Plans to protect thousands of acres of land in western Maine are in jeopardy over a legal question regarding whether the public has a guaranteed right to access the property, the answer to which could result in the loss of millions of dollars in state and federal funding raised by the organization trying to conserve the land.

At a meeting this week, members of the Land for Maine’s Future board were supportive of the projects, which are part of a larger plan, called the Kennebago Headwaters project, to conserve more than 10,000 acres of watershed in Franklin County.

The project includes nearly 1,000 acres of wetlands and the headwaters of the Kennebago River, where thousands of anglers come each year to fish for Eastern Brook Trout and landlocked salmon.

The local conservation group, Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust, was recently granted $1.7 million from LMF toward the purchase of some of the land, which lies just west of Eustis, a small town close to the Sugarloaf ski area and not far from a proposed national wildlife refuge.

But the LMF grants, which are funded by taxpayers, typically come with a requirement that the public have a legal right to access the property, which in this case is not guaranteed, according to an attorney advising LMF.

The LMF grant is just one portion of the funding, but losing it could kill the project, said Dick Spencer, a co-founder of RLHT who now serves as the nonprofit’s attorney, in part because of the timing of the purchase of some of the land, which is set to happen this year.

Spencer said the entire Kennebago Headwaters project will likely cost $11 million. It has the support of Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King, who helped secure $2 million of federal money for the plans last year.

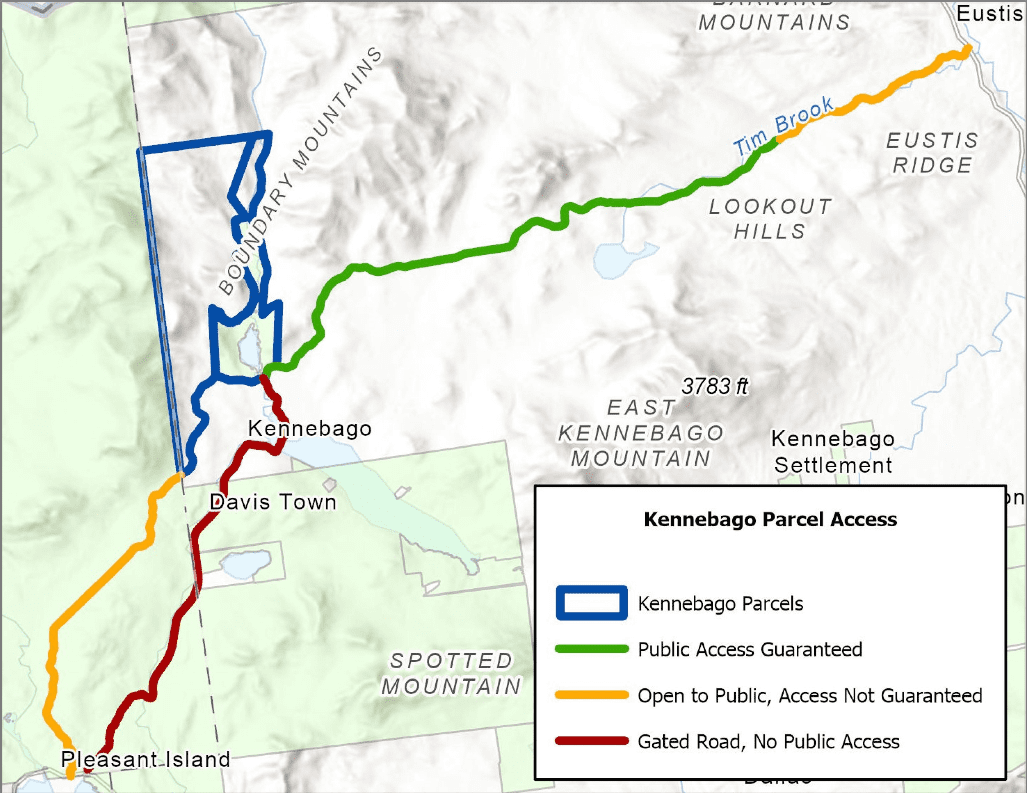

There are three roads leading to the Kennebago project: one, Kennebago River Road, is gated, with no public access. Another, Lincoln Pond Road, is open to the public, but access is not guaranteed. The third road, Tim Pond Road in Eustis, has guaranteed access for the public over all but a small portion. That’s the road Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust is focused on.

“It’s critical, since we’re spending public money, that public access is in there,” said LMF Board Member Catherine Robbins-Halsted. “We want to be careful because this could set a precedent.”

Plans to protect the land from development have been in the works for two decades, but they began in earnest in 2021. Since then, Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust and a private buyer have bought roughly 5,000 acres, and expect to close on an additional 5,000 acres this year.

Trust officials say the possibility that someone would put up a gate or contest the public’s right to access the land is remote at best, and want the state to back up them up in court, should it come to that.

“This is like a law school exam where you try to come up with every possible reason the public can’t go over the road they’ve been going over for the last hundred years,” said Trust Attorney Spencer.

State officials said they want to ensure the public’s investment is protected, and are considering asking the Trust to return the money if public access is ever lost.

But promising to repay nearly $2 million — however unlikely that would be — would be a nonstarter, said Spencer, adding that he would advise the nonprofit’s board to kill the project rather than agree to repay the money.

Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust has a tight budget, operating in most years with a profit margin of a few hundred thousand dollars, according to federal filings. Such an agreement “would have the potential to destroy the trust as an entity,” said Spencer. “You can’t have an unfunded liability on your balance sheet of $2 million when you’re a land trust.”

This is not the first time the LMF board has faced a decision on whether to fund a project that doesn’t have guaranteed public access, said LMF Senior Planner Jason Bulay. And it may become a more common occurrence, as large chunks of land around the state are increasingly being fragmented and sold. (One recent study found the western Maine mountain region lost 12,000 acres to development between 2007 and 2017.)

“It’s a case-by-case decision,” said Bulay.

The Land for Maine’s Future program has been around since 1987, and has helped fund the conservation of more than 600,000 acres of land around the state. The program has a broad mandate that includes preserving public access to sites that are of ecological value as well as those of cultural significance, like working waterfront and farmland and places for people to ski, snowmobile and hunt.

The program relies on local organizations to do the leg work of identifying appropriate places for conservation, getting landowners on board and raising money, but it will contribute up to 50% of the appraised value of a piece of land.

Until this year, money for the projects came largely from bonds or money appropriated in the state budget. But a recent change in law shifts the money to the Land for Maine’s Future Trust Fund, which advocates say will allow the program to have a more consistent funding strategy (it recently went a decade without new appropriations) and raise money from private donors and investments.

Board members said the Kennebago project was “great,” but worried about a “slippery slope” situation and setting a precedent in which public access to an LMF-funded project is not legally guaranteed, even if the possibility of such access being revoked is extremely remote.

Several voiced support for asking Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust to repay the funds if access is lost, although they recognized that would be a “black swan” event for the nonprofit.

The board left the plans hanging on Tuesday, opting to wait for input from the Attorney General’s office before making a decision. They vowed to return to the issue within the next few months.