A black hose from the pump-out truck was snaked across the garage floor, underneath the luxury condominiums at 40 Portland Pier. The elevator shaft had flooded. Again.

A March 10 storm that coincided with above-average tides marked the third time this year that Casco Bay had risen high enough to enter the garage. It was frustrating to Ellie Heath, property manager at Foreside Real Estate Management.

She had sent text alerts and emails to residents a few days earlier, warning them to move their cars ahead of the 11.3-foot predicted high tide.

What she hadn’t figured on was a strong, onshore wind pushing the actual high tide in the harbor to 13.3 feet, according to a nearby government tide gauge.

“Everyone knows to look out for the tides,” she said. “But this one, the surge …”

It wasn’t just the surge, however. The following day was partly sunny. High tide was predicted to be 11.3 feet, but hit 11.8 feet on the gauge, a half-hour after noon.

The water was too deep to walk down the pier in shoes. Some higher-clearance vehicles, such as the pump-out truck, slowly navigated the flooded roadway.

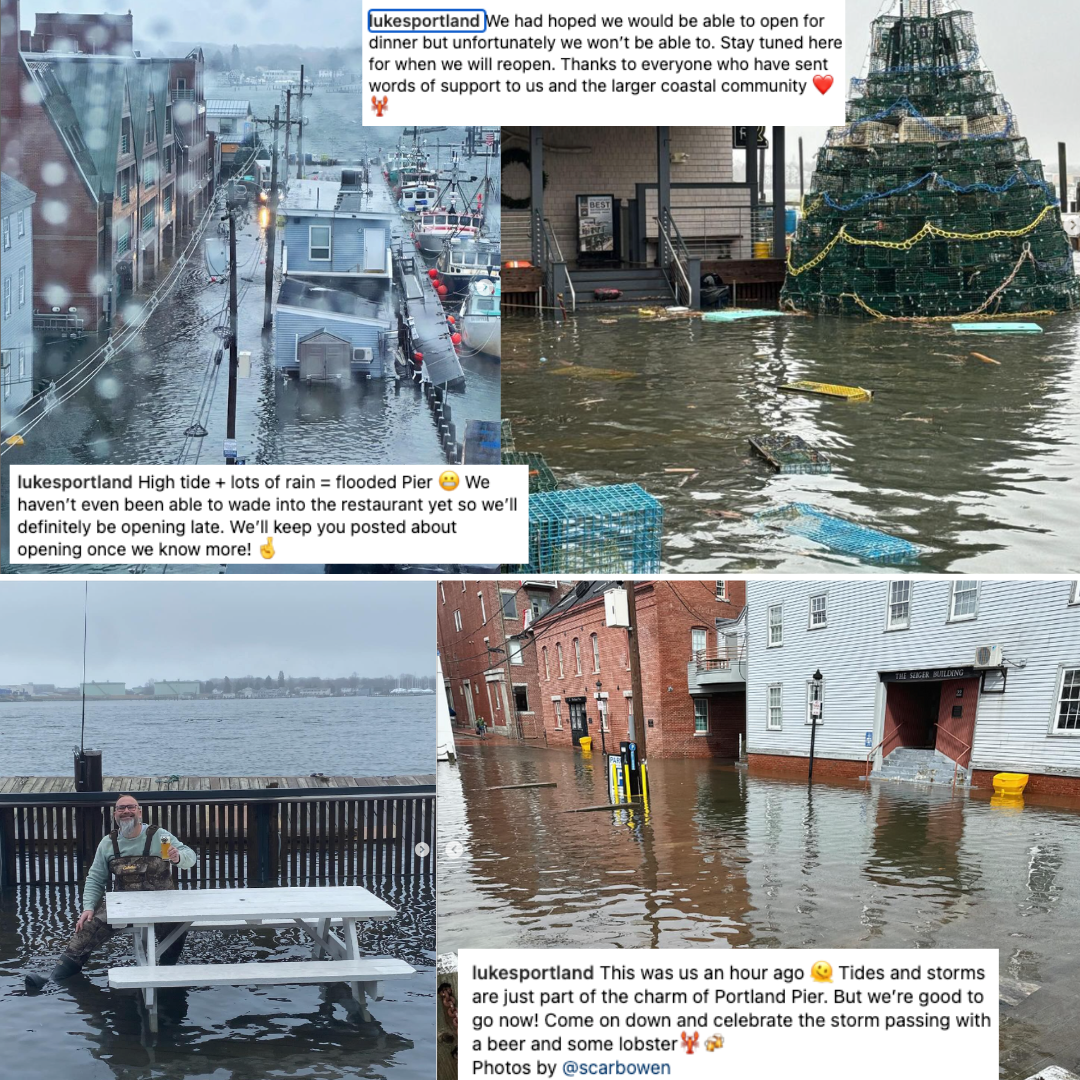

By 1:30 p.m., the water level had fallen enough for foot traffic. That allowed hungry patrons to walk or drive to the end of the pier to Luke’s Lobster, which had been forced to open later in the day on March 10.

“I’m learning about the tides,” said Heath, who was wearing calf-high boots.

Monitoring weather and tides. Moving cars. Wearing boots. Adjusting business hours. Pumping water. Portland Pier offers an early glimpse of how thousands of coastal residents and business owners may have to cope with a rising sea in the years ahead.

Maine has already experienced eight inches of sea-level rise over the last century, according to the Maine Climate Council. Based on projections, that rise is expected to reach an additional 1.5 feet by 2050.

Measures such as raising buildings may be possible, but they are expensive and present technical challenges. Short of that, experts say, coastal Mainers will need to adapt to rising sea levels and — as shown on Portland Pier — learn to accommodate inevitable surges of water in their lives.

Ultimately, one expert said, it may come down to a question immortalized by the British punk rock band, The Clash: Should we stay or should we go?

A microcosm and totaled cars

Portland Pier presents a case study because of its low elevation and diversity of tenants. Jutting 720 feet into the harbor from Commercial Street, the pier is bookended by two popular restaurants. In between are old and newer office buildings, a 36-year-old brick condominium, parking spaces and a lobster fishing fleet.

The lowest point of Portland Pier can start to puddle with a tide just over 11.1 feet, according to the city. It saw water levels above that at some point during four consecutive days, from March 10-13. But only March 10 featured inclement weather. Experts call the other events blue-sky or clear-day flooding.

“It’s kind of a microcosm in a lot of ways,” said Troy Moon, sustainability director for the city of Portland. “It’s a microcosm of what we’re facing in terms of adaptation.”

Portland Pier also is a case study of a rising sea and changing climate.

The pier has experienced occasional flooding for at least a century, but the frequency is accelerating and expected to climb sharply by 2050.

With the help of the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, The Maine Monitor used historical data from NOAA and NASA-funded flood projections from the University of Hawaii to chart worrisome trends.

Planetary cycles cause tides to be larger and smaller year-to-year. That gives the trend line peaks and valleys in annual flooding days, but the NOAA data shows a clear upward direction over time.

Using an 11.3-foot tide as a flood threshold, the pier saw some water only a handful of days in the 1920s and 1930s. Flooding reached 20 days for the first time in 1951 and 30 days in 1976. In 1995, annual flood days hit 32. There were 43 days in 2005, 58 in 2010, 36 in 2020 and 40 last year.

Projections by the University of Hawaii Sea Level Center and NASA indicate that flooding will increase over the next quarter-century. Using an intermediate sea level rise scenario of an additional 3.48 feet in Portland by 2100, there could be 93 flood days in 2030, 104 in 2040, 137 in 2045 and 154 by 2050.

What will that look like for Maine? Forty Portland Pier is a window into a flooded future.

Flooding during the Jan. 13 storm pushed the high tide to a record 14.57 feet. Standing in the condo garage, Heath pointed to where water rose, waist deep, on the wall.

Three parked cars were totaled, she said, because their owners were away and no one could move them. Storage closets also flooded; residents now know not to keep valuables there. The building’s natural gas boilers almost submerged, but had been elevated and stayed dry.

When the tide’s up like that, the pier is kind of an island, Moon said. And there’s not much the city can do to fix it.

“People have to make their own decisions on how to respond,” Moon said. “There’s no easy answer, no short-term solution.”

A wharf without peer

Portland Pier is unique among the 15 central wharfs in Maine’s largest city. The first section is paved and is a city street over filled land. It transitions to wood planks, with a public right of way to the harbor front, flanked by private property and parking.

“It’s a very interesting spot and very complicated,” said Bill Needelman, the city’s waterfront director. “It is a great case study on how devilishly complicated this is going to be.”

Waterfront interests held an informational meeting over the winter with city officials to inquire about remedies, but Needelman said there’s no plan to address flooding.

“Right now,” he said, “the water is making the decisions for us.”

Those decisions involve lower-cost ways to accommodate periodic flooding. It can mean wearing different footwear, finding another place to park, raising critical things like dry goods — learning to live with the water, Needelman said.

“The amount of damage and disruption that properties are going to see depends on their elevation and construction, and their uses,” he said. “A restaurant can survive intermittent disruption to access. But if you can’t get an ambulance to the door of a condo, that’s a problem. We don’t have a solution to that right now.”

“The pier was meant to get wet”

Todd Colpitts was tired of trying to keep water out of the elevator shaft at 50 Portland Pier, the four-story office building next to the condos, so he devised a simple solution. He took a sheet of plastic board, rimmed it with rubber weatherstripping and drilled holes in the elevator shaft trim to attach the board during high-tide storms.

His DIY flood gate kept the sea out of the elevator shaft during the Jan. 13 storm. He drew a line labeled “high water” to show how deep it got in the lobby.

The parking garage and lobby will flood periodically, he said. Trying to keep them dry with sandbags is futile — sandbagging just hurts your back, he said — so it’s best just to keep critical things on the upper floors and plan for flooding on pier level.

When flooding looks likely, Colpitts said, office tenants now plan to work from home. For those who can do it, remote work may be a growing strategy that comes with being on the waterfront.

“The pier was meant to get wet,” he said.

Colpitts is executive vice president of Atlantic National Trust,which owns much of the pier. During a tour in late March, he showed off other adaptation strategies.

It’s not obvious to the casual visitor, but the planking on the private parking spots next to the city’s right of way have been installed with wider spaces between them.

During storms, the sea surge forces water under the pier, but its energy is dissipated through the slats. In contrast, the January storms ripped up sections of the city’s decking, which is nailed closer together. In late March, a barricade marked where a damaged board was recently torn up.

Under the pier during low tide, workers have been installing stout cross bracing to stabilize the wood pilings against the surging sea.

Along a floating dock attached to the pier, a welder has modified the gangway connector that ripped off during one of the storms. It can now ride up and down with enough travel to handle expected surges.

“We know what’s coming,” Colpitts said. “We have to learn to live with it.”

Adapting, accommodating

Along the pier, other inhabitants are doing what they can to adapt.

For instance: Sunday, March 10, was a stormy day marked by astronomical high tides. Rain had stopped around 11 a.m., just 30 minutes before an 11.3-foot predicted tide. But the NOAA tide gauge showed the actual level was almost 13.3 feet. That’s because winds were gusting from the southwest, pushing water onshore.

Public-works crews had set up orange cones blocking off the pier. A worker in a day-glow vest monitored activity. Local TV crews were shooting footage for the evening news. People walking along Commercial Street stopped to take cell-phone photos and videos. An aluminum beer keg floated by. Water was up to the door at J’s Oyster, the iconic seafood restaurant at the head of the pier.

The next day, March 11, high tide occurred at 12:33 p.m. An 11.3-foot high tide was predicted, but the NOAA tide gauge measured nearly 11.8 feet. It was partly cloudy, with high winds gusting from the northwest, pushing water offshore.

It was a classic example of clear-day, nuisance flooding. At 1 p.m., there was still enough water covering the road that people couldn’t walk to the end without boots. Some cars with high clearance and pickup trucks drove slowly, splashing salt water up under their vehicles.

Doug Alofs came out of the Robinson, Kriger and McCallum law firm building, across from J’s Oyster. A partner at the firm, Alofs has worked on the pier since 1997.

Flooding isn’t unusual, he said, but water never came inside the 164-year-old brick building until the Jan. 13 storm. Mostly, he said, coping involves moving cars back and forth from adjacent, low-lying parking areas when a high tide is forecast.

Chris DiMillo is a longtime observer of the trend. His family owns the busy floating restaurant and marina one pier over on Long Wharf. Founder of DiMillo’s Yacht Sales, he has owned an office on the pier since 2015.

Water came up to the office door occasionally. Three years ago the office got wet for the first time. During the Jan. 13 storm, there was standing water in the office.

“So far it happens a couple of times a year,” DiMillo said. “It’s something we deal with on the waterfront.”

More frequent flooding means that Luke’s Lobster patrons should check social media before coming for seafood. Luke’s was built in 2018. It’s raised higher than other structures on the pier, with seven steps into the restaurant and attached lobster pound.

“We’ve been lucky,” said Meaghan Dillion, the company’s vice president for marketing. “We haven’t sustained damage. If we’re going to have any closures, we let our guests know.”

One way to put a positive spin on waterfront flooding is to turn it into an adventure.

On Feb. 14, the Portland Press Herald published a photo of a young woman wearing rubber boots, piggybacking a friend visiting from Florida down the flooded pier, carrying a paper bag. The caption read: “We had to get her a lobster roll.”

The caption didn’t name Luke’s, but local residents can infer the reference. But is it good publicity for a restaurant?

“I don’t think it’s good or bad publicity,” Dillion said. “But if someone goes out of their way to get a Luke’s lobster roll, it’s good.”

In contrast to Luke’s Lobster, J’s Oyster is located in an old building at the head of the pier and susceptible to frequent flooding. The restaurant, which closed in mid-February for winter break, had yet to reopen in early April and attempts to reach the owners or management were unsuccessful. On its Facebook page, J’s posts occasional news about flooding. A photo after the Jan. 14 storm shows the entry door sandbagged against the rising water with a note: “we’re still standing!”

For Gayle Bowness, all these adaptations make Portland Pier a way to study the changing climate in real time.

“I’ve been documenting flooding there since 2015,” she said. “We’re using it as a bit of a living laboratory.”

Bowness, municipal climate action program manager at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, said the historic data and future projections provide good data for making decisions about how to adapt — or not.

“Should we stay here or do we go?” she said.

In time, she said, relocation decisions may come down to necessity. Fishing boats need access to the water. Offices and homes, not so much.

“Are residences essential there?” she said. “It’s a question I don’t want to answer, but it has to be asked.”