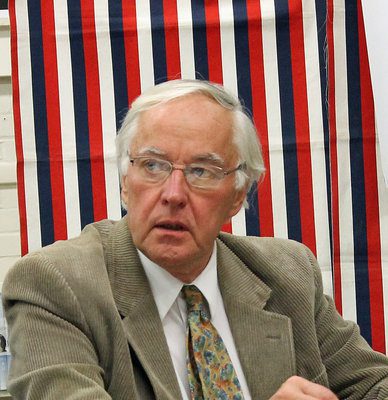

Just as state Rep. John Martin, one of the most powerful Maine politicians of the last three decades, is emerging from the bankruptcy of the convenience store he co-owns, along comes another financial problem.

And this one has a new wrinkle – this time the back debt is to a government agency.

The Northern Maine Development Commission, which is funded by the federal, state and local governments, says that Martin and a partner have failed to pay back $232,000 in loans and interest for their Eagle Lake restaurant and bar, called Tamarack Inn. The commission has asked a judge to foreclose on property Martin and his partner pledged as collateral.

The bankruptcy and the potential foreclosure echo some of Martin’s earlier business dealings.

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting examination of public records shows, for example, that in 2000 a court found Martin in default for another state-funded loan. At the time he was a member of the state Senate.

The records also reveal numerous instances of Martin making late tax payments to government agencies.

The 71-year-old Martin, a Democrat, was defeated two weeks ago by his Republican opponent — a shock to Maine’s political establishment.

Martin served 46 years in the House and Senate, including an unprecedented 10 terms as speaker of the house, and his hold on power was considered the impetus for voters approving term limits in 1993.

Martin has not ruled out running in future elections and has said he will continue to be involved in state politics.

He told the AP his loss was due to negative advertising by the Republican Party. But residents in his district told the Portland Press Herald that news coverage by the Bangor Daily News and the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting of the bankruptcy played a part in voters turning on him.

A federal bankruptcy court recently allowed Martin and a partner to buy back their Eagle Lake store for $125,000, even though they owed about $300,000 to a variety of creditors. The court is still considering which creditors will be paid and how much.

Meanwhile, Martin isn’t without a job in state government: He is assistant professor of political science and executive assistant to the president at the University of Maine at Fort Kent.

In an email to the Center, Martin defended his business record:

“I’ve been involved in helping to create 35 companies and putting people to work in Aroostook County. Some of these have been successful and others have not, regardless, I have always paid my debt and tried to do what is best for my community. Just like so many other businesses across the state, during the last five years, we’ve faced serious financial challenges. My role as a public official is completely separate.”

‘Breach’ of loan terms

On July 12, the Northern Maine Development Commission filed a complaint for foreclosure with the Superior Court in Aroostook County, amended two weeks later. The agency said Martin and a business partner owe the commission $232,000 in unpaid loans and interest and asked a judge to order foreclosures and sales of the restaurant and a nearby property owned by Martin.

Martin and Timmy Soucie formed Tamarack Hill Inc., which owns the restaurant, in 2008. In court documents, the commission claimed that both Martin and Soucie took out commercial loans for the business in 2008, 2009 and 2010.

Martin and Soucie each provided personal guarantees for the loans. Martin secured his guarantee with mortgages on property he owns in Eagle Lake, including the old Post Office Building. The Tamarack Inn restaurant site, 3346 Aroostook Road, was also used as collateral by the partners for some of the loans.

Duane P. Walton, director of business finance for the commission, said, “We had to foreclose because they’re not making the payments. They left us no choice but to proceed with foreclosure.”

In a response filed with the court, Martin and Soucie deny that they are in default.

The commission asked the court to allow the foreclosure and sale to go ahead without a trial “on the grounds that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact.” Martin and Soucie have not yet responded to that filing, except to request more time to answer.

In an email to the Center, Martin said he and his partner “will be current within the next three weeks” with the loan payments.

Soucie said, “I don’t have any comment.”

The money for the Tamarack Hill loans came from two programs, one funded by the U. S. Department of Agriculture and the other by the Finance Authority of Maine (FAME).

The Commission loaned Martin the money and allowed Martin to provide loan guarantees, despite Martin’s default on a previous loan guarantee he’d made to FAME in 1999.

Walton said the commission was unaware of the FAME loan.

He said the commission’s loan officers “take in any information we can find” and run credit reports on applicants, but that process did not turn up the 1999 FAME loan default.

Walton defended the loan to Martin and Soucie.

“We knew of Mr. Martin. We didn’t know Mr. Soucie very well, but between the two of them we had the collateral to back it up and we felt pretty secure.”

Was it a bad loan?

“No, I don’t think so,” Walton said. “I don’t expect to lose any money on this, I can tell you that.”

FAME loan in default

FAME was founded by the legislature in 1983 to help businesses with loan guarantees, tax breaks and bond financing. Funded partially through the state budget, FAME’s board and executive director are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the legislature.

The FAME case involved the Rock Lumber Company, a cedar mill in Portage Lake incorporated by Marcel Theriault and for which Martin served as corporate clerk between 1990 and 2000.

In February and March of 1999, according to court documents, the lumber company took out two loans from FAME’s “Economic Recovery Loan Program” worth $301,000. The loans were guaranteed by both Theriault and Martin. While Theriault guaranteed the entire loan amount, Martin’s guarantee covered only five percent.

In February 2000, FAME filed a complaint with Kennebec County Superior Court stating that Rock Lumber had defaulted on the loans. The guarantors of the loan – Theriault and Martin – were obligated to pay the loans when Rock Lumber did not. Since they did not pay off the loans, they, too, were in default.

FAME said that Theriault owed $327,931, plus attorneys’ fees and costs; Martin owed $16,395 plus attorneys’ fees and costs, according to an affidavit sworn by a FAME official on Feb. 28, 2000.

FAME won its case – no defense was mounted by Rock Lumber, Theriault or Martin.

In July, 2002, the court issued a “writ of execution” against Martin, directing county sheriffs to collect “the goods, chattels, or lands of the Debtor to be paid and satisfied to the Creditor in the sum of $21,993.” The amount represented loan principal, late fines and attorneys’ fees as calculated two years after the FAME affidavit.

Judgment against Theriault was stayed at the time because of a concurrent bankruptcy filing.

In December, 2002 – nearly two years after FAME went to court to gets its money – Martin paid FAME $20,000, although his total debt at the time was $21,993.

FAME spokesman Bill Norbert said, “It just was agreed to. We did pretty well, the agency did. It’s close to the total amount he owed, and it’s not unusual to come to some sort of agreement.”

Martin said, “I’ve repaid the portion of the loan I was responsible for to the bank and the government.”

Martin said he was given a five percent ownership of the company “in exchange for having helped set up the company,” but had no management role. He said he was the corporate clerk and in that role he filed the annual report to the state Secretary of State.

Norbert said that except for another $4,468 from Theriault, the balance of the loans plus interest – around $300,000 — was never paid.

“We do write off some loans,” he said, explaining that FAME “is in the business of taking some sort of risk that traditional lenders don’t.”

Theriault declined to comment, except to say, “That’s past history.”

Would Martin’s problems with the first loans be taken into consideration if he applied for another loan? Norbert said, “I would think so.”

Late tax payments

Martin also has a history of making late payments to government agencies for taxes.

Records from Northern Aroostook Registry of Deeds and the Bald Eagle convenience store bankruptcy case showed the following:

Martin has been late paying his property taxes on a number of Eagle Lake parcels over a period of many years.

Tax records show that liens were placed on Martin-owned properties in Eagle Lake in mid-2003, 2004, 2005, 2009 and four times in 2012.

In August, 2002, Maine Revenue Services placed a lien on Moose Point Camps, owned by Martin and a group of partners, for $1169 in “delinquent” withholding taxes from 2001. That lien was released by the state in August, 2003.

In May, 2004, the Maine Department of Labor placed a lien on Moose Point Camps for unpaid taxes of $304 from the fourth quarter of 2003. The lien was discharged in July of 2007.

The Internal Revenue Service in February, 2005 placed a federal tax lien for $5,340 on the Moose Point Camps. The lien was for unpaid withholding taxes from 2003. It was released in April, 2005.

In his recent bankruptcy filing, Martin and his partner in the Bald Eagle convenience store in Eagle Lake listed a debt to the IRS $4,456 in unpaid withholding taxes from the last three months of 2011, and the Maine Revenue Services $1675 in unpaid sales taxes from December, 2011. The state lien was released halfway through the bankruptcy proceeding.

And in 2010 the Maine Revenue Services also placed a lien on Martin for $3,116 in unpaid sales taxes from the first half of 2009.

Martin said, “I have paid or been paying off all the taxes for the properties I own, I have no knowledge of any unpaid liens on me. Eagle Lake reports all liens and taxes due in the town report. I personally have never been in the town report for outstanding debts – liens or taxes.”