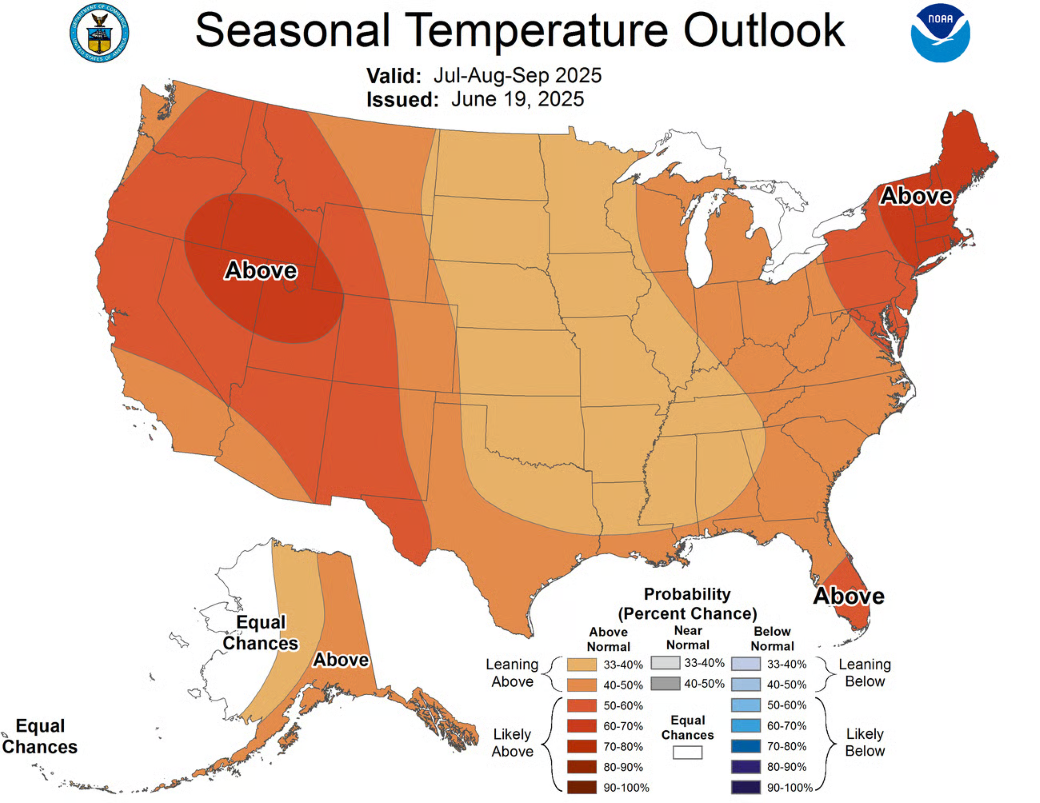

Summer vacation is officially underway, and — while it’s been rainy and cool these past few weeks — the months ahead are gearing up to be hotter than usual, per the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s three-month forecast.

That forecast comes with the potential for more extreme heat, more humidity, and, according to environmental epidemiologist Rebecca Lincoln at Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services, more risk for heat-related illnesses.

Heat can be particularly dangerous in Maine since we are not accustomed to the extreme temperatures seen in other parts of the country, like the West, Lincoln said.

As a result, warmer than usual summer temperatures, especially during the first heat waves of the year, can be stressful for our bodies.

“People are mentally not prepared for the heat — nobody’s got their summer clothes out, nobody’s got their AC in the window,” she said. In Maine, many homes were built to withstand cold, not heat. The same architectural attributes that work to keep heat in during the wintertime make it unbearable in the summertime.

Mainers still use air conditioning at a lower rate than the national average, with just 10 percent having central air conditioning in their homes compared to 67 percent nationally.

But across the U.S., our increasingly A.C.-dependent culture is also a culprit, driving up emissions that cause the very heat we seek to escape. Perhaps indicative of this generational change — and increasing warming — is the fact that Mainers tend to use individual AC units, like the ones that go in the window, with 63 percent installing them each summer compared to the national average of 26 percent.

From personal experience, I can attest to the fact that the AC rarely goes into the window until after that first heat wave produces a glaring reminder that I’ve left an item off my summer to-do list.

I should note here that there’s no technical definition of “heat wave.” The National Weather Service will issue a “heat advisory” when the heat index, a combination of temperature and relative humidity, tops 95 in Maine. A heat warning is issued when that index reaches 105. Heat advisories and warnings vary by region, because, as Lincoln pointed out, heat poses different threats depending on where you live.

Heat can start impacting us when temperatures reach the 80s, and heat-related health impacts curve up as temperatures increase from there. Maine CDC research shows that locally, deaths and emergency department visits increased significantly on days when the heat index was 95 degrees Fahrenheit compared with 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

“A lot of people see the first hot day and say, ‘I’m gonna spend the whole day outside,’” Lincoln said. To avoid overheating and dehydration, Lincoln suggested planning to spend a few hours indoors where there’s access to air conditioners. If there’s no AC at home — or, like me, the window unit hasn’t quite made it into the window yet — Lincoln said air-conditioned stores and libraries or plug-in fans and cold showers are good alternatives.

Though variability may still bring some mild summers, heat extremes are expected to become more common as the climate warms, said Sean Birkel, Maine’s state climatologist and a research assistant professor at the University of Maine. Since the 1950s, average summer temperatures have risen by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit in Portland, Bangor, and Caribou, per observational records in each of those locations.

A trend toward higher overnight low temperatures is one way summer warming is playing out in the state, Birkel said. In Portland, the average number of days where the minimum temperature doesn’t dip below 65 degrees has increased by about 16 days since the 1950s. Across the state, these warm nights come with increased humidity.

“When the air is more humid, that’s when we’ll get the overnight low temperatures that are in the mid- to high 60s, and so it makes for uncomfortable sleeping and our bodies don’t cool off as much,” Birkel said.

Humidity is its own climate feedback loop. Water vapor, the chief ingredient in humid weather, is a greenhouse gas. The more humid the air, the longer heat will linger, trapped under a blanket of steamy conditions with no way to radiate out to space.

On a global scale, carbon dioxide emitted into our atmosphere warms the ocean’s surface, accelerating the rates at which water evaporates. Evaporation contributes more water vapor into the air, which then traps the heat in the global greenhouse and starts the loop again.

Nationally, staffing and funding cuts at NOAA under the Trump administration could impact our ability to observe and prepare for future extremes.

Under President Trump’s proposed 2026 budget, NOAA is set to lose 25 percent of its funding, equivalent to $1.5 billion. That cut would reduce the agency’s workforce, including at the National Weather Service, which former federal employees say will affect the accuracy of weather forecasting and our ability to collect climate data.