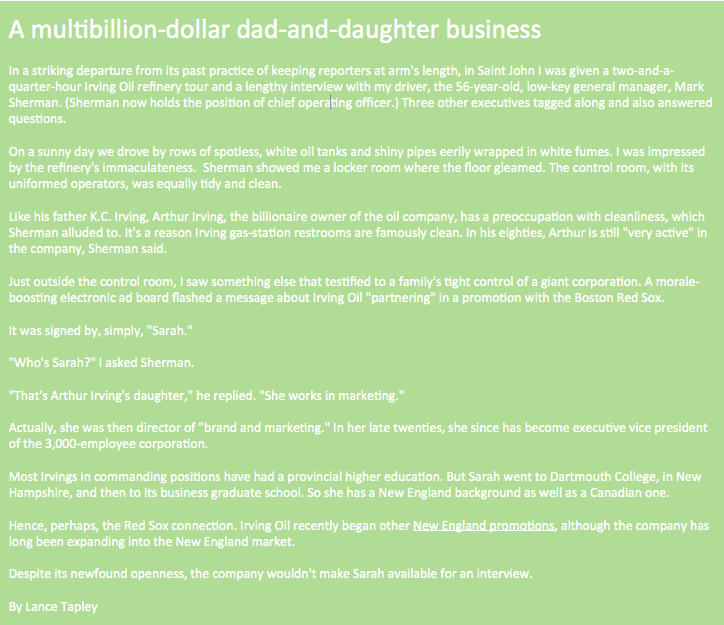

Editor’s note: This is the second story in a three-part series investigating the Irving corporate presence in Maine and New Brunswick and its implications for the state’s future.

SAINT JOHN, NEW BRUNSWICK — If you cruise down the superhighway that crosses this Portland-sized industrial city, you will see Irving everywhere.

That big building rising up in the city center: home office for J.D. Irving’s 15,000 employees.

Go off the highway to grab a coffee at an Irving Oil gas station on Fairville Boulevard and across the street is Kent Building Supplies, a J.D. Irving company with 42 outlets employing 2,800 people in the Maritimes.

Drive a few streets away to look at the picturesque Reversing Falls. Across the tidal rapid is a huge J.D. Irving paper mill.

Head into the historic downtown — known as Uptown — and you’ll pass the offices of Saint John’s daily Telegraph-Journal, flagship of the Irving family’s 20 newspapers in the province, including three daily papers. One French-language daily and seven weekly papers in the province are owned by others.

Those two tankers in Courtenay Bay? Irving Oil. That mammoth refinery not far away with 150 oil tanks. Of course, Irving Oil.

Just outside the city, directly on the Bay of Fundy, is Irving Oil’s supertanker terminal, Canaport, which takes in 100 million barrels a year. Canaport also contains Irving’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) tanker terminal, a joint venture with Repsol, a Spanish company.

If you travel through the rest of the province, you can’t fail to see many of the 1.8 million acres of J.D. Irving forest with their crops of even-aged trees, as well as many of the 2.6 million acres of public or “crown” land the company harvests for its three New Brunswick paper mills and eight sawmills.

Several books and a Canadian-government report have noted that this power over a province by one family is probably unparalleled in the developed world.

“Welcome to an oligarchy,” quipped Gordon Dalzell, greeting a visitor to Saint John. He has spent years 15 years struggling with the Irving companies — successfully — to make the city’s air cleaner as a leader of the city’s Citizens Coalition for Clean Air. The refinery, he said, used to smell “like a match burning.”

In Maine, so far, only Aroostook County comes close to seeing this kind of Irving presence.

“They own the northern part of the state,” said Shelly Mountain, of Presque Isle, referring to J.D. Irving’s influence on the forest economy there. An environmental activist, she’s married to a logger.

But as described in Part 1 of this series, J.D Irving’s recent aggressive lobbying of Maine state government on forestry and mining issues and Irving Oil’s domination of Maine’s wholesale petroleum-products market could suggest the beginnings of a New-Brunswick-like future for the state.

What would that mean? New Brunswick’s Irving critics first point out that Irving domination has not made the province prosperous.

In terms of family income, it’s Canada’s poorest province, according to the federal agency Statistics Canada, which recently reported that New Brunswick’s population of 750,000 is continuing to shrink, attributing the decrease to a lack of jobs. J.D. Irving’s sleek headquarters in Saint John is surrounded by neighborhoods with unpainted houses and crumbling sidewalks.

Whatever the reasons for New Brunswick’s persistent poverty, the undisclosed profits made by the Irving family and its corporations haven’t resulted in a lot of tax receipts to support public services.

That’s because, as several books have documented, the profits generally haven’t stayed in New Brunswick nor even in Canada, but instead have landed in family trusts set up years ago in Bermuda, which has no corporate income tax.

The Bermuda trusts and the Irving empire were largely assembled by the hard-charging business acumen of K.C. Irving, the larger-than-life patriarch who died in 1992. He established the Irving corporate practices that are followed closely to this day.

A central practice is “vertical integration,” when the supply chain is owned wholly or partly by a business, creating tight control over the flow of raw materials, products and prices.

Vertical integration in J.D. Irving’s Maine businesses, for example, means that the company owns woodlands, employs woodcutters and has railroads to transport wood to mills, where the wood is turned into pulp and paper or lumber.

In New Brunswick, vertical integration goes further: J.D. Irving owns specialty wood-product companies producing toilet paper, diapers and other consumer goods. Its newspapers, of course, use newsprint.

This business system has resulted in Forbes magazine estimating that the two K.C. Irving sons, who possess most of the family wealth — James (who controls J.D. Irving) and Arthur (who controls Irving Oil) — are worth $12 billion between them. (That’s in United States dollars. In the rest of this article the dollars cited are Canadian, which has been worth about 75 American cents in recent months.)

Government favors

The Irving companies not only have sent profits offshore, they also are aggressive in securing tax breaks and other governmental financial privileges. They’re tough negotiators with both governments and other businesses.

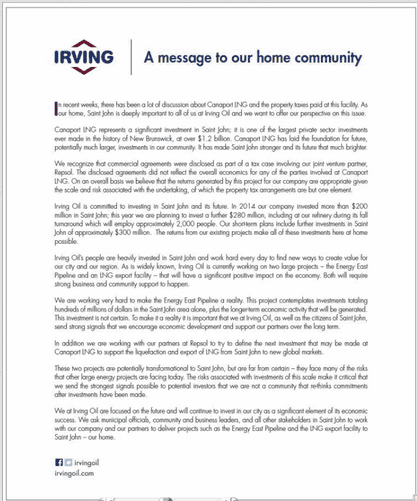

A currently contentious governmental favor to Irving Oil is a limit on the Saint John property taxes paid on the giant Canaport LNG terminal, a limit that had to be agreed to by both city and province.

Canaport has not worked out well for Irving’s partner Repsol, which says it has lost more than $1 billion on its 75-percent share of the investment. The terminal is running at only 20 to 30 percent of capacity.

But Irving Oil is guaranteed at least $20 million a year from Repsol, including lease payments on the property, no matter how poorly the terminal does financially, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News investigation reported, citing court documents.

A few days after Irving signed the lucrative Repsol deal in 2005 — possibly without telling lawmakers about it — the provincial legislative assembly approved the city’s freeze of the LNG property tax at $500,000 a year for 25 years.

The company had said it wouldn’t build the facility unless its taxes were frozen, according to the Saint John mayor at the time, the CBC reported. Based on the property’s $300-million assessment, Irving should be paying $8 million a year.

Saint John’s infrastructure has deteriorated, said economist Rob Moir, of the University of New Brunswick at Saint John, because of deals like this tax freeze. Despite the huge Irving infrastructure within its boundaries, it’s “a city that’s extremely cash-strapped.”

When the Saint John City Council voted to take another look at the Canaport tax freeze, Irving Oil warned the community in an ad in the J.D. Irving Telegraph-Journal that renegotiating the deal might jeopardize future Irving projects benefiting Saint John: The city shouldn’t send signals to potential investors that it’s “a community that rethinks commitments after investments have been made.”

“Irving Oil are very good businessmen,” CBC quoted a Saint John lawyer, “among the best in the world.”

Another Irving business deal is controversial in Saint John. In 2005, J.D. Irving’s Atlantic Wallboard struck a 21-year agreement with a publicly owned coal power plant in the city to be supplied with waste gypsum from the air-pollution scrubbers in the plant’s smokestacks.

If it doesn’t produce enough gypsum, the plant’s owner, provincial utility NB Power, has to pay a fee. So far, CBC News reported, it has paid J.D. Irving more than $12 million.

Irving companies dispense favors, too, such as a free flight for Saint John’s mayor on a J.D. Irving corporate plane, for which he had explaining to do earlier this year. (Similar Irving favors are dispensed in Maine, as described in a Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting story in May about an Irving-paid flight taken by Sen. Thomas Saviello, a Wilton Republican.)

Crown forestry deal

Irving environmental practices are also contentious in New Brunswick, especially J.D. Irving’s treatment of the forests.

Last year, ahead of the provincial legislative election, Conservative Premier David Alward announced a new crown-lands policy including a special deal for J.D. Irving, granting it foresting concessions.

The policy includes a 20-percent increase in the permitted yearly softwood harvest. The Irving deal is for 25 years.

Like the forestry agreement the company signed with Maine’s LePage administration described in Part 1 of this series, the New Brunswick deal was kept secret for a time. The day after it was announced, J.D. Irving promised a $513-million investment in its mills.

But environmentalists and many others were incensed by what they said was the government agreeing to the over-harvesting of the public lands. Hundreds rallied on the Legislative Assembly lawn in Fredericton in protest.

It was “a wildly unpopular decision,” said Green Party legislator David Coon.

Soon after the election, however, the new Liberal premier, Brian Gallant, who had not committed himself to his predecessor’s action, announced his hands were tied by the terms of the contract with Irving.

Tracy Glynn, forest campaign director for the Conservation Council of New Brunswick, commented that both major political parties, the Progressive Conservatives and the Liberals “don’t do anything that doesn’t support J.D. Irving.”

She added: “It’s the culture of fear,” referring to politicians’ fear of a company that employs so many New Brunswickers.

Premier Gallant, his natural resources minister and Saint John’s mayor declined to be interviewed for this article series. And so did J.D. Irving executives.