.

As first reported by the Portland Press Herald, Ruffner and McNamara filed the petition on Peterson’s behalf and similar defendants on Sept. 20. (Peterson was appointed a lawyer after the petition was filed).

McNamara and Ruffner have accepted court appointments through MCILS for years, although they are working on the petition pro bono.

An appellate public defender office would be able to bring this kind of petition if one existed in Maine, McNamara said.

McNamara said he was disturbed to have to file the petition in the first place. He and Ruffner started to find cases this spring where judges had appointed counsel without saying who the lawyer would be, which is not actually providing a lawyer, McNamara said.

Judges have not been dismissing cases when prosecutors overcharge cases or defendants’ right to a speedy trial are violated, McNamara said.

“The judiciary has neutered itself,” he said. “Whether its speedy trial rights, other mechanisms to dump cases that shouldn’t be brought because of the backlog, and to see time after time again (judges) going against those individuals’ rights just indicates to me that we’re not really interested in identifying what the problems are.”

Barbara Cardone, a spokeswoman for the judicial branch, declined to comment while the petition is before the state Supreme Court.

“Anybody who is involved in the criminal justice system should be embarrassed. I am embarrassed that this happened as a defense attorney, the court should be embarrassed, prosecutors should be embarrassed,” said Amber Tucker, president of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers during the law school panel.

A potential solution is to automatically schedule a defendant to appear in court seven days later if the judge is not immediately able to assign them a lawyer, so the court can keep track of who does not have an attorney, Tucker said.

Maine District Court Judges Sarah Gilbert and Carrie Linthicum are named in the petition, as are unknown judges who oversee cases in the Unified Criminal Docket.

Sheriffs Peter Johnson of Aroostook County and William King of York County — two counties where Peterson was held in jail without a lawyer — are also named.

They all have until Oct. 11 to respond.

Barriers to public defense

Court clerks and judges have struggled for more than a year to find criminal defense attorneys available to accept new cases, the Monitor reported. Defense lawyers say their caseloads are at capacity and they cannot take more cases until the courts clear a backlog of existing cases.

District Court Judge Sarah Churchill refused to let a MCILS-contracted attorney decline a court appointment at the end of September in Lewiston. The lawyer assigned to the case did not usually work in Lewiston, according to court documents reviewed by The Maine Monitor.

Churchill served on the commission that oversees MCILS before Gov. Janet Mills nominated her to the district court, the Monitor reported. Churchill declined to comment.

Lawyers contracted with MCILS are allowed to select courts where they would like to be appointed cases.

A lawyer based in Portland, for example, may choose to be on MCILS’s lists for domestic violence cases in Cumberland County’s courts. That does not mean the attorney is required to accept appointments to domestic violence cases in courts on the midcoast or in Aroostook County.

McNamara said he would stop accepting appointments through MCILS if lawyers continued to be “coerced” to take cases by the courts.

MCILS requires attorneys to have five years of professional and trial experience to be eligible for more difficult cases, such as homicides. The courts made at least 2,000 case assignments to attorneys who lacked the requisite training or experience, an investigation by The Maine Monitor and ProPublica published in 2021 found.

One way to address Maine’s shortage of attorneys is to build capacity and bring more lawyers to Maine that do criminal defense work, said Billings, the MCILS director.

Maine has only one law school. Alyxus Friesen, a second-year law student and one of the panel moderators, says she wants to stay in the state and do indigent defense work, but with few public defender jobs approved by the Legislature there isn’t a direct path into public defense.

Public Service Loan Forgiveness — a federal program that dissolves student loan debt after the first 120 payments for people who work for some nonprofits or the government — is also a major factor for law students thinking about going into indigent defense in Maine, said Jeff Sullivan. He will graduate from the University of Maine School of Law with $130,000 of student loan debt.

“Honestly, loan forgiveness might be the biggest piece,” Sullivan said.

Rowan Hickey said he will graduate with $80,000 of debt because of scholarships and working during college. Hickey said he too wants to go into public defense but it’s “dicey” if he will be able to find a job at a firm that will allow him to do 30 hours a week contracted with the state to qualify for loan forgiveness.

Collectively the three students and some of their peers launched the group “Students for the Sixth Amendment” during their first year at the University of Maine School of Law in Portland. The group hosted the panel Wednesday.

Tristan Dewdney, who co-moderated the panel, is a second-year law student. Public defense internships for students and a shift to a hybrid public defense model in Maine with public defenders and contract lawyers are “ideal,” he said. These changes are on the horizon, but the horizon is still far away, Dewdney said.

“I’m hopeful,” Dewdney said of finding a job in public defense after law school, “but clearly we’re at an inflection point and there’s no certainty.”