Joanne R., 38 years old — “and pushing 60,” she said — has worked since she was 11. She graduated from high school, but didn’t finish college.

“I never really got past the first year — life happens,” she said.

But she has never had trouble getting work. Joanne R., (the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting is not using her real name because she was the victim of domestic violence and fears for her safety) who lives in rural central Maine, has had jobs at summer camps, a country store, a dentist’s office and a jeweler. She’s put in docks, done maintenance and repair work, cleaned homes, painted houses and run a daycare.

She also spent 10 years as a bartender. She sounds like the kind of bartender you wouldn’t mess with, especially when talking about her former boyfriend, the violent and now-incarcerated father of her daughter.

“He’s not going to stay away because I get a protection order on him,” she said. “The only thing that’s going to stop him is a bullet or a bat in the face.”

Joanne R.’s house is a trim and sparsely furnished clapboard New Englander on one of central Maine’s busiest roads. She rents it for $650 a month.

It’s in that house where she’s working the hardest job she’s ever had: single mother to a three-year-old, a whirling dervish of non-stop motion, questions and needs.

“It’s tough,” said Joanne R., leaning back in a chair that’s set in front of the workbench where she makes crafts to sell online. Before she became a mother, she recalled that she “had all the freedom in the world. I could always make money, no matter what. I never had a problem making money.”

“Now it’s a constant struggle every single day. I pray someone will buy” some of her work. “Maybe I’ll find a side job, or I’ll get lucky and something amazing will happen, and I’ll get rich all of a sudden.”

For all of her no-nonsense toughness, being a single mother is taking everything Joanne R’s got. Literally.

“Every week’s the same,” she said. “I’m always broke. The electric, internet, diapers, toiletries, food when we run out of my food card … sometimes, if I have something I can sell … Sometimes I can borrow from my mom or my dad, but it’s not easy to ask.”

Is there anything that’s easy in her life?

“Nope.”

Joanne R.’s descriptions of her life demonstrate what everyone who studies these mothers — scholars, social workers, policy analysts, economists — has concluded: It’s impossible to make it as a single mother working for low wages, as so many single mothers do. Public assistance can help, but it still won’t add up to meet every need.

Economists from M.I.T. have calculated that a single parent supporting one child in Somerset County would have to earn a wage of $21.53 an hour, or an annual income of $44,781, to meet the family’s basic needs for shelter, food, healthcare, childcare and transportation.

That’s not what Joanne R. is making, even if you add up her earnings and the value of the public assistance — food stamps, health care, cash. And it puts her in the same boat as many other single mothers in Maine: Poor and running out of food money by late in the month.

To supplement her meager income, Joanne R. receives food stamps, known as “SNAP” benefits. She gets $507 a month from the federal-state program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (she pays most of her rent with this). She also gets government assistance to help defray heating costs, as well as health coverage for herself and her daughter through MaineCare.

She used to get checks to buy food from WIC, the “Women, Infants and Children Nutrition Program.” Joanne R. said she gave that up after a store cashier held up the WIC check she gave him in front of lots of other shoppers “and hollered to the cashier behind him, ‘What do I do with this?’

“I was completely mortified, I got hot and thought I was going to pass out.”

And the struggle experienced by single parents like Joanne R. is then visited on their children.

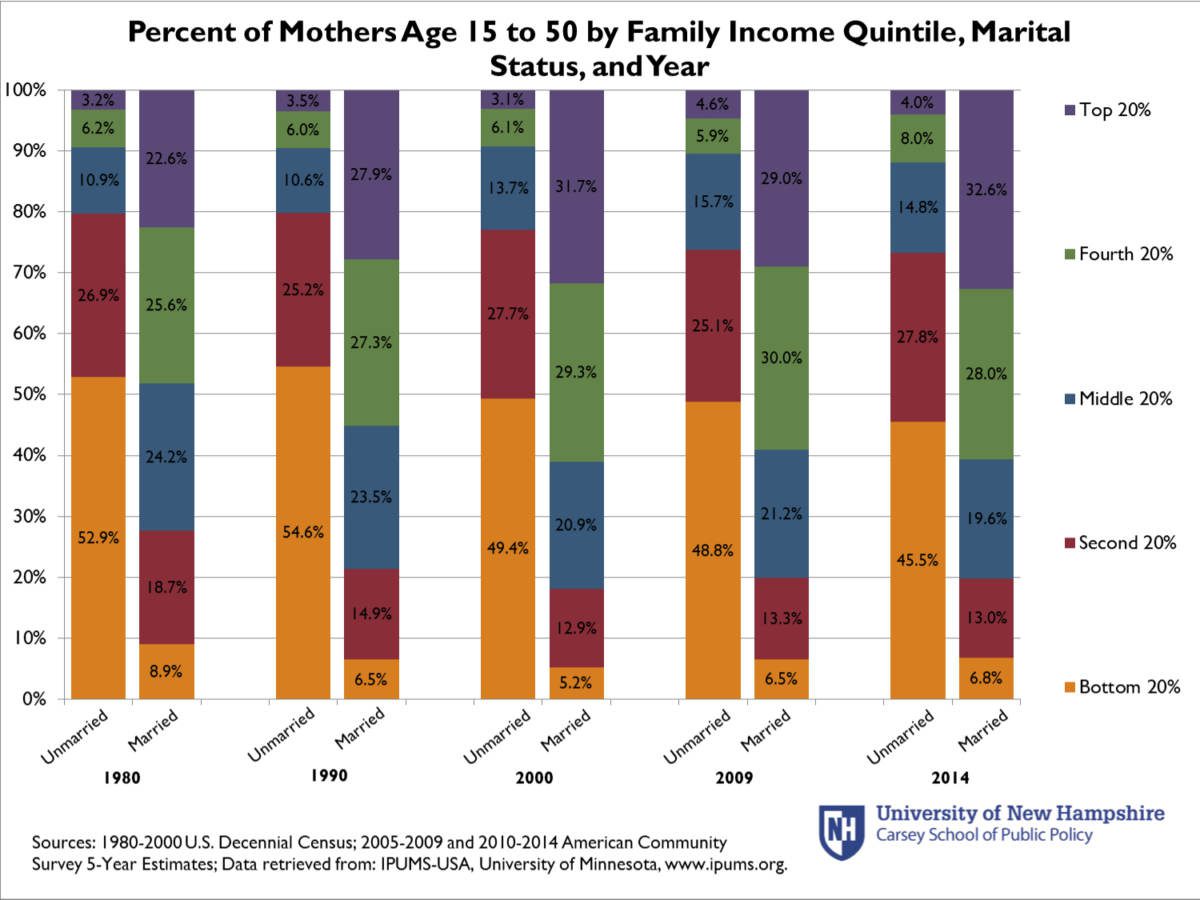

“For children under age 18 in 2014, those living in a mother-only household had the highest rate of poverty (44 percent) and those living in a father-only household had the next highest rate (28 percent),” wrote scholars at the National Center for Education this past spring. “Children living in a married-couple household had the lowest rate of poverty, at 11 percent.”

The road to single motherhood started when Joanne R. got involved with the wrong guy. She met him when he came to visit one of her colleagues at the jeweler where she worked.

“I found out that he was at the Pre-Release Center” in Hallowell, where prisoners did public service work on their way out of the prison system, said Joanne R.. That didn’t raise an alarm for her.

“Well, everybody deserves a second chance,” she said she thought back then.

Now, she said: “No, they don’t. No, they DO NOT.”

She eventually moved in with him and his daughter from a previous relationship.

Things went well for a while. Then, she said, “I found out I was pregnant. We weren’t obviously being very smart, but I wasn’t trying to be either.”

That unplanned pregnancy reflects the statistics about single mothers.

Isabel Sawhill, an economist at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D. C., who has studied and written about single parents, said “Sixty percent of those births to young unmarried women are unplanned, unintended; and amongst the less educated and less well off, it’s much higher than that.”

The pregnancy, said Joanne R., “was not … the most ideal thing to happen. Things started getting really tight money-wise.

“So it just got really stressful around the house. We started arguing a lot … and then when I was nine weeks pregnant, we got into an argument … He was going to leave … I said ‘So that’s just what you do, that’s your M.O., you get someone pregnant and you just leave.’

“It made him freak out, he lunged at me, grabbed me by the throat, slammed me on the bed … told me he was going to kill me.”

“I got him off me. I kept pushing and pushing and pushing. He got off me, punched the fan and broke it, said ‘I wish this was your f…ing head.’”

Joanne R. left, came back, he got violent again and she left — again. The situation was complicated by the fact that she felt responsible for the welfare of her boyfriend’s daughter. She didn’t want to make a police report and risk losing contact with the daughter, but finally did and left him for good. He pleaded guilty to domestic-violence assault, domestic violence criminal threatening and violating conditions of release and is now in prison in Warren.

Looking back, why didn’t she and her boyfriend get married when she found out she was pregnant?

Joanne R.’s answer indicates how normal it has become for women to bear and raise children by themselves: “You anticipate having the baby on your own,” she said. “You don’t expect the father to be there.”

Her ex-boyfriend has five children by four different mothers, according to Joanne R.

Joanne R.’s story fits a pattern with unmarried mothers, fathers and their children who, together, form what are called “fragile families.”

The rise of fragile families “is one of the nation’s most vexing social problems,” wrote scholars in a 2010 Brookings Institution report.

“In the first place, these families suffer high poverty rates and poor child outcomes. Even more problematic, the very groups of Americans who traditionally experience poverty, impaired child development, and poor school achievement have the highest rates of nonmarital parenthood—thus intensifying the disadvantages faced by these families and extending them into the next generation.”

Joanne R.’s doing all she can to give her daughter a stable home and a good start in life, but it takes juggling a million things, she said — and it easily falls apart.

Joanne R. said she gets told weekly — and wrongly — by one agency or another that her benefits are being cut off. She said it takes a good part of her day — time that she could be spending working and earning money — talking to, waiting on hold, emailing or meeting with various government agencies.

“Appease the gods is what I call it,” she said. “It’s like a job.”

Even when and if that all works out, there remains the single greatest problem every single mother has in making ends meet: finding good, reasonably priced child care so they can get and hold a job.

Good child care, if they can find it, is prohibitively expensive for poor and low-income families, unless they can get a government subsidy for it. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy found that poor rural families pay 32 percent of their income for child care — more than five times the percentage of income that middle-class families pay. And families just above the poverty line — defined as low income — pay 18 percent.

The average annual cost for child care for a four-year-old in Maine in 2016 was $6,800, according to the national advocacy group Child Care Aware.

Joanne R.’s mother, who lives nearby, helps take care of her three-year-old while Joanne R. fills orders for her crafts business. The daughter of a friend — another single mother — provides afternoon child care sometimes. Joanne R. spends between $160-$200 per month for child care now, but knows that cost will double, if not triple, once her daughter gets into a preschool program, even if she gets a federal-state subsidy.

“I have no idea how to pay it,” said Joanne R. “I posted online yesterday looking for extra work to do to pay for it.”

But here’s the trap for Joanne R. and many other single mothers: They can only work or go to school to position themselves for better jobs when they have child care. But they don’t have enough money for child care so that they can go to work or back to school. Or else they don’t have a car that can get them to the job that can pay for the childcare.

Joanne R. has a friend at the construction giant Cianbro. “I asked him about their welding training program,” she said, because she thought that would be a path to higher-paid work.

The training and job requirements won’t work for her, it turned out.

“I can’t travel because I don’t have anyone to take care of my child,” she said. “I can’t work nights, can’t work weekends, can’t travel. I can’t even work at Dunkin’ Donuts, because they want you to work overnight.”

Many single mothers go on to have second and third children, sometimes with the father of their first child, sometimes with others. Those unions often don’t last, the fathers pay little or no child support, and the mother and children are plunged further into poverty.

“These women from the outset are more likely to go on through their life and have children with more than one man,” said scholar Cassandra Dorius in a 2011 interview with National Public Radio. “And when you look at their life histories over time, we see that women who have children with more than one man spend about six additional years in poverty than women who have all their children with the same man.

“Men frequently swap families,” continued Dorius. “They give all of their resources, or most of their resources, to the children that they are currently living with. And also, if women go on to have partners with someone new, the man quits paying as much time and money to the first set of children. They get kind of pushed out.”

Joanne R.’s determined to avoid that.

“I have an IUD (intrauterine device, a long-acting reversible contraceptive) and no boyfriend,” she said. “So if I was to ever bring another child into this world — I’m pretty sure that will never happen, and I’m pushing 40 and don’t really want to — I wouldn’t do it without a partner and it being a well-thought-out decision that we both make.

“Nobody’s really saying anything to the fathers at all, you don’t hear about it,” Joanne R. said. “These guys, they take off, they’re violent, they drink, are on drugs, they don’t take care of their kids. It’s all about the mom, what are you doing wrong, why don’t you do this or that? Moms have a full plate … just keeping kids alive is hard enough, let alone all the other stuff.”

But she cautioned other single mothers about having a second, or third or fourth child:

“What are you thinking? Don’t do it! Why? Why?”

She throws her hands up.

“When you’re alone, why, if you can help it, why bring another child into an already stressful life? You don’t even have time for one child, how can you make time for two? If you can’t make enough money for one, not enough money for child care, food, housing enough for one child, how can you make it for two?

“It’s very frustrating to not be able to provide for your own kid, and have to rely on the state, borrowing money from parents, if you even have that option, on the generosity of friends or other family members …”

As Joanne R. speaks, her daughter is downstairs, playing with the babysitter and laughing. She has heard her daughter laughing with the babysitter, laughing when her mother cares for her daughter, laughing while she is a room away trying to make a living for the two of them.

To many parents, the sound of their child’s laughter would bring happiness. But in the life of single mother Joanne R., it brings pain.

There’s “all kinds of stuff they do together,” she said. “I’m jealous.”

“I was supposed to be able to be a stay-at-home mom and be able to do that fun stuff until she went to school,” she said. “But that changed in a matter of seconds.”

Reporting for this story was supported by grants from the Samuel L. Cohen, Hudson and Maine Health Access foundations. Demographic analysis was provided by Andrew Schaefer, Vulnerable Families Research Scientist, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

This is part two of a five-part series. To read more about what went into the reporting of this story, click here.