Shannon Craig-McDaniel used to get recognized when she walked around downtown Lewiston. As a state public health nurse, her clients often remembered her.

“We enter people’s houses so we see them at their best and their worst, and we help however we can,” Craig-McDaniel said. “You learn how to read people and situations.”

In a rural state without county health departments, nurses like Craig-McDaniel serve as the local face of public health for some of the most vulnerable Mainers. They do home visits with expectant moms and new infants, particularly those born with developmental challenges or to parents with substance use disorders. They serve as a trusted voice for health information, a connection to other local resources and a response team for disease outbreaks.

Often their role focuses on education and prevention. But COVID-19 threw them onto the front lines.

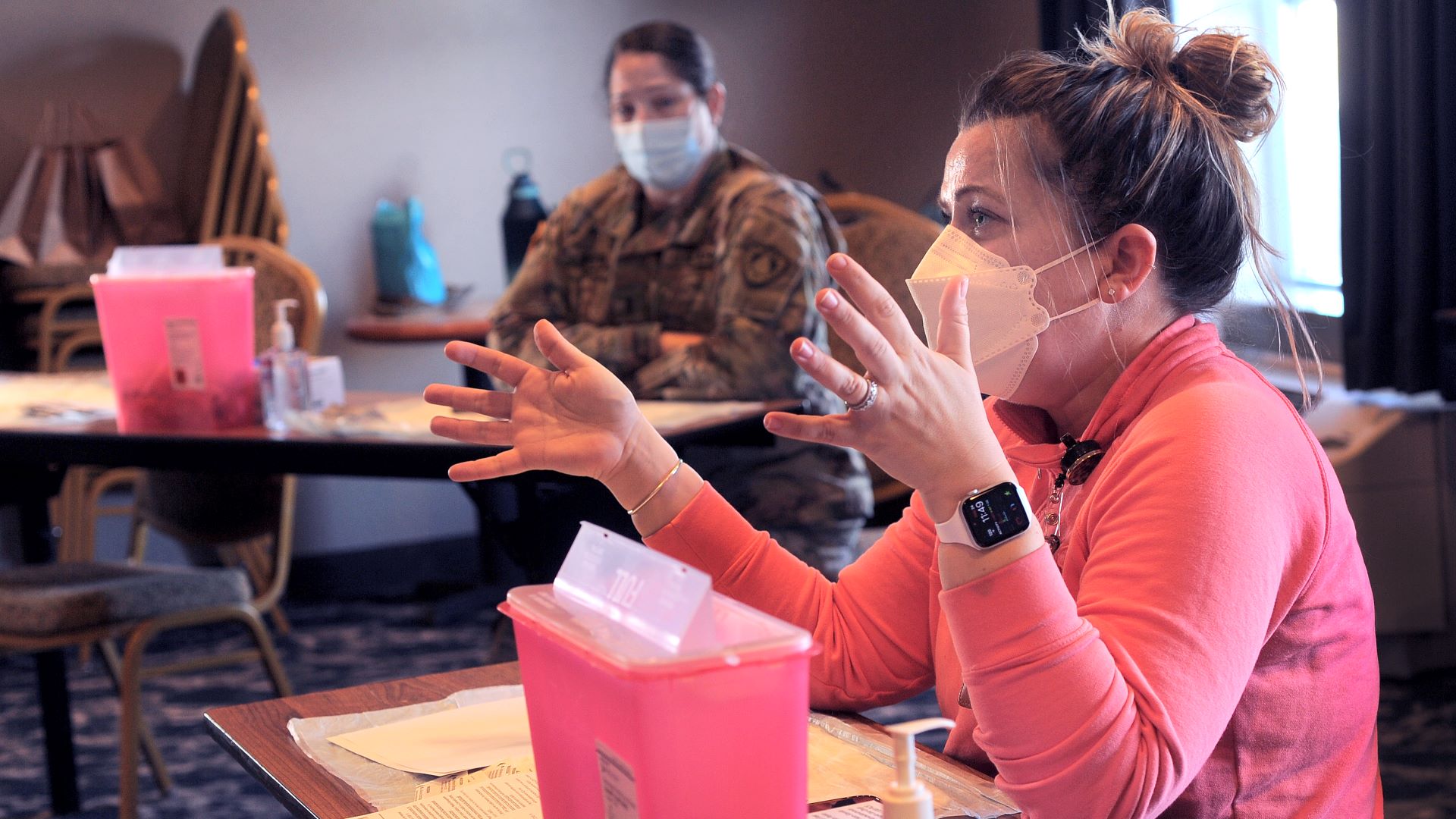

Throughout the pandemic, these nurses helped with testing, contact tracing and vaccination. Craig-McDaniel believes that vaccine acceptance in Maine was higher than in many other states as a result of the relationships and trust that public health nurses built in their communities. Maine consistently has maintained one of the highest vaccination rates in the country.

“It’s been really magnified with a pandemic showing how vital it is to have a public health infrastructure system,” said Jan Morrissette, the former director of Maine’s public health nursing program.

But a review by The Maine Monitor found that the ranks in public health nursing have not fully rebounded years after former Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican, allowed the state-run program to shrink to fewer than 20 nurses at one point.

Public health nurse numbers aren’t much better under Gov. Janet Mills, who faces LePage this year in what promises to be one of the highest-profile gubernatorial elections in the U.S.

As of December 2021, only 31 of the division’s 54 authorized positions were filled. Of those positions, 21 are strictly public health nurses, although program supervisors and educators take on some of the same work as the nurses, according to the state.

Mills, a Democrat, vowed to fill the positions when she took office in 2019. Her administration said it has been actively recruiting, but the pandemic and statewide nursing workforce shortages have made that difficult.

Public health advocates generally agree that the Mills administration has tried to rebuild the nursing program. Still, its proponents are frustrated that the numbers have stalled, especially as the state continues to grapple with a global health crisis.

Maine’s recent high-profile child abuse cases also underscore the need for the prevention and education work public health nurses do with new parents, according to child welfare advocates. Last year, 25 children died due to abuse or neglect — the state’s worst year on record.

Morrissette and others fear a worse future for public health nursing if LePage unseats Mills this November.

In an interview with The Maine Monitor last week, LePage said he will fill all vacant positions and fully fund the program if elected.

Public health nurses are “valuable,” he said, but the program needed more oversight and a reporting structure, which is why he didn’t fill openings while his administration considered reforms.

“I’m a big believer that if you’re going to hire people, they have to be effective and they have to optimize their skill level to help society,” LePage said. “These are public health nurses being paid by the public and the public has a desire to get the proper services.”

Former Sen. Brownie Carson, a Democrat who sued the LePage administration in 2018 for failing to comply with legislation requiring him to fill all vacant positions, said public health nurses are vital to the most vulnerable Mainers.

“This still gets my blood pressure up,” Carson said. “It’s a hugely important subject, and I have been deeply disappointed by what I perceive as a lack of resolve to fully staff the public health nursing service and really make it a vital working part of Maine’s public health infrastructure.”

‘A good trajectory’

Public health nurses have maintained their normal workload even while responding to the pandemic, said Jemma Penberthy, the public health nurse supervisor for Cumberland and York counties.

They continued to work with new moms, new babies and clients with tuberculosis. They reduced home visits when possible and followed COVID-19 safety guidelines when in-person meetings were required.

“Tuberculosis doesn’t stop when there’s COVID,” Penberthy said.

The Division of Public Health Nursing operates under the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Nurses are stationed across the state’s eight geographic health districts.

Public health nurses develop “profound” relationships with clients because they spend more time together and in more intimate settings, Penberthy said. For tuberculosis cases, a nurse watches the client take their treatment every day, sometimes for months.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, public health nurses helped with health assessments and vaccination clinics in 2019 when more than 400 asylum-seekers stayed at the Portland Expo over a summer. The nurses also set up vaccine clinics in 2009 during the H1N1 pandemic and responded to an hepatitis A outbreak at a Portland homeless shelter.

Earlier this year, a COVID-19 vaccine clinic at the Augusta Armory overseen by public health nurses and state partners administered nearly 11,000 shots, according to the Maine CDC.

Despite the unfilled positions, Penberthy said the public health nursing program is growing in the right direction.

“I see the trajectory being a really good trajectory, though it might seem slow to the outsider,” said Penberthy, who has been with the program for more than four years.

Multiple public health nurses and experts told The Maine Monitor that their role in preventing health problems is underappreciated and hard to quantify.

But low-income Mainers who depend on their services are more likely to recognize what public health does, said Josie Ellis, a supervisor for three districts along the coast and central Maine.

“Our homeless patients (know) what public health does,” Ellis said. “People who are more economically advantaged … might not have as many opportunities to interact with or require the assistance of public health, and so they might not be as familiar.”

While Maine needs more public health nurses, Ellis said in her three years serving the state, she’s never seen a referral or request for help get declined.

Nurses worked nights and weekends to maintain services during the pandemic, she said. They were “overjoyed” and emotional when they learned of the vaccine. A year later, Ellis still is running COVID-19 vaccine clinics, including a recent one in Thomaston.

“I know for a fact that a direct result of those clinics was lives being saved,” she said.

Support for most vulnerable

Joanne Joy, who has worked in public health since the late 1990s, said nurses like Penberthy help address health challenges that disproportionately impact low-income Mainers. They often are connected to public health nurses based on prioritized needs, such as premature births.

Wealthier parents may already have access to a primary care provider and not need resources from a public health nurse, said Joy, who serves as senior program manager of prevention for Healthy Communities of the Capital Area.

Low-income Mainers are more likely to have chronic health conditions that afflict their infants, Joy added. For example, people who live below the poverty line have higher rates of smoking than the general population. And smoking is associated with premature births.

“So that connection between public health nurses, low weight or early infants, and tobacco is a strong connection,” Joy said.

Home visits from public health nurses are an opportunity to address child developmental challenges and prevent child abuse or neglect, said Melissa Hackett, policy associate with the Maine Children’s Alliance. These visits carry less fear and stigma than a visit from a child protective caseworker might.

In the wake of recent high-profile child abuse cases, discussion centered on what went wrong “downstream,” once families already are in the child protective system, Hackett said. There should be more focus on the type of prevention work public health nurses do to help parents manage challenges before there is abuse and neglect.

Most child-abuse cases involve children under age 3, Hackett said. Infants are more fragile and create a stressful environment for new parents.

Maine aspires to universal home visits for all new parents, but doesn’t have the capacity to achieve that goal — no state does, Hackett said.

In addition, COVID-19 pulled public health nurses into the state’s emergency response at a time when the unfilled positions meant nurses already were stretched thin.

“(The pandemic) serves as a reminder that if we’re not at capacity, that really does pull away from other really important things like a prevention of child abuse and neglect,” Hackett said.

By the numbers: Mills, LePage

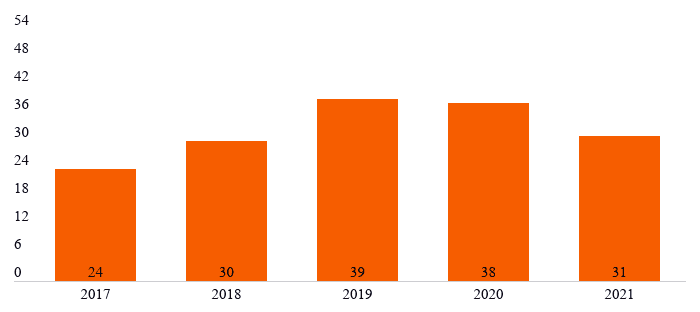

Prior to LePage taking office in 2011, Maine had 50 public health nurses. By 2016 there were 25, an investigation by the Bangor Daily News found that year. In response to the news report, Maine lawmakers passed legislation requiring the program to be fully staffed.

LePage vetoed the bill in 2017, citing deficiencies in the program, which he argued wouldn’t improve with more nurses. He said the program was “ineffective” and nurses were performing duties that should be handled by community care workers or social workers. LePage added that public health nurses made, on average, two visits a week, which he said was below the national standard of five visits a day.

Lawmakers overrode LePage’s veto and the law went into effect.

Carson sued the LePage administration in 2018 for not following the law and filling the vacant positions. When Mills was elected, Carson’s lawsuit was carried over under the new administration. A judge ended the lawsuit in 2019 after finding that Mills was “substantially complying” with the law.

By the end of that year, 39 of the 54 positions were filled, according to Maine CDC records.

The numbers dipped back down to 31 filled positions by the end of last year.

“The governor deeply values public health nurses and the critical role they play in protecting the health of Maine people, especially throughout the pandemic, which is why since day one we have tried to bolster the ranks of Maine’s public health nurses — consistent with a directive from the state legislature,” said Lindsay Crete, spokeswoman for Mills.

The Mills administration said it has actively recruited nurses for the public health nursing division and dedicated $1.5 million in federal COVID-19 relief funds to attract young people to healthcare professions as a way to address the statewide nurse shortage.

“The governor is grateful to Maine’s public health nurses, and she will continue to do all she can to fill these critical positions,” Crete said.

Since taking office, the Mills administration has hired 27 new staff and promoted eight others in the public health nursing program, Maine CDC spokesman Robert Long said.

Recruitment efforts include radio and digital advertising, as well as open houses for prospective candidates, Long said. Positions have been posted widely, including on the Bureau of Human Resources website and in the American Nurses Association Journal.

The Maine CDC is considering incentives to new nursing graduates and providing an extensive orientation for new hires. And the Mills administration allocated part of a federal workforce grant to educational programs and Maine’s two municipal health departments in Bangor and Portland.

Morrissette, who was a public health nurse in Maine for 16 years before becoming the program director in 2005, said it’s been “disheartening” to see the ranks of nurses stagnating, despite the legislation passed years ago. But she’s sympathetic to challenges related to the pandemic.

“We had eight years of devastation (under LePage), and it takes a while to build back,” Morrissette said.

LePage shot back in his recent interview with The Maine Monitor, saying the current administration had 15 months between taking office and the start of the pandemic to fill all vacant positions. But in March 2020, the state employed 38 people in the program, including 24 frontline nurses.

LePage said he supports programs that help people help themselves. He wants to eradicate poverty, domestic violence and opioid addiction. But that won’t happen by “giving them everything and letting them go to their own devices.” Rather, it’s important to teach by example, he said.

Public health nurses play an important role in outreach to Mainers struggling with those challenges, particularly babies born addicted to opioids, he said.

But he questioned whether having more public health nurses would have aided the state’s response to COVID-19. They could have helped with outreach, particularly in rural Maine, LePage said, but he argued that most Mainers received testing and vaccinations from hospitals, clinics and pharmacies.

As governor, LePage said he would make sure the public health nursing program is “alive, well-funded, and that the people are trained and we have accountability.” That means better defining their duties, implementing a data reporting system and increasing expectations for the number of visits.

Despite frustration with the slow recovery under Mills, public health experts like Morrissette worry it could be worse if LePage wins re-election. Morrissette, who stayed in the LePage administration for a year, said she watched her former program “bottom out” under LePage.

“No matter what the spin has been, he is still Paul LePage,” Morrissette said. “He does not appreciate programs that help the most needy in the state.”

A ‘patchwork’ system

When she began her career in early childhood disability services four decades ago, Sue Mackey Andrews said five public health nurses served her community in the Dover-Foxcroft area. Now her community has one.

A second public health nurse in the area is contracted with Bangor Public Health.

Mackey Andrews praised the two nurses and said they are very responsive to the community’s needs. But nurses were stretched thin even before the pandemic.

“You’re not going to have an effective public health system without public health nursing,” she said. “But if it’s continued to be understaffed, then it’s not going to be able to be as effective as it could be.”

The state doesn’t have a visible public health presence in Dover-Foxcroft and Piscataquis County often feels like the “forgotten county,” Mackey Andrews said. During the pandemic, her community formed a volunteer COVID-19 task force to fill gaps in services on the ground. The group continues to meet and has plans to tackle other public health challenges going forward.

The state’s current public health system is a patchwork of state programs, councils and local organizations, said Morrissette, the nursing program’s former director. The needs vary across the state so the system is always adjusting.

“Right now we just need more,” Morrissette said. “We need more in that patchwork to be able to provide the services that are needed.”