In the wake of extreme storms that have wrought damage across Maine in recent months, scientists working with the state climate council say the evidence is clearer than ever that unprecedented, accelerating changes are underway.

The council’s scientific subcommittee — which includes researchers working on everything from sea level rise to agriculture to human health — gave a preview on Thursday of the latest findings they plan to contribute to an update of Maine’s climate action plan, due out in December.

“Climate continues to get warmer and wetter, and we are seeing more extremes,” said Maine state climatologist Sean Birkel.

His data showed that Maine’s temperatures, especially lows, have increased by about 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 1800s. It may not seem like much, he said, but it “actually has major implications for natural systems and heat accumulation.”

This warming is changing Maine’s seasonal patterns: “We’re seeing decreasing snowpack, earlier snowmelt in the spring, earlier timing of spring runoff — this is a very early spring this year,” he said.

All 10 of the warmest years on record have happened since the late 1990s. But these extremes cut both ways — Maine saw record dryness during the growing season in 2020 and near-record moisture at that same time in 2023.

Precipitation is on the rise overall and within individual storms. Birkel said more research will be needed to show whether extratropical cyclones — especially sou’easters, like the December storm — are becoming more frequent.

Nuisance flooding is becoming more common, said marine geologist Peter Slovinsky with the state geological survey, and seas off Maine are rising at an accelerating rate.

Scientists are still working to understand a particular spike in sea levels that occurred between 2022 and 2023.

Ecosystem, food and animal impacts

These changes are reshaping marine ecosystems, said Nichole Price of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay — redistributing the food supply of lobsters and changing where they can be caught, or attracting critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to places where they may be less protected from humans.

Warmer summer waters are more conducive to harmful algae blooms and less suited for shellfisheries, she said, while marine heat waves make it harder to grow kelp.

On land, the warming trend is creating new pest problems, but also may open up opportunities for perennial crops, which might now survive milder winters, said Glen Koehler of the University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

“Globally climate change is negative on agriculture, but Maine being a cool state, overall, you would think it would have a beneficial impact — and it may,” he said. “However, so far, it has not. What we see is temperature variability becoming a major issue.”

One example: Warm weather last February and March caused apple trees to bud early, and then a late freeze killed the buds, harming the 2023 apple crop, he said.

Human vulnerability and connection

Public health risks from climate change include more heat-related illnesses, exposure to the elements or carbon monoxide poisoning during disasters, and climate anxiety or disaster trauma, said environmental epidemiologist Rebecca Lincoln with the Maine Center for Disease Control.

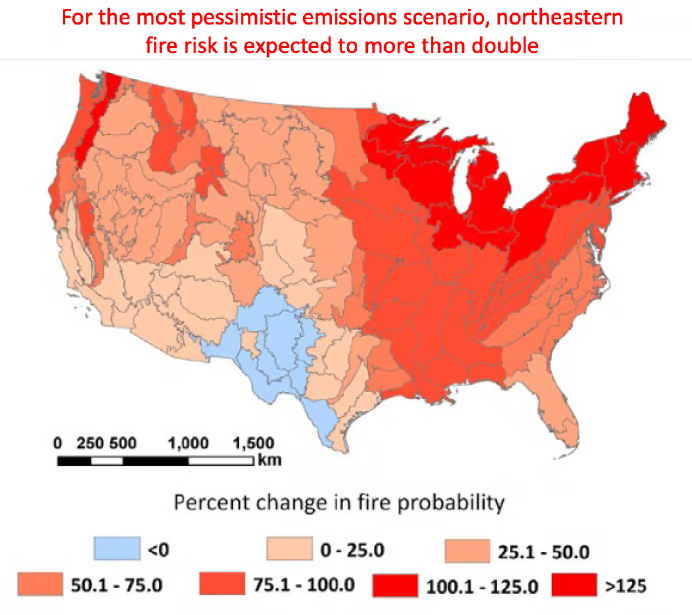

She and Kristen Puryear, an ecologist with the Maine Natural Areas Program, also mentioned wildfires — in terms of smoke drifting over Maine, and actual risk to Maine forests, which Puryear noted are similar in places to those that burned in Nova Scotia last year.

“While Maine’s wildfire risk will remain low compared to the West, it is still vulnerable due to high forest fuel loads, residences located in the forest interface, and limited wildfire-fighting infrastructure,” Puryear said.

Cindy Isenhour, a professor of anthropology and climate change at UMaine, suggested that resilience to climate change will be about community health as much as that of individuals and ecosystems — building social capital and connection, and municipal capacity to collaborate and adapt.

“This idea is really linked to the idea of care across skills, not only care for the climate and ecology, but also for each other, and the work that we need to do … together to solve the climate issue,” she said. “That involves building infrastructures for participatory governance and making sure that everyone has a seat at the table,” she said, mentioning tribal sovereignty as an example.

A need for more forward-looking research

State geologist Stephen Dickson offered a laundry list of data and resources that could help prepare Mainers for future changes, including by aiding farmers in adapting to changing weather patterns and pests, predicting where species and ecosystems will interact in new ways, incorporating indigenous knowledge, and better understanding the impact of flash floods and flash droughts.

Expanded sensor networks, Dickson said, would help the state respond more quickly to toxic algae blooms and other food chain hazards, track stream flows and other parts of the water system more closely, stay alert to threats from sea level rise and erosion, and generally keep the public more informed.

Dixon also identified a range of new data and adaptation needs in the “intervention sector,” on public health, historic preservation, housing, and more.

“We need to project climate migration and tourists, including external drivers. We need to relate back to the demographics that will come as stressors on housing, transportation, the power grid, and economics,” he said. “And we need to really look at the population vulnerability and readiness across the whole state in terms of both the socioeconomics and infrastructure.”

Hope is a framework for action

The climate council’s scientists say they’re adding many more of these “human dimensions” to their forthcoming report. Crucial among those is hope, said the Island Institute’s Susie Arnold.

“It turns out that hope is more than a feeling. Just as we can measure changes in climate variables, scientists also measure hope,” she said. “Hope can be taught, it can be learned and, importantly, it can be restored…. Hope is more than optimism — it’s about taking action. So without the pathways thinking, it’s simply wishful thinking.”

“Pathways thinking” — an awareness of alternatives and the ability to adjust — was one of three components she listed for a constructive kind of hope, a kind that science shows will lead to action rather than anxiety.

This kind of hope requires meaningful goal-setting: “Do you have a plan and a willingness to tweak your plan?”

But Mainers can’t become more resilient and fight climate change in isolation. Human connection, she said, is one of the best predictors of hope.

“An important component to nurture hope is through social outlets, like showing up for presentations in your community, or getting involved with local groups,” she said.

“These also build social capital or strong relationships, which make communities not just more resilient, but better situated for disaster preparedness and response.”

She challenged fellow climate council members to try harder to center hope — stressing solutions, agency and a collective goal — as they spoke to the public about climate change and what, together, they could do about it.