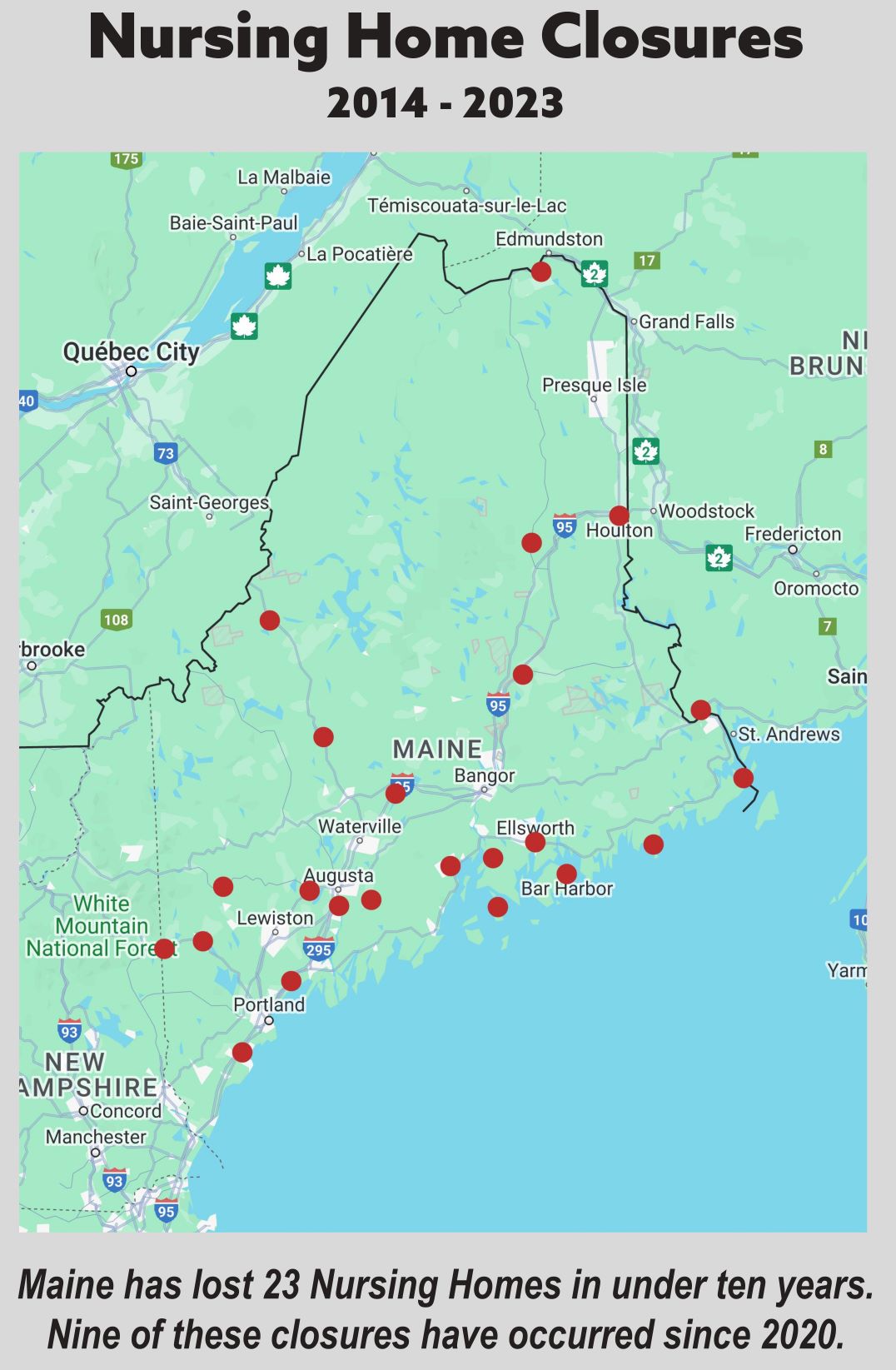

Within the last decade, 23 nursing homes in Maine have closed, prompting long term care advocates, providers and industry leaders Wednesday to urge lawmakers to provide additional funding to prevent more closures.

“This is a call to action to address what has become a crisis in our long term services and support system resulting in the closure of nursing homes and residential care facilities across the state,” Brenda Gallant, the state long term care ombudsman, told a group of lawmakers Wednesday.

Since 1995, Maine’s number of nursing homes have decreased from 132 to 81, according to data presented to lawmakers.

There are currently no nursing homes at all in Hancock County and only one in northern Penobscot County. Half of the homes in Washington County have closed since 2014.

Gallant, whose ombudsman program advocates for long term care residents and their families, said nursing home closures force residents to relocate to other facilities, sometimes much further away.

She told a story about one resident in Aroostook County who could only find a placement in York County, 267 miles away, after her facility closed. The ombudsman program eventually found her a placement in Aroostook County, but only “after great difficulty,” Gallant said.

Nursing homes were the hardest-hit health care sector during the pandemic, said Anglea Cole Westhoff, president and CEO of the Maine Health Care Association, which represents about 200 nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the state. Maine lost 10 to 15% of its long term care workforce, and the primary reason they gave for leaving is stress and burnout.

To keep up with staffing minimums, nursing homes have turned to temporary agency staffing, but the “cost of temporary staff has just exploded and reimbursement doesn’t keep pace with that,” Westhoff said.

Mary Jane Richards, CEO of North Country Associates, which operates 23 nursing homes across Maine and Massachusetts, said their costs related to agency staff increased from about $7 million in 2019 to $39 million in 2022.

“We simply can’t sustain that,” she said.

North Country Associates had eight closures since 2018, including in Bar Harbor, Saco, Belfast, Ellsworth and Houlton, Richards said.

The Department of Health and Human Services is currently looking at reimbursement rate overhaul to adjust how nursing homes are paid for the care they provide, but Westhoff said there has not been any updates on a new model or reimbursement methodology.

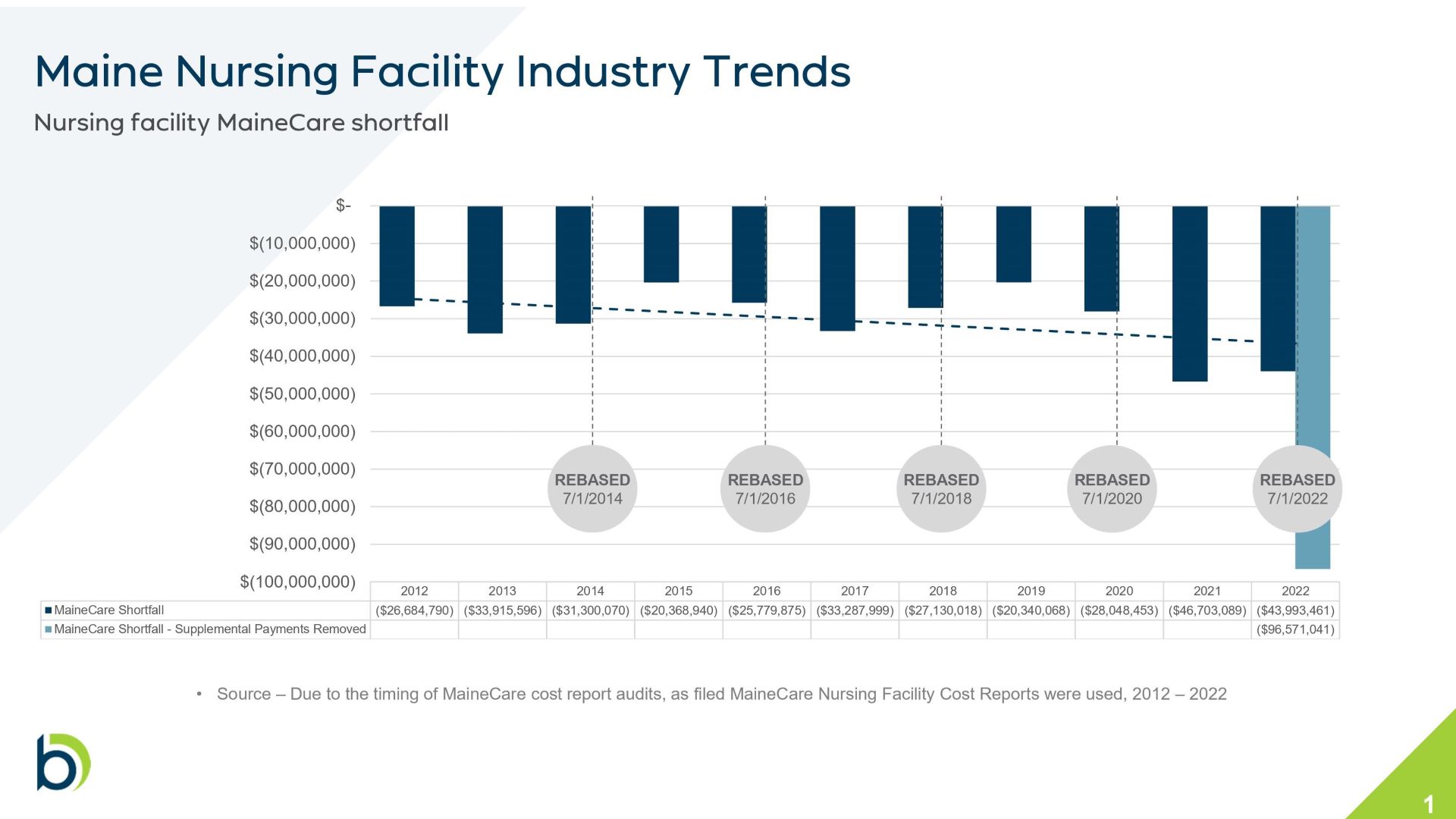

Current MaineCare reimbursement rates fall about $40 short of the cost of care per resident per day, Westhoff said. Since 2012, this annual shortfall in Maine has grown from $28 million to $43 million.

DHHS last month issued $19 million in one-time MaineCare payments to nursing homes for pandemic recovery.

Without these supplemental support payments during the pandemic, the shortfall in 2022 would have been $96.5 million, Westhoff said. Without new investments or continued one-time payments, nursing homes will continue to close, she said.

“The status quo is really unacceptable. More facilities will be left with no alternative but to look at this path of closure or converting to a lower level of care,” Westhoff said. “This is harmful to the resident, to their families and to the communities where they live.”

Sen. Marianne Moore, who sits on the Health and Human Services committee, told The Maine Monitor before the press briefing the best approach to address these challenges is to address workforce shortages by preventing burnout and overtime.

“Throwing money at it is not the answer,” said Moore, R-Washington.

Other solutions the advocates and providers discussed included expanding training programs, supporting family caregivers, expanding adult day centers and providing onsite daycare for direct care workers.

Rep. Anne Perry told the Monitor another key solution is providing a pathway for immigrants to join the workforce earlier.

“This is a long-term problem that’s going to require a long-term solution,” said Perry, D-Calais.

Nursing home beds in Maine have decreased from 10,000 in the mid-1990s to less than 6,400. The disappearance of nursing home beds pushed more Mainers with higher medical needs into less intensive residential care facilities, the Monitor found in a year-long investigation.

“As the state that has the oldest median age, and we are aging, this is a trend that if left unchecked could really spell disaster,” Westhoff said. “As Baby Boomers age, we will not have the capacity to adequately care for older adults who require long term care supports and services.”