In the Downeast town of Machias, there’s a new program bringing hope to single mothers caught in poverty.

The program helps those mothers go to college. And Monique Morin, 21, can’t stop smiling when she tells people about it.

“I never in a million years thought I was going to be in college,” she said. “Not even a little bit.”

But hope is in short supply for many single mothers who are striving to feed their children, pay their bills, get an education or find and keep a good job.

And without hope, without a belief in a better future for themselves, they are likely to have more children and never break the cycle of poverty for themselves or their kids.

Postponing having children you are unprepared to raise requires “having enough hope and optimism about the future to make it worth deferring childbearing, doing more planning, not having casual sex with just anybody, planning your parenthood because you have a bright future in mind,” said Isabel Sawhill, one of the country’s leading experts on single-parent families.

Policy experts and advocates for the poor are trying to find solutions. Those solutions, said Sawhill, a Brookings Institution economist, must address both generations caught in the crisis: the parents and their children.

For the single mothers, said Sawhill, there will have to be additional public spending that helps them and their children climb out of poverty. She also advocates for free access to effective, long-term contraception that will help them avoid future pregnancies.

“We can afford it,” she wrote in her 2014 book, “Generation Unbound: Drifting into Sex and Parenthood Without Marriage. “That said, more money just can’t be the whole answer. There is not enough money to create adequate supports for the growing number of ‘fragile families.’”

The marriage “genie is out of the bottle,” she said, adding that she doesn’t expect Americans to return to the institution of marriage in the numbers of the past. But reducing the number of children born to unmarried parents who are unprepared and unable to take responsibility for them is one of her major goals. (Seventy percent of all pregnancies to single women under 30 are unplanned, according to a Brookings 2014 report co-authored by Sawhill.)

One solution is something known as LARCs: long-action reversible contraceptives, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs). They are, Sawhill said, a “highly effective way to reduce unplanned or unwanted pregnancies.”

By postponing childbearing, writes Sawhill, mothers and fathers can better prepare themselves — with education and job training — to provide a stable, supportive home for their children.

There is no comprehensive data on the percentage of women in individual states — including Maine — who are currently using these types of contraceptives. Nationally, however, from 2002 to 2012, the percentage of U.S. females aged 15–44 using them increased from 2.4% to 11.6%, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which conducts policy research on reproductive rights.

Long-action contraceptives are not cheap. According to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, “the medical exam, the implant or IUD itself, insertion of the device, and follow-up visits can range from $500-$1,000.” They can last for several years.

Staff at the Portland office of Planned Parenthood said that a bill passed during the last legislative session will give free access to these and other contraceptives to 36,000 low-income Maine women through Mainecare and at health clinics.

The bill has yet to be implemented.

“We are working on the adoption of the rule and we have an anticipated effective date that will be retroactive to October 1st,” said Sarah Grant, director of communications with the Office of MaineCare Services, in mid-October.

“We certainly plan to initiate an awareness campaign once it’s implemented,” said Nicole Clegg, director of public affairs in Maine for Planned Parenthood of Northern New England.

Clegg testified to legislators: “It should be no surprise then that unintended pregnancy contributes significantly to the cycle of poverty many Maine women are struggling to escape.” She added that “study after study” shows that women who give birth to children they did not plan on having “are more likely to fall into poverty, unable to support themselves financially and require public assistance for their family …”

Promoting the wider use of more effective birth control isn’t the only way the problem is being addressed. Experts also agree that poor single parents — and men and women who may be headed that way — also need to feel they have a future.

Creating hope and optimism is the focus of several efforts that aim to help move Maine’s single mothers out of poverty and make sure that their children, once grown, don’t move back into it.

Child care: ‘huge issue’

If there’s one idea on which there is unanimity, it’s that poor and low-income families such as those headed by single parents need high-quality, affordable child care so that the children can thrive and their parents can have steady work or go to school.

“Child care is a huge issue,” said single mother Joanne R., who lives with her 3-year-old daughter in central Maine. Like many other single mothers interviewed across the state, Joanne R. (her name is being withheld because she was a victim of domestic abuse and fears for her safety) said that high-quality, low-cost child care for her daughter would be the single biggest element in helping her get on her feet financially.

“Good child care,” said Joanne R. “is extremely important and really overpriced and hard to find.”

Joanne R. knows firsthand what researchers at the child care advocacy group, Child Care Aware, determined in their study, “Parents and the High Cost of Childcare: 2015”: “In Maine, a single parent with two children pays 73% of their income towards child care. A married family at the poverty line with two children pays 68% of their income towards center-based child care. Annual cost of child care for an infant and a 4-year-old is $16,381 which exceeds the cost of the state’s four-year public college tuition.”

U.S. Sen. Angus King, an independent who served two terms as Maine governor, introduced several bipartisan pieces of legislation this summer to deal with the problem of families in poverty. Those pieces of legislation are awaiting Senate committee consideration.

“How do we get out of this trap?” asked King. “If you’re a single mom you can’t do education or work if the child care cost is way more than you’re making.”

So one of King’s proposals would transform the federal child care tax credit.

“The current credit is a good thing but that only benefits the middle class,” said King. “If you’re low income and have no tax liability it doesn’t help you at all. The very people you want to help the most, it has no value.”

King’s bill turns the tax credit into cash for poor parents.

Another King-sponsored bill would change how the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, or TANF, works. The federal-state program requires recipients to work or go to school (high school or post-graduate programs), but cuts off benefits (such as a child care subsidy) after one year. King’s bill would allow recipients to go to school for up to three years and still receive those benefits.

“What I’m trying to do is modernize the program to take cognizance of the current reality that it takes more education to get a decent job than it used to,” said King. “We can’t arbitrarily say that it takes 12 months, and that’s what you get.”

Learning to learn

“Dr. Lori” — that’s Professor H. Lori Schnieders, assistant professor of psychology — plants herself in front of a group of animated young women in a classroom at the University of Maine at Machias. Her students — all women, all single mothers — have just arrived after having supper with their children provided at a university child care center. On their way in the door, they pick up snacks — tangerines, popcorn, puffed vegetable sticks, bottles of water.

If there’s another idea on which there’s unanimity, it’s that most single mothers in poverty can’t get out of that poverty without more education or job training.

But it’s hard to go to college when you’ve got two kids and a low-paying job with erratic hours and a car that breaks down all the time and no self-confidence about your ability to handle college coursework.

This new program in Washington County, called “Family Futures Downeast,” aims to knock down every obstacle so that these single mothers can get a college education and career training and pull their families out of poverty.

Knocking down those obstacles can mean doing the most mundane, but essential, things: The program provides gas cards so the mothers can get to class. Classes are scheduled in the evening so the mothers can work during the day. High-quality child care is supplied while parents are in class. The cost of tuition, books, supplies, even computers is covered. And each woman is assigned a mentor, who can provide emotional support, help her set goals and keep to them and help negotiate the many logistics of what it means to be poor, a parent and a student, all at the same time.

Her students “run the gamut,” Schnieders said, “from the young mom who has had some substance issues … who is working really hard and trying very hard to turn her life around, to a couple more mature moms, one with four children who truly understands the worth of the degree and how that’s going to make a difference in her children’s lives.”

There’s also, she said, “a newly single mom, within the last few weeks, whose not-married partner just left and she’s being supported by (her classmates) through the breakup and a rough time, to a couple that are pretty savvy.

“In the section that I have them in,” she said, “they’re … learning to learn, understanding learning style, how to negotiate with a professor if you’re having problems.”

In other words: How to be a student.

Then there are the skills she teaches to help them run their complex lives: “Time management, money management, sleep hygiene. The personal growth part is: How do I become part of the communities that I’m in and not stay on the fringe,” said Schnieders.

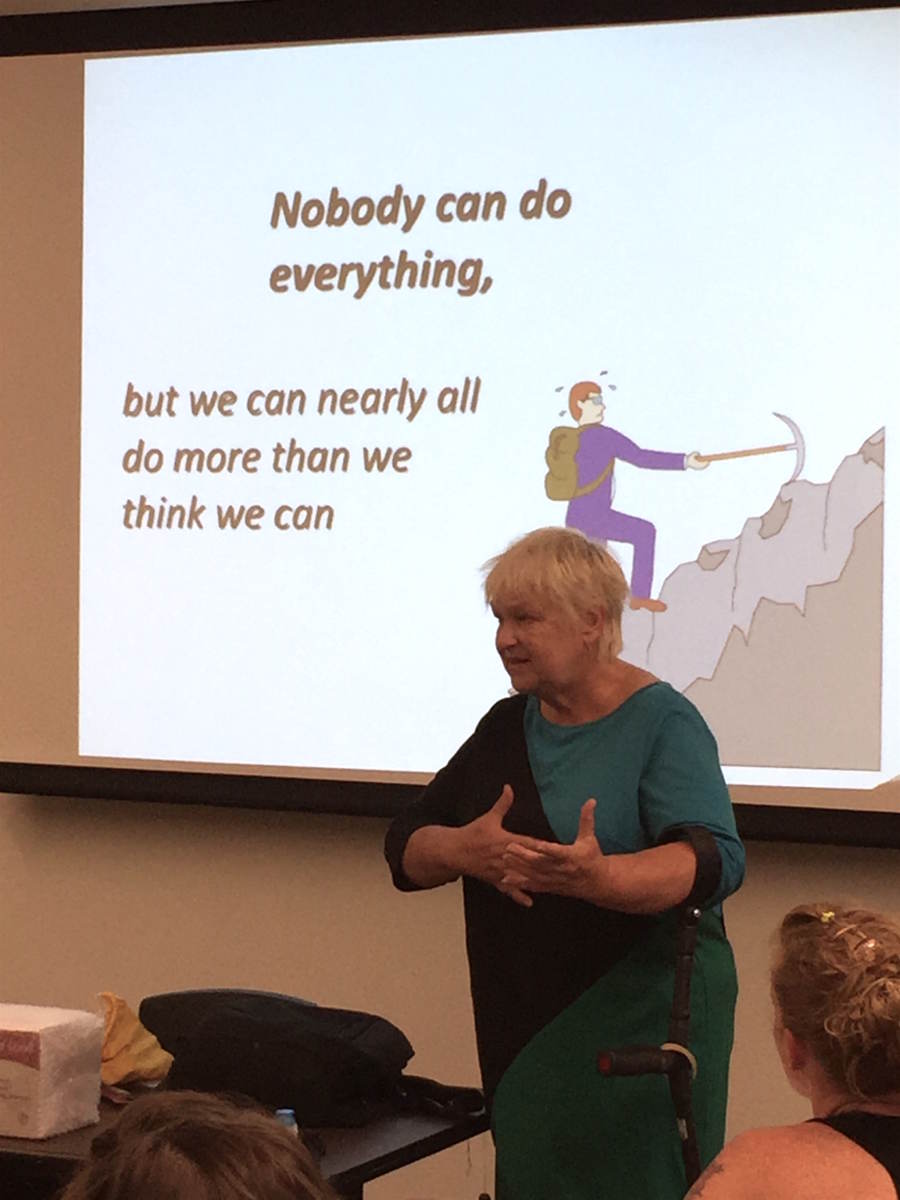

Schnieders is in her 60s and could easily be a mother or even grandmother to each of these women. And she plays the part, approaching her lecture on psychologist Abraham Maslow’s theory about human motivation more like she’s talking to these women over a cup of coffee rather than across a classroom.

Standing in front of a screen where she’s projected a slide about Maslow’s theory, Schnieders begins.

“So, the self. Who are we?” she asks.

“We’re striving toward the potential who we can be,” she said. “What are the roadblocks that get thrown in our way that keep us from getting to that potential?”

After about half an hour of discussing Maslow’s theory, Schnieders drops into her presentation something different: A “little trick,” as she calls it, on how to be a good student.

If other professors “spend as much time on a slide as I just did on these two, chances are it’s going to show up on a quiz or a test. They beat it to death because they think it’s important.”

The women nod their heads.

Later, during a break, most of the mothers head over to the campus “Early Care and Education Center,” a cheerful set of classrooms decorated in primary colors and toddlers’ artwork and filled with Lilliputian furniture that’s sized to fit small people, not their parents or teachers. This is where the mothers’ children are being cared for while they study with Schnieders.

“The support system here is amazing,” Monique Morin said. “I’ve got Lori Joy (a career advisor who assists with the class) texting me every day making sure that we’re doing all of our stuff — you can text the teachers whenever you want.”

The program, said Morin, who has a four-year-old daughter, “gets you prepared for college. It completely gives you a good vibe. Like we’re all single moms in this program, so for them to allow us to bring our children, to have class with us and everything else, it kind of opens the door to us getting used to college.”

An ‘economic imperative’

In a tiny, portable classroom building in Skowhegan, a determined group of people are trying to make future college students out of one-, two- and three-year-olds.

The program housed in this building is an offshoot of a project called “Educare” that first opened in Waterville in 2010. The aim of both is to offer not only high-quality early childhood education, but also to work with parents and families to help them get the government aid and other resources — including child care tuition — that can help them do more than just survive.

There are currently sixteen children enrolled in the Skowhegan program, which opened in September 2015.

“There’s research that shows that children that come from high-risk factors have lower scores across the board; we’re hoping to catch these children up,” said Nicole Chaplin, who runs the Skowhegan program.

But along with teachers, the center employs Jessica Brown, in a position called a “family service coordinator.” The coordinator works with parents to help them understand everything from government child care subsidies to how to find low-cost housing “so they don’t get frustrated and give up.”

The obvious heart of the program are the two classrooms, open to each other, where there are sometimes as many teachers as children.

Early in the morning, the teachers feed children breakfast, an opportunity — as the children put cereal on the floor, in their noses, on their clothes and occasionally in their mouths — to work on their hand-eye coordination as well as manners. They read and sing to the children, help them play with blocks and balls, talk with even the smallest ones about emotions — “Is your baby happy?” the teacher asks a toddler who is cuddling and rocking a doll — and help them solve problems when they get frustrated.

It’s this kind of attention, informed by theory about child development, that has led to an unusual alliance between Maine businesses and the center.

One of the businessmen leading that alliance is Jim Clair, former CEO of a major health care company who previously held a number of top finance positions in state government.

In 2008, Clair and other business executives were invited by Gov. John Baldacci to serve on a committee looking at the importance of early childhood education.

“Prior to maybe seven or eight years ago, I didn’t really know much about the early childhood investment issue,” said Clair. “I was just a guy running a business, just your typical guy.”

That’s when it began to dawn on him that the problems of children in poverty — a significant portion of whom had single mothers — could eventually become the problems of the state’s businesses.

“For us it was at least as much an economic imperative as it was a social imperative,” said Clair. “We own, co-own or run significant companies in the state and we’re looking at this … timeframe where we need to have the type of workers who are able to do the work in this knowledge-based economy, the kind of workers that were ready to learn, willing to continue to learn, could work in groups competently and were technically proficient.

“In 1966, you could leave the high school, get a job in the mill,” he continued. “But those jobs are gone.”

So Clair joined with a group of other executives to found the Maine Early Learning Investment Group. Its goal is to make it clear to business executives across the state that by supporting high-quality early childhood education, they are ultimately supporting the development of the workforce they’re going to need in the future.

In 2015, the business group launched a campaign to raise $1.4 million to support the Skowhegan program and its goal of educating children so they are ready to learn once they reach kindergarten. They’ve raised $875,000 so far.

“If Maine doesn’t deal with this deliberately and successfully, we’re going to see an acceleration of the issues that are going on,” Clair said. “The pockets that are struggling are going to simply get larger and the families that can’t get out of poverty are going to grow, and the people that need public assistance, including special ed, are going to grow. So, therefore, the demand on state taxes and property taxes are going to grow.

“Or,” said Clair, “we can start making some wise investments now that can bend the curve and allow children to have a successful (ages) one, two, three or four so that in kindergarten, they will be ready to learn and ultimately be significant economic contributors and stay in Maine if they want.”

Where’s the political courage?

In Machias, in Washington D.C., in western Maine, there are efforts to answer the powerful question Sawhill asked in “Generation Unbound,” her groundbreaking study of single parents: “How can we do right by children who do not get to pick their parents or the circumstances of their births?”

For those trying to help those children, the answer lies in both helping them and their parents.

But Sawhill warned that the modest efforts underway won’t grow to help the millions of poor single parents and their children unless there is also more candid public discussion of the problem.

But that will take something she and others say is in short supply.

“I’m not seeing very much political courage,” she said. “I’m seeing very little, in fact.”

Reporting for this story was supported by grants from the Samuel L. Cohen, Hudson and Maine Health Access foundations. Demographic analysis was provided by Andrew Schaefer, Vulnerable Families Research Scientist, Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire.

This is part five of a five-part series. To read more about what went into the reporting of this story, click here.