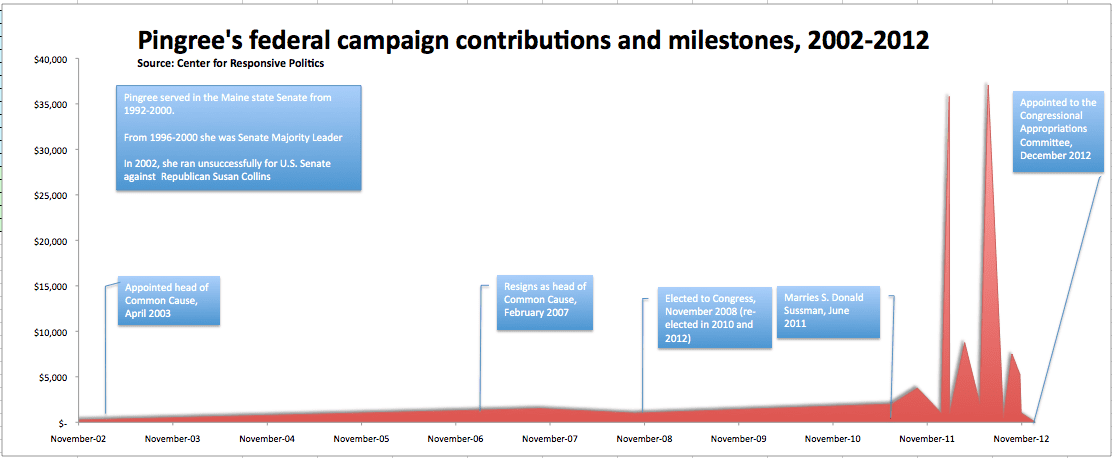

From 1994 to mid-2011, Chellie Pingree’s total contributions to candidates running for national office were $2,950.

But from June 2011 to last November — a period of only 17 months — the Democratic congresswoman from Maine’s first district donated $105,600 to Democratic candidates to Congress and to the party committees that funnel donations to candidates.

That means U.S. Rep. Pingree, who has long criticized the effects of big money and politics, went from giving to fellow politicians at an annual rate of about $180 a year to about $67,000 a year.

“I guess what changed,” Pingree said in a recent interview, “was I got married.”

Before her June 18, 2011 marriage to billionaire financier S. Donald Sussman, she said, “I didn’t have that level of resources to be able to support my colleagues personally.”

Pingree’s newfound wealth allows her to improve her status among her 434 congressional colleagues – especially Democratic leadership – and puts her on a path to become a bigger player in Washington politics, according to political scientists.

Pingree agrees the money enhances her position.

“Members are asked to pay dues,” Pingree said. “The better your committee assignment the more you’re asked to pay in dues. That’s not a secret. That’s just standard.”

In December, Pingree was assigned to the Appropriations Committee – a committee that has traditionally been considered one of the power committees because its members control how federal dollars are spent throughout the country. Getting assigned to this committee is competitive because members are well positioned to channel money into their own districts, political scientists say.

Pingree likened the practice of paying “dues” to her congressional community to being a member in good standing of your local community.

“When the grange has a fundraiser in my town they expect everybody to bring a pie to the bake sale and it’s like kind of your duty,” she said.

Political scientists say that Pingree’s behavior does not make her unique: Candidate-to-candidate contributions have gone up in the past 20 years, according to Bruce Larson, a professor of political science at Gettysburg College and the author of “Congressional Parties, Institutional Ambition, and the Financing of Majority Control.” Lawmakers are now expected to financially prop up their colleagues who are in tight races if they want to gain clout within the party.

“If you want to be a whip, if you want to become a majority leader, if you want to be on a good committee, if you want to be the chair of a good committee, you basically have to do this now,” Larson said.

Known to oppose big money

Pingree, who began her political career in 1992 in the Maine state Senate, sees no contradiction between her six-figure campaign donations and her longtime opposition to the damaging effects of big money in politics.

Before her successful run for Congress in 2008 she was the president of Common Cause, a Washington D.C.-based group that lists campaign finance reform as one of its top priorities. Once in Congress, Pingree helped author the Fair Elections Now Act, which would allow candidates in federal elections to opt into a system of publicly financed campaigns.

“We should take the lessons we learned in Maine to Washington and create a public finance system for Congressional elections that levels the playing field and focuses on small donors,” Pingree said of the Fair Elections Now Act in January 2013. Maine already has an election system that allows candidates to opt for public financing.

The Fair Elections Now Act has never been voted on. Pingree said that in order to pass a national campaign finance reform bill, her party needs more like-minded people in power, hence the contributions to fellow Democrats.

That’s a strategy she said she shares with her husband, who according to the Sunlight Foundation, a non-partisan group in Washington, has given more than $12.21 million in political donations to “campaigns, party committees, ballot initiatives, political nonprofits and super PACs over the years, starting in the 1990s at the federal level and in 2002 in Maine, where he’s spent more than $4.5 million.”

“None of his giving has anything to do with me paying my dues but I do encourage him,” Pingree said.

“He’s just as invested as me in having a Democratic majority in Congress so, in an overall way, he’s anxious to help some of the same people that I help. His giving does not apply in any way to my own effectiveness in Congress,” Pingree said. “The way that it works, you kind of have to do it yourself.”

Pingree met Sussman, who is the majority owner of the Portland Press Herald, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel newspapers, in 2007, her website states. She was elected to Congress the following year and was appointed to the Armed Services Committee and the Rules Committee, then later the Agriculture Committee. She supported the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, the Financial Services Reform Bill and the Affordable Care Act and received high ratings from pro-choice, environmental and labor groups, according to Project Vote Smart.

Pingree served in the Maine Senate from 1992 to 2000 and as Senate majority leader from 1996 to 2000. Her daughter Hannah Pingree represented coastal and island towns in Knox and Hancock Counties in the Maine House of Representatives from 2002 to 2010 and was the Speaker of the House during her last term. Maine’s term limits law prohibited both Pingrees from running for reelection when their terms expired.

Before her career in politics, Pingree founded and ran a knitting business in North Haven. She also served as a tax collector and as a member of the School Board.

Her tenure as president and CEO of Common Cause from 2002 to 2007, after an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Senate, launched her onto the national stage. In that role, she became an advocate of getting big money out of politics.

“The current entrenched pay-to-play system leads to our weak health-care system, as well as weak environmental and consumer protections,” wrote Pingree in an op-ed that she co-authored for The Oregonian newspaper in 2006. “Lawmakers must concentrate on pleasing their donors rather than meeting the needs of their constituents.”

Since her marriage, Pingree has given to 55 federal candidates across the country, including Barack Obama. She gave the legal maximum amount to the Democratic Party by giving $30,800 to both the Democratic National Committee and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

She tended to give to candidates who were in tight races, such as U.S. Rep. Leonard Boswell, D-Iowa, who faced another longtime legislator, Republican Tom Latham, and U.S. Rep. Tammy Duckworth, D-Illinois, an Iraq War veteran who unseated the tea party favorite Joe Walsh. Nearly half of Pingree’s recipients also received contributions from her husband.

‘Everybody’ does it

“It is a conundrum,” Craig Holman, the government affairs lobbyist for Public Citizen, said of Pingree’s large donations and her reputation as anti-big money. “She does believe in trying to get big money out of politics, but she also realizes that she’s in a world where big money dominates politics.”

Opponents of big money in politics fear that large campaign contributions interfere with the democratic process.

Lawrence Lessig, a professor at Harvard Law School, is the author of the recent book, “Republic, Lost: How money corrupts Congress – and a plan to stop it.”

Lawmakers, he suggested in a TED Talk this year, have an almost subconscious trigger that goes off when they are voting on a bill that reminds them to consider how their vote may be seen in the eyes of their donors.

“This dependence upon the funders produces a subtle, understated, camouflaged bending to keep the funders happy,” Lessig said.

Pingree insisted she did not give enough to individual candidates to influence their votes — and influencing them was not her intention.

“I can honestly say there’s never a person who I’ve given a donation to that I’ve gone up to at some point and said, ‘Do you remember I gave you a donation? And now do X,’” she said.

Damon Cann, a professor of politics and methodology at Utah State University, said that members of Congress tend to be more loyal to their colleagues who’ve made contributions to their campaigns.

“The evidence I’ve compiled suggests that leaders in Congress who make contributions to individuals subsequently see those individuals shift their voting behavior towards the leadership,” Cann said.

Pingree is one of four members of the state congressional delegation. Only one other, independent Sen. Angus King, has given personal money to federal campaigns. The Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) lists King as donating $6,000 to the Democratic National Committee and $6,750 to Barack Obama since 2008.

U. S. Rep. Mike Michaud’s leadership PAC, Mill to the Hill PAC, has contributed $162,770 to Democratic candidates in the past 10 years. Republican Sen. Susan Collins’ Dirigo PAC, contributed about $771,000 to Republican candidates in 10 years. Neither legislator contributed any personal money, according to the records.

Politicians often “use their leadership PACs to gain clout among their colleagues and boost their bids for leadership posts or committee chairmanships,” according to the CRP’s website.

Though the money Pingree contributed is her own, it can serve the same purpose as leadership PAC money.

“Those PAC contributions are a little more complicated because a member of Congress has to raise money from a contributor into the PAC,” said Willy Ritch, Pingree’s spokesperson. “And then make the contribution to another candidate, but in the end the goal is the same — getting like-minded people elected to Congress.”

Whether or not Pingree’s behavior interferes with the democratic process, it’s likely that residents of Maine’s first district will reap the benefits of her contributions.

“The more powerful a member of Congress is, the more likely that she or he is able to get things inserted into legislation that benefit her or his constituents,” said Mark Brewer, a professor of political science at the University of Maine. “The more likely they’ll be able to pick up the phone if the executive branch is doing something and say, ‘This isn’t good for my district, can you change something?’”

Brewer sees no problem with mixing money and politics.

“In terms of do I see a conflict of interest, I’d say no,” he said. “As long as we know who’s giving, how much they’re giving and where they’re giving to.”

Then he added, “If you’re going to be out there beating the drum for campaign finance reform, does it seem a little hypocritical? Maybe, but it’s one of those things where everybody does it.”

Disclosure: S. Donald Sussman gave $2,500 to the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting in 2011, prior to his marriage to Pingree.

John Christie contributed to this report.